Let’s face it, anyone in her 60s who is living with HIV can be called a survivor. But Wanda Brendle-Moss is more of a fighter than most.

The Winston-Salem, North Carolina native (who will be “62 years young” in August) has been held up at gunpoint during a home invasion, survived horrific abuse from a man she loved, nearly died of AIDS complications, and survived the death of her stepson (who was murdered by his girlfriend’s estranged husband). She still has three children, two by birth and one by marriage to husband number three, about whom she admits. “He left me for a ‘mutual friend’ and I refused to foot the cost of a divorce.” Brendle-Moss laughs, acknowledging they may still be legally married.

She was 17 and pregnant when forced into her first marriage, and relieved when her abusive husband left while their daughter was still an infant. “My parents knew my husband was abusing me, yet never intervened,” she recalls. That relationship might have primed her for a lifetime of disappointments in love — and the indomitable spirt of an HIV activist.

The day before her daughter's 21st birthday (“she was living with us, pregnant with my first grandchild”), Brendle-Moss was assaulted by a stranger, robbed at gunpoint in her own home. Terrified, and the only one home at the time, Brendle-Moss tried to fend off the robber with whatever she could grab. In this case that was a large boat oar.

“I raised the oar; he raised a gun. Gun trumped the oar,” she admits. “For whatever reasons, I remained calm. I talked to him, I told him I had no money. He walked me into my bedroom, searched drawers and found nothing then he backed me into my daughter's bedroom where she was accumulating things for the birth of Gabriel.”

That’s when her attacker raised the gun, put it against her chest, and pulled back the hammer. “I calmly said, ‘Look around this room. Don't you think if I had anything, I would give it to you? I am expecting a grandson in couple of months. He looked me in the eyes, hit me in the left shoulder, then told me to go back to my bedroom, put me into our closet and told me if I came out he would kill me.”

The soon-to-be grandmother waited for what “seemed an eternity” then slowly stepped out and called police.

Her latest husband left her days later, less than a week shy of their ninth wedding anniversary. Soon she met a new man, a knight in shining armor, she thought, who helped her through the devastation she felt over yet another failed marriage.

Sadly, the armor was tarnished and she experienced worsening violence during that two-year relationship. Towards the end of their relationship, it was “extremely violent, being beaten to point my face looked like ground hamburger.” When she awakened to find him standing over her with a screwdriver and threatening to push it through her eye into her brain, she called her son Andy, who drove all night to come rescue her.

She went to her local battered women's shelter the next day, where the counselors advocated for self-care. Although she'd been a nurse for two decades, Brendle-Moss hadn't seen a doctor despite feeling well during the last few months of that abusive relationship. She was losing weight, getting candidiasis repeatedly in her mouth and throat. When her doctor finally examined her, they talked about the abuse she’d experienced, and ruled out common things like strep throat.

“He put his hand on my knee, looked me in the eye, and said, ‘Let's do the test.’"

She was stunned. "Because — particularly in my region — a Caucasian, heterosexual woman is not expected to become HIV-positive, according the all the propaganda; so despite being a nurse, I never even considered that as a possibility."

With her healthcare experience though she was able to interpret the meaning when "the doctor called me himself and told me I needed to come into the office."

"I just knew I was indeed HIV-positive," Brendle-Moss explains. "I went into the office — this same doctor came in on his day off — and accompanying him was a social worker. He gently confirmed that my test was positive. He explained that he asked the social worker to be there...because he wanted me to sign an agreement stating I would not harm myself and that I would go to the infectious disease clinic appointment that was arranged for me.”

That was 2002, two years after Brendle-Moss had retired from nursing. The last seven years of her career were spent managing patients waiting for (primarily) heart transplants (“It was emotionally draining [work]…especially knowing that someone must die for a heart to become available.”) She had loved nursing, even in the 1980s when many of her fellow nurses refused to care for people dying of AIDS complications. She believed “that every patient was someone's brother, sister, father, [or] mother and I would treat each one as I would want my family treated.”

Learning she herself was HIV-positive would eventually galvanize Brendle-Moss to become a woman to be reckoned with.

After leaving the women’s shelter, she had found a home in rooming houses, but hadn’t returned to nursing. She was working at a restaurant when diagnosed.

“I went to the owner and told him about becoming positive,” she recalls. “He was sympathetic on one hand; on the other he said if I talked about it, he would fire me.”

During a bout of depression in 2008 she went off her meds. That “brilliant idea,” she says facetiously, “led to severe flu. I could not even get out of the recliner to go to bed. I soon noticed this odd feeling in my face, kind of tingly and irritating, then little red bumps appeared.”

A trip to the emergency room confirmed she had trigeminal shingles, as well as a sky high viral load, and almost no CD4 cells. She was admitted to the hospital where she had worked for 13 years and given the diagnosis of AIDS.

