The weekend after the Supreme Court ruled in favor of nationwide marriage equality, Julian Walker marched in San Francisco’s LGBT Pride parade. The 22-year-old gay actor is star of the indie hit Blackbird, director Patrik-Ian Polk’s new film based on Larry Duplechan’s iconic novel about a gay Christian teen coming of age in a zealously religious Mississippi town, which has recently been released on DVD. Walker was at San Francisco Pride with a costar of the film, singer-dancer-actor D. Woods, to perform on the Soul Stage. It was his first LGBT Pride and it was exhilarating.

“The experience was absolutely amazing,” Walker says of the event, which drew a jubilant crowd of over 1 million people, many there also celebrating the historic Supreme Court decision, Obergefell v. Hodges, that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. “It was just so beautiful to see so many people out there happy and celebrating. It wasn’t even just gay and lesbian people out there. There were straight people with their family and friends. Everyone came together for one purpose, which was love.”

Pride and self-acceptance are sentiments that Walker’s character, Randy, experiences precious little of throughout the majority of Blackbird. A high school student in Hattiesburg, Miss., Randy struggles with the shame he feels about his attraction to other men. Leaders in his black church, where he sings in the choir, as well as his devout mother, played by Mo’Nique, stoke the stigma — sometimes unwittingly — that surrounds his (secret) sexual orientation.

Oscar-winner Mo’Nique (here with Julian Walker) says homophobia is destroying black lives. “It’s time for us to say, ‘Let’s make it a better place and accept people for who they were made to be.’ ”

Sadly, Randy’s experience is one that is still alarmingly common among African-American teens and young adults in America. Black gay and bisexual men, who already weather the socioeconomic hardships of racism and mass incarceration, are particularly vulnerable to the stigma of homophobia. Many are left to battle discrimination and homophobia without traditional support networks like church, family, and community, and the result, experts say, is the perfect storm for a health crisis.

