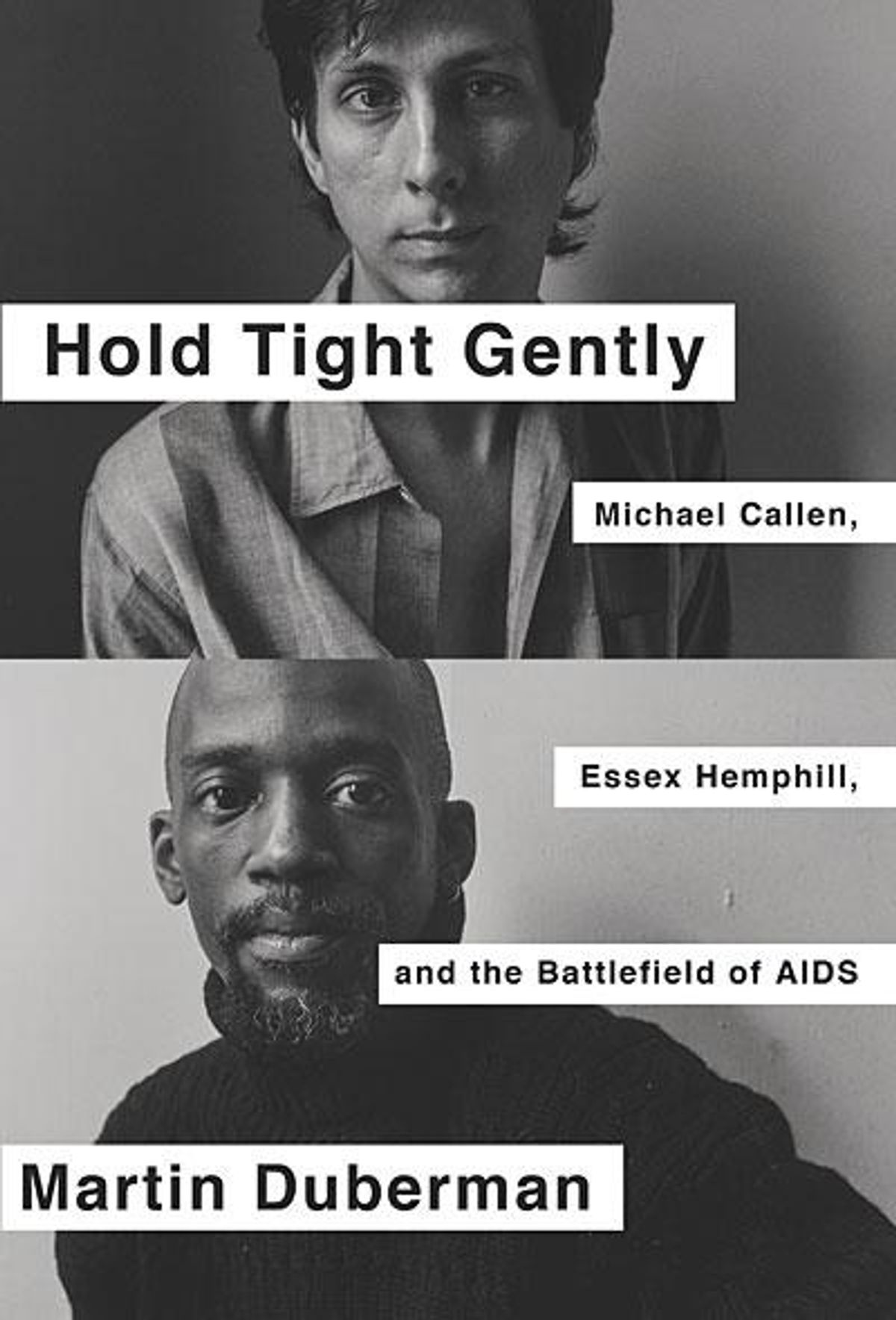

From award-winning historian and activist Martin Duberman comes the poignant new dual biography of two men central to activism in the early days of the AIDS epidemic, Hold Tight Gently: Michael Callen, Essex Hemphill, and the Battlefield of AIDS. Callen and Hemphill were both diagnosed with AIDS and raised awareness of the epidemic long before the rest of the nation becoming aware of the disease’s existence. The year 1995 saw the release of protease inhibitors, the first effective treatment for AIDS, but it was also the year Essex Hemphill, an African American poet and performance artist, died from complications related to the disease. Michael Callen, a singer, songwriter and pioneering AIDS activist from the Midwest, had already passed away two years earlier. Here's an excerpt from Duberman's moving biography of the men and the times in which they lived.

From Hold Tight Gently:

At all times — who can predict a street encounter? — Mike carried with him a jar of lube, 25-cent packets of K-Y to ease entry, a bottle of poppers (amyl nitrate, which produced a disinhibiting rush), two (before and after) five-hundred-milligram pills of tetracycline as anti-STD prophylaxis, and Handi Wipes for the cleanup. Though Mike hardly resembled the muscled gym-built physique then coming into fashion, he had no trouble attracting partners. He was delicately, willowly, handsome: six feet tall, olive skinned, green eyed, and thin (around 135 pounds), with naturally curly dark brown hair — through the right kind of spectacles, something on the order of a Renaissance cherub (minus the wings). Mike wasn’t interested in most of the “extreme” sexual practices then in vogue (fist fucking, water sports, scat, or S/M). His single-minded focus was on getting fucked. When he totted up his sexual scorecard in 1982, at age 27, he figured that since coming out, he’d been “penetrated by an average of 3 men once every 3 days.” Deducting for sick days, that put him in gold medal contention with a total of 2,496 partners, of whom he professed to know the first names of no more than a hundred.

Biographer Martin Duberman (right)

