Peter Staley was working on Wall Street when he was handed a flyer for a "Massive AIDS Demonstration" taking place in front of The Trinity Church, just a block away from the trading floor. "AIDS is the biggest killer in New York City of young men and women," it read, listing demands that included the Food & Drug Administration expanding access to potentially life-saving drugs and for the U.S. government to establish a "coordinated, comprehensive, and compassionate national policy on AIDS."

Two hundred and fifty people showed up. This was March 24, 1987 — the first demonstration carried out by ACT UP. Staley had received his own diagnosis two years prior and was desperate to learn anything he could, anything that might buy him more time. He joined ACT UP at their next meeting and within a year had left his job to devote every hour that he had to the group.

"And you knew that we were going to change the world," he says on this week's LGBTQ&A podcast. "We didn't know in what way. We didn't know if we'd succeed. But we knew we were going to be out there making a difference for the next few years. It felt like history."

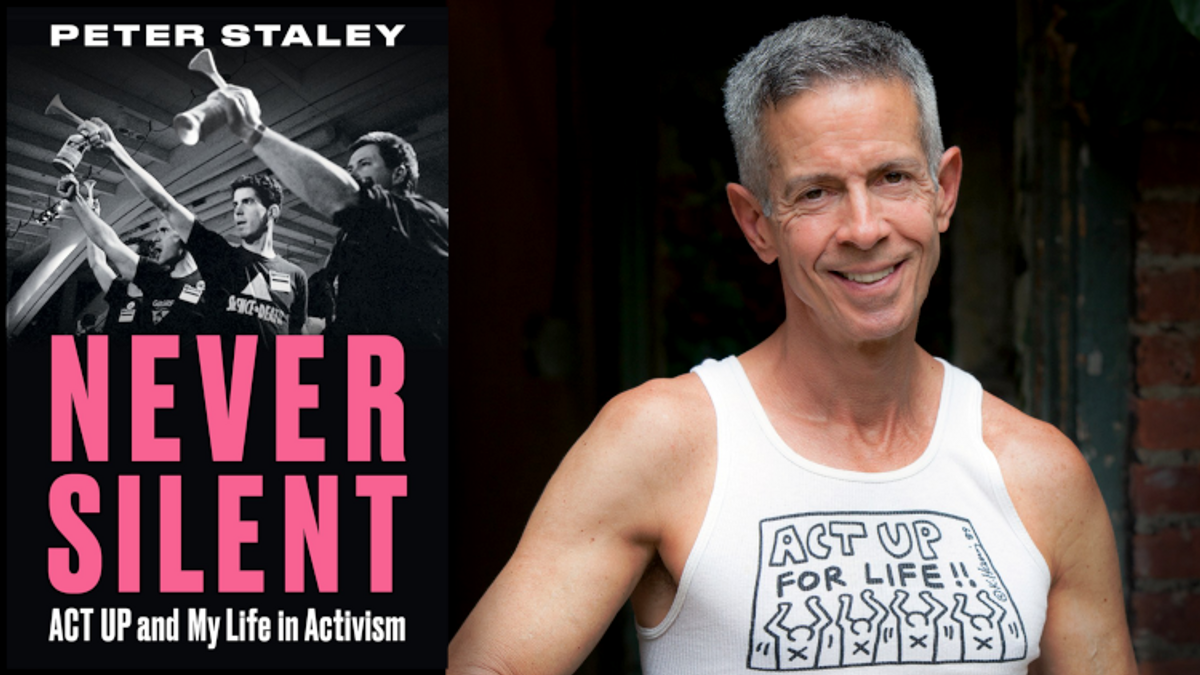

Staley, a now-legendary member of ACT UP, shares stories from his lifetime in activism, in ACT UP and after, in his new memoir, Never Silent (out now). It's a crucial behind-the-scenes look at some of the most significant moments in modern queer history.

Staley joins theLGBTQ&A podcast to talk about his time in ACT UP, how much has changed for people living with HIV with recent medical advances, and why he's optimistic that he'll see an HIV vaccine in his lifetime.

You can read an excerpt below and listen to the full interview on Apple Podcasts.