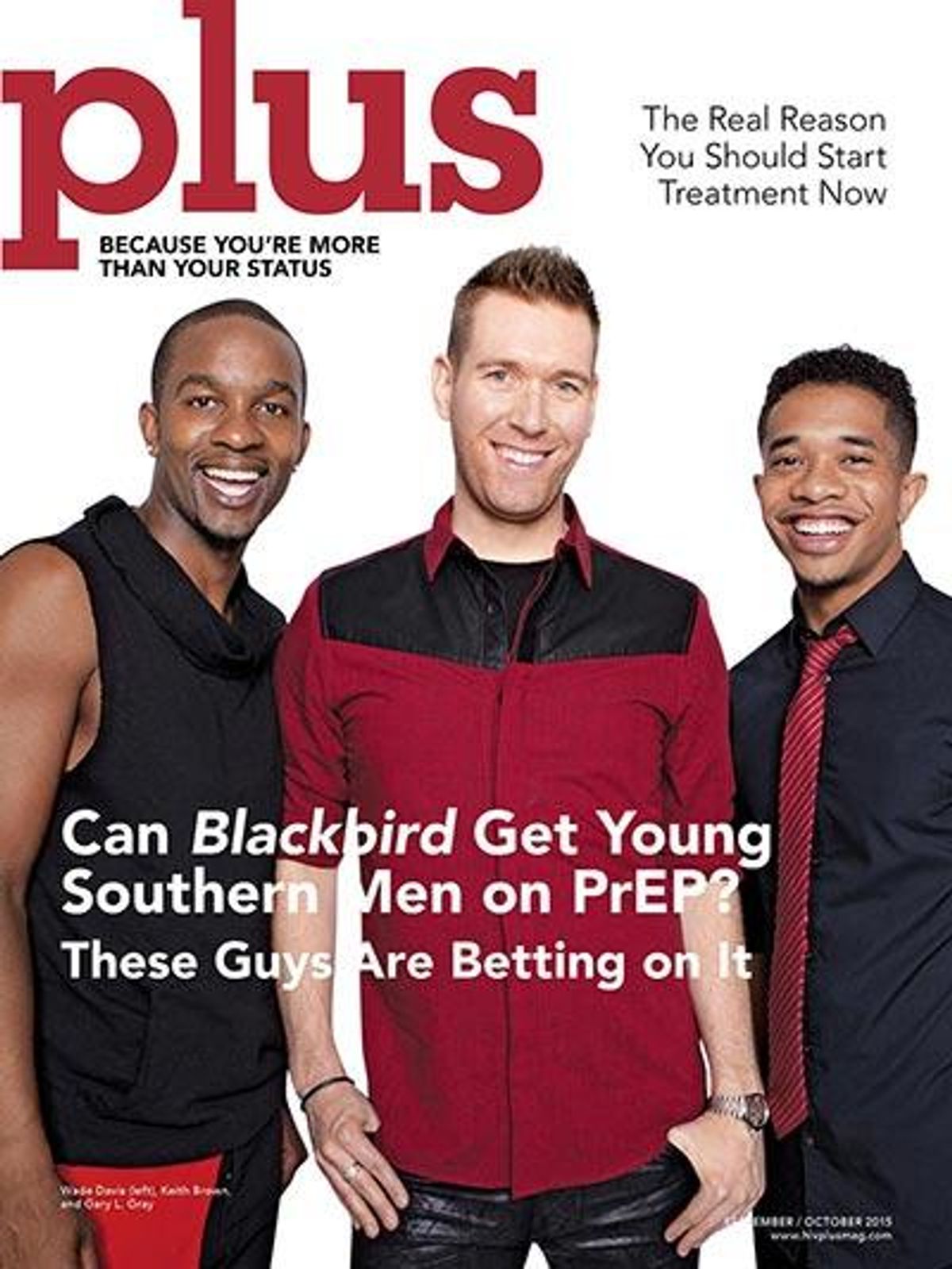

At left: Blackbird producer Keith Brown

At left: Blackbird producer Keith Brown

Young gay and bisexual African-American men bear the terrible brunt of the HIV epidemic today. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that this group has more than twice the rate of new HIV infections as white or Latino men in the same age range. At the current rate of HIV infection, a black gay or bi man has a 60 percent chance of being HIV-positive by the time he turns 40.

As a young black gay man, Walker finds that statistic terrifying. “That’s scary,” he says, then pauses. “That’s really scary.”

Despite stereotypes, this epidemic is not limited to gay and bisexual men. Though African-Americans make up only 12 percent of the U.S. population, they account for nearly half of new HIV infections. The rate of new infections among African-American women is 20 times that of white women. An estimated 56 percent of black transgender women are HIV-positive.

Racism, poverty, and homophobia are key factors in this epidemic. And their mixture is volatile. Many black communities already lack essential resources like education and health care, and the stigma attached to being LGBT or having HIV prevents many from getting tested, using HIV prevention methods, getting treatment for HIV after testing positive, and accessing health care resources overall.

Studies also show that for a variety of reasons, black gay men are most likely to date other black men, which ultimately increases the likelihood of HIV transmission because of the overall high rate of HIV within the population.

So how does society even begin to address such entrenched problems? One major tool is media. Blackbird is an ambitious and far-reaching film, insofar as it takes on issues that few, if any, other Hollywood projects are tackling. Homophobia among African-Americans, the so-called down-low culture, interracial relationships, abortion, the hypocrisy of religious leaders, and the plight of missing black children are among the hot-button issues addressed.

At right: Gary LeRoi Gray

At right: Gary LeRoi Gray

It also travels where few other films have dared: to the health clinic, where Randy’s best friend, Efrem (played by Gary LeRoi Gray), gets an STD screening — and yes, an HIV test — after a risky encounter in a midnight cruising spot leaves him with a strange rash on his genitals.

The purpose, Walker says, is to send a clear message to the audience: “Go get tested and continue to have safe sex. You have to protect yourself, because you never know what may happen.”

Gray, a 30-year-old straight actor and rapper who first rose to fame as a child actor on The Cosby Show and as an in-demand voice actor, has played a gay man before. He had a pivotal role in the film Noah’s Arc: Jumping the Broom, based on the popular black gay TV series created by Blackbird director Polk. Still, he says, he learned much from his experience on Blackbird. The film, he says, takes a strong stand against “the fear that comes along with coming out, being free,” the same fear that “causes things like health to be overlooked in many cases.”

