The aches and pains of HIV are often overshadowed by concurrent illnesses or concerns about elevated cholesterol, blood sugar, liver enzymes, or blood pressure. Sometimes they are simply considered trivial complaints by a patient or by a physician who feels that the stabilization of HIV by combination therapy is such a godsend that it is inappropriate to complain about sore muscles and aching joints. This dismissal is not acceptable.

An infection like HIV causes the body to produce a host of immune responses — antibodies, white-cell activations, and various circulating immune complexes that attack invading organisms and surrounding tissues. Usually these responses target only infectious organisms, but defenses sometimes lose their specificity and attack normal tissues. And occasionally, defense mechanisms attack tissues without provocation.

These are called collagen-vascular or rheumatologic diseases and are treated by the medical subspecialty rheumatology. In the simplest form, joint aches, called arthralgias, occur in 45 percent of people living with HIV. No clear cause is identified, and treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen or naproxen helps.

People with HIV often think they are getting neuropathy because of the persistent low-grade pain of arthralgias. But the presentation is different. Here it is often the larger joints that ache, compared to neuropathy's onset of pain in the ends of the fingers and toes. The reassuring feature is that these joint aches do not lead to degenerative joint disease or arthritis.

Many viral infections cause a joint to become hot and swollen, and HIV-associated arthritis behaves like the rest. It lasts up to six weeks and gets better with nonsteroidal drugs or steroids like prednisone. HIV-associated reactive arthritis is more involved. Fingers and toes may swell. The Achilles tendon and the plantar fascia in the arch of the foot may be inflamed. The skin often has extensive scaly dryness: psoriasis. Mucus membrane irritation, specifically urethritis, can occur. A nonsteroidal drug called indomethacin works well here. Also, rheumatoid arthritis medications called tumor necrosis factor blockers may help in difficult cases.

While psoriasis and the arthritis associated with it both are worse in the presence of HIV, improvement can be seen during combination therapy. There is a wide range of HIV-associated muscle diseases, starting with the marked muscle aches (myalgias) often seen at the time of seroconversion. About a third of HIV patients have some myalgia or fibromyalgia, which also includes joint pain. As in HIV-negative patients, nonsteroidal drugs and antidepressants can help.

Polymyositis is muscle inflammation characterized by mild weakness in the large muscles and an elevated enzyme called creatine phosphokinase. The cause is unclear, but biopsies usually show infiltration of CD8 cells. Steroids usually help, but immunosuppressants may be needed.

Unique to HIV is diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome, indicated by enlarged parotid salivary glands at the angle of the jaw in front of the ear. DILS also includes dry mouth and higher levels of CD8 cells, which are the prominent infiltrates in the parotid glands. Prednisone or local radiation may be used to shrink the parotid glands.

Interestingly, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus may go into remission during HIV infection. When HIV is controlled, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus may return or sometimes even appear for the first time. This would correlate with the observation that T cells are part of this inflammatory process.

If this brief overview of rheumatology is hard to follow, know that most of us primary HIV treaters often rely on rheumatologists to treat such conditions. All you must remember as a patient is that your aches and pains are real and should be addressed.

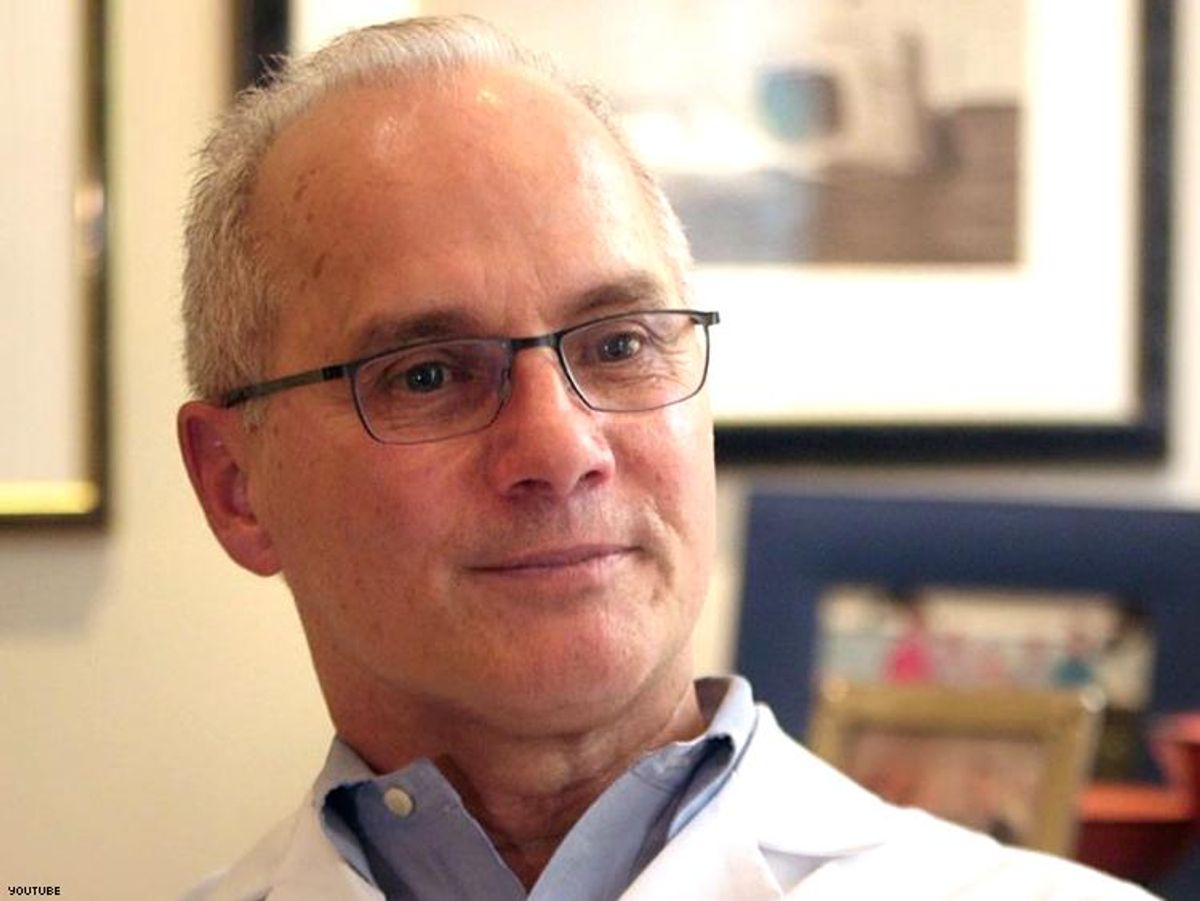

Dr. Bowers is board-certified in family practice and is a senior partner with Pacific Oaks Medical Group, one of the nation's largest practices devoted to HIV care.