JM: You joined Act Up in '87 just as the group was getting started. Do you think you would've joined so early had you not known your own status?

PS: Probably not. I've always been very upfront that I came to the movement for very selfish reasons. I was desperate. I was afraid I only had a few years to live. I was trying to learn everything I could as quickly as possible to see if I could buy myself some time.

And that included learning about the gay community in New York, which, as a closet case, I only knew the bars. I didn't know who Larry Kramer was. So I was on a steep learning curve and within months of attending those meetings, I was shedding that selfishness and getting caught up in this community response. We were doing something that would impact far more people than those in the room. We were going to change the world. It was very obvious from the get go.

JM: It surprises me that it was obvious to you from Day 1 how effective ACT UP would be.

PS: I mean the first action...I hadn't even joined the group. I got handed a flyer on my way to work on Wall Street. Their first action was on Wall Street and it was on the nightly news. We live in a very gay world now that's integrated with the world, but back then gays were hidden and not talked about. And we weren't on the news. So the very fact that we took to the streets on mass and laid down our bodies and said, Take us away. Arrest us. That was a major news story. America had never seen us do that consistently week after week, month after month.

I got there right after that first demo. There were already over a hundred people in the room and the energy was just palpable. There were some veterans of Stonewall there. There was a hardcore group of lesbians who had lots of movement experience with reproductive rights and anti-war and the post-Stonewall radical activism that had died out in the early '70s. And you could see in their eyes that they hadn't seen anything like this since Stonewall and that they knew it wasn't a popped balloon that everybody was worried might fizzle out in a week. It was a broken dam and the water was gushing.

And you knew that we were going to change the world. We didn't know in what way. We didn't know if we'd succeed. But we knew we were going to be out there making a difference for the next few years. It felt like history.

JM: ACT UP stands out, to me, for their sense of humor. A lot of their actions had a levity, a queer sensibility to them. What was the purpose of humor?

PS: Well, first off it was a kind of humor. It was very dark. I think it's part of the queer experience, right? We are the Michelangelos of dark humor and we would not have gotten through those years if it weren't for that. If we didn't decide from the get-go that we were going to burn the candle at both ends: do our activism full-on, but at the same time, passionately live like we've never lived before.

There is no way we could have gotten through the tragedy that was those years, the constant memorials and the loss of friends and lovers and the hospital visits that were unrelenting. The emotional damage that we were accruing. The PTSD that we eventually all suffered. There's no way we would've gotten through that without a heavy dose of sex, love, humor, community. It was a surreal existence.

JM: Because things were so dire, you also had to find ways to have fun.

PS: And the clubs were at their best in New York, every weekend we would, ACT UP would dominate the best gay dance floors in New York. And ecstasy was a new drug, so we were popping ecstasy right and left. It was pure. It was the best ecstasy. Oh my God, I have great memories of those times.

And people don't realize we were the most sex-positive movement in American history, which is very strange given that people consider that Larry Kramer kind of founded the group by giving this speech that sparked our existence. He's not known for his sex-positivity.

There was certainly a national feeling that gay men should stop having sex altogether and our in-your-face counter was, No, safe sex works. We know it works and we're going to have lots of it to show you it works. So we became a very, very sex positive.

I think it was the most beautiful moment in queer history, in many respects, and something we can feel very proud of. I think it relaunched the modern gay rights movement, everything that came after: gays in the military, gay marriage, fully embracing the T in LGBT in recent years, is all because of the proud, out, indignant form of activism that ACT UP created.

JM: In 1985, you were told that you’re living with HIV. Did you assume that you'd never have sex again?

PS: I mean, that's one of your first thoughts. But you begin worrying about that a few months later. The first thing you're thinking about is, I'm not going to be on this earth for much longer. It really was a death sentence back then. There were no treatments in '85 and it was considered 100 percent fatal. So it was a scary time.

And then I went to a support group the following year that GMHC was running. And I was hearing from most of the guys in the room that they had stopped having sex altogether. They thought that they were tainted meat. And I was already boning up on the science and knew that the CDC had come out and said that condoms work. So, I was ready to get back into the game. There was one guy across the room from me who started, started saying, "Well, I'm not going to stop having sex. Safe sex works and I'm going to have plenty of it." And I was like, "That's the guy I want to talk to." It turned out to be Griffin Gold, who is one of the founders of the People With AIDS Coalition.