Gray also thinks it’s important to remember that “HIV is not just a gay issue, it is an issue.” Even though it’s disproportionately hitting African-American gay and bi men and trans women, “any health concern this big cannot continue to be pushed upon a [single] demographic,” he says.

In a groundbreaking move, the cast and producers of Blackbird are taking this message of HIV prevention and care off of the screen and into the real world. The actors and filmmakers have partnered with AIDS Alabama — a small but mighty statewide organization committed to providing resources like housing and health assistance to those with HIV — to help launch its PrEP Up Alabama program. The initiative will raise awareness of the HIV prevention tools available to gay men of color, including PrEP, the use of a preventive medication, a strategy that has seen little pickup in the South. The PrEP Up Alabama initiative will also help AIDS Alabama reach the at-risk youth demographic with its services.

As part of this partnership, Mo’Nique, who also served as an executive producer of Blackbird, released a video invitation to a screening and Q&A with the cast. Folks who wanted a ticket to the July event at the Birmingham Museum of Art found that the admission price was an HIV test, a marketing tactic that may be the first of its kind for Tinseltown. (It’s been utilized at hip-hop and rap concerts in other states, however.)

“Not only are we asking you to support the film, but also yourself,” Mo’Nique said in a video she released on social media and which quickly went viral. “Get a ticket and get tested. How amazing is that?”

The collaboration continues the mission of what Mo’Nique set out to do with the film’s creation, which was to counter the homophobia she says is destroying the lives of so many people.

“It’s enough,” she says. “It’s enough for us to stop hurting, and hurting one another. It’s time for us to say, ‘Let’s make it a better place and accept people for who they were made to be.’ ”

“I’ve played the video a million times, and I still can’t believe our agency’s name came out of her mouth,” says Dafina Ward, the director of prevention and community partnerships at AIDS Alabama. “It’s pretty amazing. I have so much respect for Mo’Nique and for celebrities who truly utilize their platform to empower others.”

Mo’Nique and executive producer Sydney Hicks at the Outfest screening of Blackbird.

Mo’Nique and executive producer Sydney Hicks at the Outfest screening of Blackbird.

In addition to the Alabama premiere of Blackbird, which was timed just before its August 4 DVD release, PrEP Up Alabama also kicked off a series of community discussions that will raise awareness about pre-exposure prophylaxis, the daily dosage of a pill that some studies have shown to be 99 percent effective in preventing HIV. Funded in part by Gilead Sciences, the new initiative will survey and educate those who are most at risk.

“African-American men are not engaging in PrEP services as much as we would like them to be,” Ward admits, which she attributes in part to a lack of awareness as well as hurdles like employment and health insurance. In many areas, PrEP is available at little to no cost, but most African-Americans don’t know that.

“There’s no reason — no logical reason — for the infection rates of gay black men to still be as high as they are,” adds Blackbird filmmaker Patrik-Ian Polk, whose past projects like Noah’s Arc, Punks, and The Skinny also addressed HIV issues in the black community. “The medical advancements are there…we just need to make them more widely known and more widely available.”

In addition to economic hurdles, stigma against HIV and LGBT people is a force that remains a sizable barrier in prevention in communities like Birmingham. Keith Brown, a producer of Blackbird, immediately recognized what this city has in common with the film’s Mississippi milieu. HIV affects the South more than any other region in the United States — in 2013 it had more than half of the nation’s new HIV diagnoses, according to the CDC, and for a variety of reasons, more of those cases progress to AIDS than in any other part of the country as well. Brown wanted to be a part of the plan for addressing that.

“People don’t want to be seen near the testing center because of the stigma with it,” says Brown of one of the barriers in Birmingham and beyond. He adds that, much like Randy, the young man at the center of Blackbird, many men worry that “they’ll be shunned by their family and friends, and called out” for trying to seek testing and treatment.

Movies can play a big role in changing hearts and minds, says Brown. He says a star like Mo’Nique is a bit like “sugar” on a bran muffin; a little bit of her input sprinkled on certain subjects — like HIV and homophobia — may make them palatable to audiences, inducing some folks to listen to ideas they’d not normally want to consume. Brown doesn’t say it, but the fact that the cast and filmmakers are primarily African-American helps too.

Of the film and its use in HIV awareness, he does say, “It’s such a perfect fit. We’re excited to be involved. We’re hoping, by involving the star power that we have with a film, we can up those numbers and get more people tested than [AIDS Alabama has] been able to in the past.”

At left: Wade Davis

At left: Wade Davis

Of course, this all came about because of an athlete. The man who first connected Blackbird with AIDS Alabama is Wade Davis, a gay former football player and a PrEP Up Alabama ambassador, who led many of the HIV discussions on “Game Changing Weekend” in July. His career as an athlete gives him sway among young men, but his activism background more than qualifies him for the role. Davis is the executive director of the You Can Play Project, which fights homophobia in sports, and he is also a board member for Gay Men’s Health Crisis, one of the country’s largest HIV service organizations.

Davis, “a firm believer that visibility is advocacy,” recognized how black Hollywood could battle stigma with star power.

“Someone of a Mo’Nique stature, to use their platform to have these hard conversations in a very public way? Hopefully, that will spark another person to think that they should educate themselves on the issue,” he says.

While he may not wish to see every actor in Hollywood championing this cause — some celebrities, he points out, are just off-brand for the message — he speaks highly of the value of the “right people who have the right lived experience” in speaking out about HIV.

By “lived experience,” Davis doesn’t mean they need to be HIV-positive or have grown up in a disenfranchised community. They just need a passion for the cause and a drive to educate themselves about the issue. This is the first, crucial step that anyone can take to help fight daunting battles against HIV, poverty, and racism.

“It’s really hard for someone to be thoughtful about something they’ve never thought about,” Davis says. Armed with this knowledge, a person can make an active choice to have conversations with

people in their daily lives about this issue and “be fearless” in doing so. This will inspire others to do the same.

“Start to imagine a world that is outside your own mirror,” Davis says. “Oftentimes, people focus on things that only impact them.” Once they step outside this comfort zone, he says, people can realize, “Wow, we are really all a part of this together.”

This lesson could be particularly valuable to LGBT people in the aftermath of the marriage equality movement. That fight united many organizations and individuals, including major civil rights groups, in a common cause, and its seeming speed led to a realization of what could be done through collaboration. The marriage equality win has left many searching for the next battle and wondering how such success could be replicated.

“Marriage is a great thing, but it is a privileged idea,” Davis says. He points out that young black gay and bi men have far greater things to worry about — HIV, unemployment, homelessness — before wedding bells become an item on their checklist. The key, he says, is to “connect the dots” between the people who have the money, power, visibility, and access and issues that affect those who don’t necessarily look like that person in the mirror.

“We have to stop being so damn afraid to see ourselves in everyone else,” he says. “When we as a country can get to that point, we will actually genuinely care about each other. In order to end this epidemic in communities of color, it’s going to take all of us — black and white, male and female, gay and straight.”

AIDS Alabama’s Ward agrees. She points out that the lion’s share of HIV work is shouldered by LGBT organizations, at a time when a variety of groups should be working in tandem to create change.

“The torch should not have to be carried solely by the LGBT community,” she says. “It’s a social justice issue. It’s an issue of classism and access and so many other things.”

She says stars like Gray, Walker, and Mo’Nique help push these ideas into the mainstream.

“Celebrities need to be more engaged in having these conversations,” she adds. “We can’t decide that we only care about certain people’s lives. And that’s been part of the problem.”

But Wade Davis and the rest of the Blackbird team certainly aren’t alone in the fight against HIV. Broadway star Sheryl Lee Ralph has been educating audiences about HIV with her one-woman show for years. Rihanna was the 2014 spokeswoman for Viva Glam, a makeup line that contributes proceeds to the MAC AIDS Fund. Alicia Keys has become one of the most visible musicians talking about HIV among women. Actors like Dennis Haysbert, Alimi Ballard, Jason George, Nadine Ellis, and Jussie Smollett are all voices for Greater Than AIDS, an organization that works to raise awareness of HIV issues in at-risk communities.

Smollett (above), the star of the Fox smash hit Empire, has been an HIV activist for all of his adult life, he says. In a recent panel at New Orleans’s Essence Festival called “The Power of Love and Family,” the gay actor revealed a crucial conversation about HIV he had with his mother when he was about 10 years old. The discussion occurred after a crew member to whom the young Smollett had grown attached while filming a television show died of an AIDS-related illness.