He was outspoken and unashamed about his “sluthood.” Not every fuck had been magical, but the vast majority, he insisted, had given him pleasure. And what, he wanted to know, was wrong with that? No coercion had been involved, no pederasty, no exchange of cash, no pretense at faithfulness or romance. Like other gay male sex radicals of the day, Mike denounced the puritanical fuzziness that sanctioned multiple monogamous orgasms in order to produce children but frowned on a comparable number with multiple partners to produce pleasure. He did “not accept the concept of sexual addiction at all.” A bit later, after he’d become a spokesperson for a segment of the People with AIDS (PWAs) movement, he’d read his sexual history somewhat differently, referring to his generation of sexual liberationists as “predatory, shame-based, dark, use-once-and-throw-away, no contact sex — [all of which went] deep into our wiring.” Later still — in part as a result of reading books by “sex-positive” feminists — he’d reclaim and celebrate his “slut” years.

There was one hitch: the escalating number of STDs. Mike was in and out of [Dr. Joseph] Sonnabend’s office so often that they eventually shifted to a first-name basis. Mike was fond of saying that “if it isn’t fatal, it’s no big deal,” but Joe was less nonchalant about his multiple, incessant infections. When Mike contracted hepatitis for the third time and developed fevers, night sweats, and bloody diarrhea, Joe hospitalized him. Consommé and a battery of tests were his diet for a week. His acne and hemorrhoids improved but a firm diagnosis remained elusive. Sonnabend called in a tropical disease specialist, but the best he could come up with was “atypical malaria.” Mike had never been to the tropics, and the paracytology tests failed to confirm that diagnosis or any other. The doctors were back to where they began — scratching their heads.

Above: Michael Callen at the Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, 1988 (photo by Jane Rosett)

And not just those in New York. The appearance of other, seemingly anomalous symptoms among young gay men was beginning to puzzle physicians elsewhere. The most perplexing were Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), typically associated with the suppression of the immune system; and the appearance of purplish spots on the skin. Sonnabend was among the first to recognize that the spots were indicative of lymphatic tumors, a rare cancer known as Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) that was traditionally associated with elderly men of Mediterranean origin. Mystified, doctors began to compare notes with colleagues around the country.