“I awoke to find my daughter sitting beside my bed in tears,” Brendle-Moss says, “fearful that I would die, which could have happened if this incident had not woken me up. Since 2008, I have remained on my meds. I quickly returned to an undetectable viral load, but my cd4 was stubborn — it took couple of years for it to get to 225 and even today it has just hit 240.”

She learned through research that the virus reacts differently in women, especially those in midlife. “So I decided I would not focus on numbers. I would focus on how I felt.”

After all of her broken relationships, more than one bout of homelessness, and weeks of living out of her car, a local minister gave her the number to AIDS Care Service (ACS). “Within an hour after her call, two Volvo station wagons pulled up to where I had spent the night and took me to their transitional housing called the HorseShoe.” As she started to heal, slowly building her spirit and her health back up, she decided she wanted to volunteer for ACS and give back. She was told no at first. “It was not allowed until Katherine Foster — the driver of one of the Volvos — became president of ACS. I was the first client to become a volunteer,” she says with plenty of pride.

Because Brendle-Moss was so open about her life, about living with AIDS and having survived both homelessness and intimate partner violence, Foster encouraged her to speak to the media and to remind everyone that the face of HIV can and does need to include straight, white women. As a nurse, Brendle-Moss saw doctors in major hospitals who had wealthy clients come in for treatment “in dead of night so as not to be seen.” She thinks this may work the same way for white women living with HIV. “I suspect the gap between known HIV infections among women of color and white women is that, though I am not in this group, many white women are financially able to have private physicians, afford to pay out of pocket for their HIV meds, and have doctors that do not report their status as required to [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention].”

Once Foster helped Brendle-Moss build up enough confidence, the activist started spreading her message outside of North Carolina. One local organizer, Ryan Eller, who was then with CHANGE (Communities Helping All Neighbors Gain Empowerment) invited her to become a part of the Winston-Salem Homeless Caucus; she became the group’s chairperson in 2011. Soon the city’s mayor, Allen Joines, appointed her to advise on the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Commission that created and implements the Ten-Year Plan to End Chronic Homelessness.

Since 2011, Brendle-Moss has taken leadership training for poz activists, became a social media presence around HIV, volunteered for 10 days at the XIX International AIDS Conference, and talked to legislators in Washington D.C. (part of a two-person North Carolina delegation), encouraging them to support funding for the National Institute of Health to research HIV and aging.

After the International AIDS Conference, Krista Martel of The Well Project invited Brendle-Moss to become one of the A Girl Like Me bloggers.

“I said, ‘But Krista, I am not a young woman.’ And she told me, that’s the point — you can provide a completely different perspective, enabling A Girl Like Me and The Well Project to have a truly diverse representation of women of all ages, races, nationalities.” Since then she’s become active with Positive Women’s Network-U.S.A., a group she says has supported her as well.

In 2013, this nurse-turned-HIV-activist was the sole North Carolinian attending the ADAP Advocacy Association (aaa+) Annual Conference, where she met Brandon Macsata, who Plus magazine named among the “Top 25 LGBT Leaders Fighting HIV/AIDS” in 2009.

“For some reason, he saw something in me,” says Brendle-Moss. “He challenged me in front of everyone to bring six people with me in 2014. I had six, but two got sick and could not attend.” Still she was awarded the Emerging Leader 2014 by aaa+. Macsata continued to challenge the late blooming activist to bring more and more people to the conference. “This year I am I am challenged to bring 10 — and already have 10, barring complications!”

Brendle-Moss also attended her first AIDS Watch in 2014 (“Which was amazing”), where she met Brian Hudjich of HealthHIV and she joined his Pozitively Healthy advocacy group.

That same year, as the Sero Project was planning the inaugural HIV is Not a Crime conference, Brendle-Moss told organizer Tami Haught that North Carolina did not have a criminalization law.

“Oh how much I have learned about how sneaky North Carolina is about criminalizing HIV since then!” she says. When she and her best friend TerL Gleason were invited to an event with the North Carolina Dept. of Health and Human Services HIV Prevention and Care Advocacy Committee (HPCAC), “they immediately asked us to become members as sadly, HIV-positive representation is sorely lacking,” she says. “Our membership was approved in January 2016, so we are now two more positive voices having an impact on all things HIV and hep C related in NC.”

At the event, Brendle-Moss asked what the group’s stance was on HIV criminalization in North Carolina. “The leadership looked at me and said, ‘I am unaware of any issues here.’ I shared with her that I personally am friends with 1 gentleman who, after a bad breakup, the ex when to a district attorney who charged [this man] with some minor offense but added HIV as an aggravating factor — and he served 10 years in prison, lost his job, his home, has to register as a sex offender. The whole room was stunned.”

She and Gleason are heading together to the HIV is Not a Crime 2 Training Academy next month at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. “We have advised our HPCAC, and all other groups we are a part of that we will be reporting back — that we must be a part of the solution!”