Smollett (above), the star of the Fox smash hit Empire, has been an HIV activist for all of his adult life, he says. In a recent panel at New Orleans’s Essence Festival called “The Power of Love and Family,” the gay actor revealed a crucial conversation about HIV he had with his mother when he was about 10 years old. The discussion occurred after a crew member to whom the young Smollett had grown attached while filming a television show died of an AIDS-related illness.

“It is a parent’s duty” to educate their child about HIV and testing, Smollett stressed, before it’s too late to have that conversation. He compared the stigma of having such talks to letting kids outside in a snowstorm without a shirt.

This is a sentiment echoed by both Davis and Polk, who in their interviews with Plus said they never had such a conversation with their parents growing up. Such silence, if it continues, will only prolong the HIV epidemic, they say.

“Parents have to actively engage in the lives of their gay children, underage or adult,” Polk says, or they risk them obtaining misinformation about sexual health that will put them in danger.

Moreover, Smollett believes that it is a celebrity’s duty to use their platform to enact positive change. This was another lesson imparted by his mother, who gave him and his siblings “no choice whether we were activists or not. If millions of people are listening, shouldn’t you say something that’s worth hearing?”

“I’m 30 years old, and I’ve never lived in a world that was free of HIV and AIDS,” he said with sadness during the panel. But he also emphasized that the world has all the tools needed to eliminate AIDS, something he hopes the next generation will accomplish in their lifetimes.

At the panel, Smollett’s own shirt was printed with “Black Lives Matter: Know Your Status.” This text illustrates how some activists are trying to expand the meaning of the Black Lives Matter movement, which many associate with issues like violence and mass incarceration of black people, to include topics like the disproportionate impact of HIV.

“I believe that Black Lives Matter movement is really about addressing systemic oppression and systemic prejudice,” Ward says. “And I think that HIV is definitely a piece of that.”

Davis adds that the conversation around Black Lives Matter is starting to include the mind’s well-being as well as the “mental scars” developed over a lifetime battling prejudice and stigma. These scars aren’t always visible. Not every assault, he points out, is physical.

“Genocide” is a term employed in the Black Lives Matter movement to describe the state violence and imprisonment targeting black people. It is a term also used by Larry Kramer at the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and again in 2015 to describe how government inaction and public indifference lead to wholly preventable AIDS-related deaths.

“I believe in evil,” Kramer said at a 2015 awards ceremony for Gay Men’s Health Crisis. “I believe evil is an act, intentional or not, of inflicting undeserved harm on others. Genocide is such an act. I believe genocide is being inflicted upon gay people. Genocide is the deliberate and systematic extermination of a national, racial, political, or ethnic group such as gay people, such as people of color.”

The 80-year-old activist adapted his 1985 play The Normal Heart, which chronicled the AIDS epidemic between 1981 and 1984, into an award-winning HBO film in 2014. The project shows the plight of white gay men who fought for their lives against the virus in New York. As communities of color continue to do the same in present day, the world is perhaps well past due for a sequel.

At left: Blackbird producer Keith Brown

At left: Blackbird producer Keith Brown At right: Gary LeRoi Gray

At right: Gary LeRoi Gray Mo’Nique and executive producer Sydney Hicks at the Outfest screening of Blackbird.

Mo’Nique and executive producer Sydney Hicks at the Outfest screening of Blackbird. At left: Wade Davis

At left: Wade Davis Smollett (above), the star of the Fox smash hit Empire, has been an HIV activist for all of his adult life, he says. In a recent panel at New Orleans’s Essence Festival called “The Power of Love and Family,” the gay actor revealed a crucial conversation about HIV he had with his mother when he was about 10 years old. The discussion occurred after a crew member to whom the young Smollett had grown attached while filming a television show died of an AIDS-related illness.

Smollett (above), the star of the Fox smash hit Empire, has been an HIV activist for all of his adult life, he says. In a recent panel at New Orleans’s Essence Festival called “The Power of Love and Family,” the gay actor revealed a crucial conversation about HIV he had with his mother when he was about 10 years old. The discussion occurred after a crew member to whom the young Smollett had grown attached while filming a television show died of an AIDS-related illness.