JM: I was surprised to read in your book that you've been undetectable since 1996. You haven't been able to transmit the virus in over 20 years, and yet I feel like the community has only learned what undetectable means relatively recently.

PS: And we have a gay-run public health messaging campaign to thank for that called U=U, undetectable equals untransmittable.

The science that clearly definitively spelled out that a person with HIV who has an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus...that science did not come until recently. Around 2008, 2009, 2010, we had early data from the get-go that it most likely blocked transmission, but the huge confirmation trials that would convince the rest of the world and convince HIV negative guys, that it's safe to sleep with a positive guy that didn't come until 10 to 15 years ago. The U=U campaign had to get launched in order to spread that message. And that's why most people haven't heard about it until the last decade.

JM: What was it like to learn that you cannot transmit this virus?

PS: You know, I've felt liberated ever since the condom, frankly. But yeah, this is even more so. And the more so for me is not so much my own...you know, I didn't suffer from self-stigma in that regard.

From '96 on, I have not worried about infecting another person. But I have always worried about the backlash of somebody freaking out after I've had sex with them. And now that is going away and it's in a whole new world and it's so liberating. I mean, I don't want to have to keep comforting unwarranted fears in other men. And we're all finally learning. HIV stigma has plagued us as long as HIV has. And we're finally making a dent in it and the world is better for it.

JM: You left ACT UP in the early 90s. Your story today is intimately tied to ACT UP, but it wasn't a happy split. Have you always been able to look back on your time in ACT UP fondly?

PS: Oh God, yes. It was, by any measure, the greatest years of my life and certainly the last year and a half were very, very painful with the infighting that started. But the three and a half years before that were lightning in a bottle and it was glorious.

JM: When did you start to feel the LGBTQ+ rights movement moving on from HIV/AIDS?

PS: It was shocking how quickly that happened after the breakthrough in '96. When the treatments started saving lives on mass, the community pivoted. Like 90% of HRC and NGLTFs agenda all through the eighties, up until '99, AIDS was 90% of their agenda. They were doing very little gay rights. Two years later, it was less than 10%.

They pivoted is so fast to gays in the military and then gay marriage. It was like a slap against the face of everybody who had been in ACT UP and who was living with HIV. We felt abandoned in a sense and we felt the history was being abandoned.

JM: Are the medical advances with COVID-19 going to help us find a cure faster?

PS: I think it's going to help COVID is definitely teaching both parties how necessary it is to invest in public health and AIDS will get a share of those increases. I think we will easily get very large increases in the NIH budget for many years to come. We will certainly get a strengthening of the CDC, which never got much increase even during the AIDS years. So there'll be big investments in public health.

The medical challenges of HIV cure research and HIV vaccine remain enormous. These are still extraordinarily hard challenges, but the money invested towards them will increase. And I am convinced I will see both of those in my lifetime.

JM: You're 60. You're 100 percent sure it'll happen in your lifetime.

PS: Yeah, I think within 10 years. I have had 2030 as a mark in my head for the last decade or more, as far as what we call a functional cure, which might not necessarily be a sterilizing cure in the sense that a person with HIV can take something that primes our immune system, so that our immune system can control the HIV on its own without the need for daily drugs. That's called a functional cure. A sterilizing cure is getting HIV completely out of the body. We might not get there by 2030, but you know, a functional cure where you take an HIV vaccine and then I don't have to take anything ever again...I'd take that. That sounds pretty good.

Listen to the full podcast interview on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Never Silent by Peter Staley is out now.

You can also listen to LGBTQ&A's interview with ACT UP historian, Sarah Schulman here.

Or listen to Ann Northrop recount the story of ACT UP's infamous Stop The Church protest that she attended with Peter Staley here.

LGBTQ&A is The Advocate's weekly interview podcast hosted by Jeffrey Masters. Past guests include Pete Buttigieg, Laverne Cox, Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, Billie Jean King, and Roxane Gay. New episodes come out every Tuesday.