Today, Brendle-Moss isn’t the woman she once was as a stressed out nurse in a string of bad relationships. Her activism goes beyond HIV into social justice and she’s proud that today she calls NC NAACP president Reverend William J Barber II and his second in command Reverend Curtis Everette Gatewood friends. She even got her family to return to Oak Island, NC (aka Long Beach), where she spent summers as a child. A family reunion over Easter Weekend brought together Andy, his wife Jenny, and their 5-year-old Russell, along with her daughter Bambi and her husband art who, she adds, “has grown into fine stepdad to my eldest grandchild, Gabriel, who will be 17 in October, and granddaughter who will be 15 in May.”

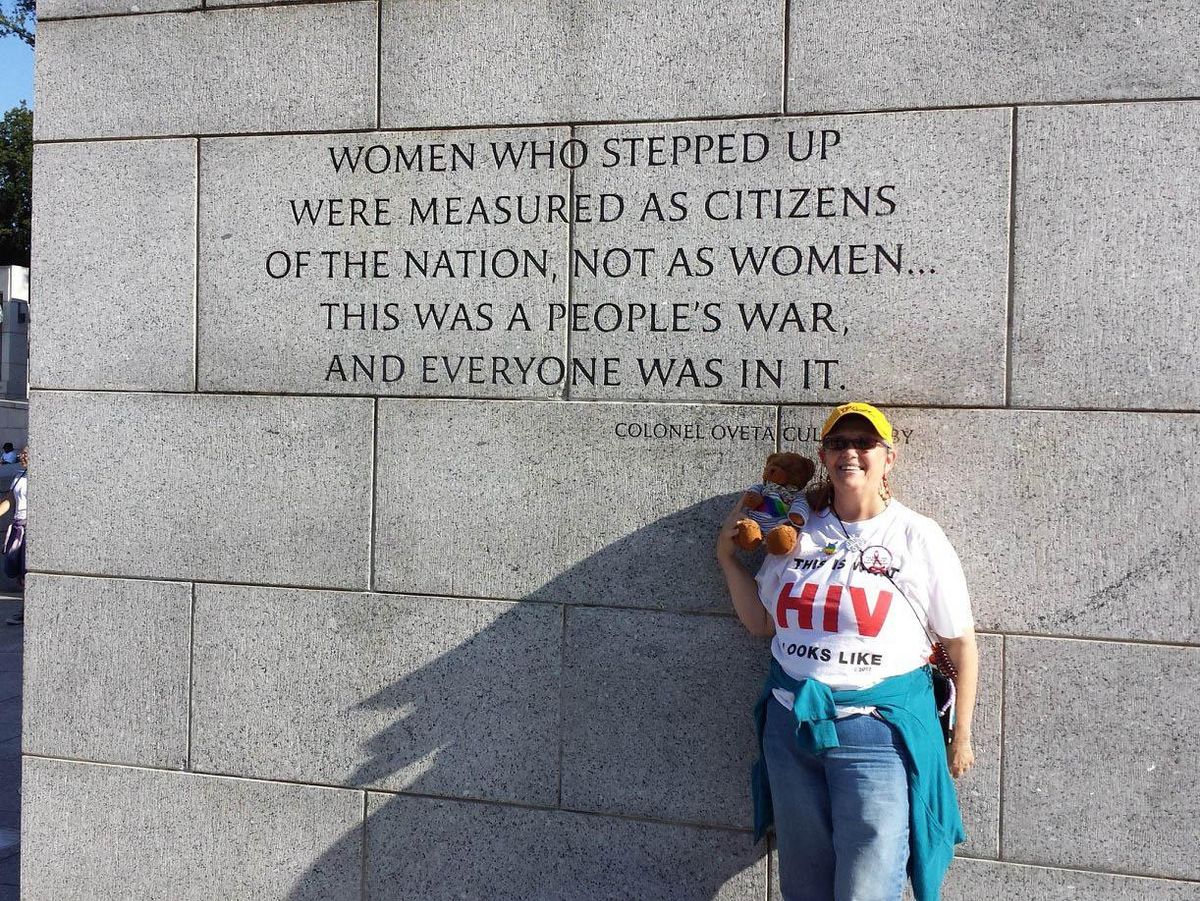

The women of her family at the reunion, with Wanda Brendle-Moss (far right)

Family, friends, a vast social network on and offline. “I have not let having no money or no transportation stand in my way,” she says. “I apply for scholarships, TerL and I tag team. He calls me his ‘social lubricant’ and we are a true dynamic duo!”

Still Brendle-Moss admits that some folks think she’s a bit “weird” because she calls being poz and “living healthily with AIDS a gift. If not for it, no one would have a clue who Wanda is. I would not be speaking at Winston-Salem State University or Wake Forest University on being positive, on sexual responsibility, on intimate partner violence and if not for every bump, bruise, beating, stomping, I would not be me.”

This 62-year-old social activist says she learned years ago that “as long as I felt a victim, I was a victim — and I allowed those who had hurt me ongoing control over my life. When I had that a-ha moment, I set myself free and regained the powerful advocate activist you see before you today.”