Washington, D.C., in 1973 became the first large U.S. city officially to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing, employment, and public accommodations. The catch, of course, was that black and Latino/a gay men and lesbians still remained subject to the prevailing racist mind-set among whites — and the prevailing homophobia among heterosexual people of color. It’s possible to argue — though the argument is far from conclusive — that within gay circles discrimination against blacks and Latinos was less pronounced in D.C. than within straight ones.

During a three-day conference at the University of Houston to plan for the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, for example, the organizers set aside 25 percent of all leadership and policy positions for Third World delegates, and the black D.C. Coalition, led by Billy Jones, actively participated. The day before the march, the conference agenda included three panels on racial issues, and both Marion Barry and the well-known writer Audre Lorde spoke at the event itself. Judging by numbers alone — estimates vary but are generally upwards of 150,000 attendees — the march was counted a great success.

Above: Essex, 1991 (photo by Jim Marks)

Yet as Essex and other black gay people well knew, social and cultural circles in D.C. were mostly divided along racial grounds. One of the best-known hangouts for black gay artists was (Valerie) Papaya Mann’s brownstone in Northeast D.C. — a salon-like setting reminiscent of 1920s Harlem Renaissance gathering spots in New York City, of which A’Lelia Walker’s and Carl Van Vechten’s were probably the most famous. Papaya herself had come out in the mid '70s and immediately gotten involved in D.C. lesbian and gay life, organizing a variety of social events and becoming a central figure in Sapphire Sapphos, Washington’s first organization for African American lesbians. It was at Papaya’s that Essex first met his future good friends Chris Prince and Garth Tate and then, through them, any number of other black gay singers, writers, painters, and filmmakers.

One of the early (1979–80) products of these gatherings was the publication of the short-lived but handsomely produced bimonthly Nethula Journal of Contemporary Literature (the name “Nethula” had come to Essex in a dream). He co-founded Nethula with two young women, Kathy Anderson, whom he’d known at the University of Maryland, and Cynthia Lou Williams. Essex served not only as the journal’s publisher, but also as its graphic designer — he’d learned offset printing and typesetting at one of his part-time jobs, and showed a striking gift for it. With wonderful paper stock, stunning cover design, and challenging content, both poetry and prose, Nethula was a state-of-the-art publication devoted largely to the work of the newest generation of black artists. Both Sterling Brown and E. Ethelbert Miller of the older group of black writers were among the journal’s five contributing editors. Miller especially — a poet on staff at the Howard University library — served as an important bridge between the generations.

Poster from an early Hemphill gig at D.C. space (courtesy of Michelle Parkerson)

In 1980, Miller arranged for Essex and the black lesbian poet and filmmaker Michelle Parkerson to share a bill together at the citywide Ascension Poetry Reading Series at Howard University’s Founders Library, which Miller coordinated. Michelle had graduated from Temple University, was then working at the local NBC television affiliate, and had just completed her first film, But Then, She’s Betty Carter. The two had never met before and the connection proved immediate and consequential for both. As Michelle recalls the evening of their joint reading, “I was just struck by this young brother, whose poems were incredible . . . beautifully sensual and homoerotically brave, which was right where I was at with my own work.” After the event concluded, Michelle approached Essex: “Hey, where you been all my life?” she laughingly asked, and told him how much she loved his work. Essex felt the same about hers and the two became fast friends.

See more images on the following pages >>>

Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen writing How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, New York, 1983 (photo courtesy of Richard Dworkin)

The first safe-sex poster, 1983

Richard Dworkin and Michael Callen, 1988 (photo courtesy of Richard Dworkin)

Essex Hemphill at the San Francisco Out/Write Conference, 1991 (photo by Lynda Koolish)

Hyde Street Studios, San Francisco, June 1993, rehearsing for the Legacy album—left to right: Michael Callen, Chris Williamson, and Holly Near (photo by Patrick Kelly)

Essex the poet, 1985 (photo by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks)