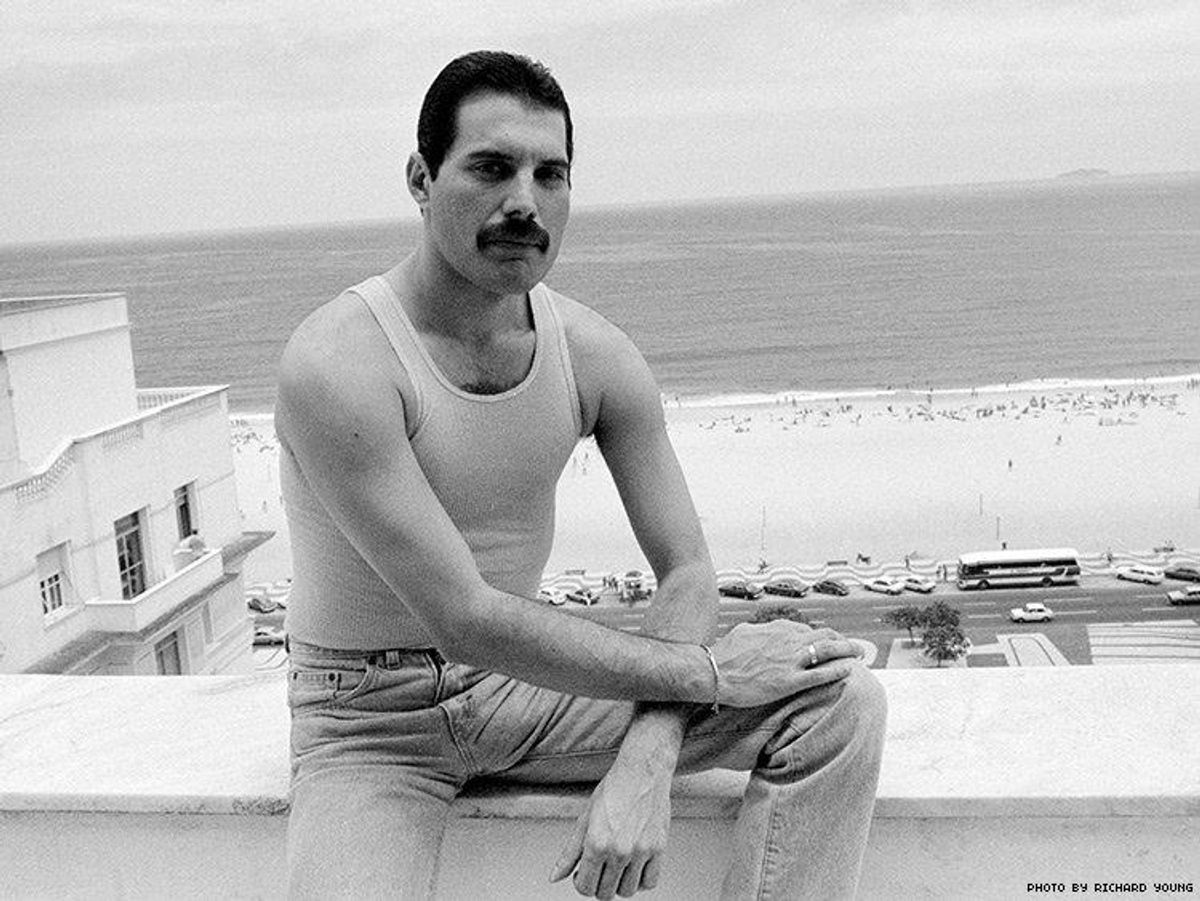

As the singer lay in what would become his deathbed, medication coursed through his veins, introduced into his bloodstream via an expensive Hickman catheter implanted in his neck. The drugs and a faithful servant would stave off pain and nausea so he could enjoy his elaborate Japanese gardens and lovingly curated London home a bit longer. By the time he decided to go off of AZT, a gaggle of paparazzi and celebrity watchers were stationed outside his home, each trying to get a glimpse of the much-loved man as he withered away. It seemed that even at the hour of his death, everyone wanted a piece of Freddie Mercury.

In Somebody to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury, authors Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne offer the first bio of the famous musician and lead singer of Queen juxtaposed with the anthropological history of HIV. It is not the history most know, the one that cites the so-called Patient Zero theory in which a sexually voracious flight attendant introduced the disease to male lovers across the globe. Indeed, that theory has been proven wrong in recent years. Instead, the authors of Somebody to Love go back to 1908, the year that the virus that became HIV would cross from chimps to hunters. Just coincidentally, that’s the year Freddie Mercury’s father was born, a Persian who immigrated from Iran to India in order to escape persecution by Muslims.

Freddie & Roy Thomas-Baker at Sarm East Studio

“Freddie Mercury was one of the first high-profile stars to die from the disease, and his story and the story of AIDS are, to some extent, inextricably linked,” Langhorne says. “It was important to us to use the format of a biography to tell the story of the disease, and who better than Freddie Mercury?” This is biography unlike others, with Mercury’s story of growing up in an Indian boarding school, a Parsi kid insecure about his overbite and in love with music, alongside contemporaneous scientific information about HIV.

The volume will surprise readers expecting a simple fan-focused, photo-filled celebrity biography. Langthorne says that was the point: “A fan of his would never pick up a book about HIV and AIDS, so we wanted to weave the two together, and so it became in itself an opportunity to inform people who wouldn’t necessarily know about this terrible disease and the struggle people lived through.”

Had he not died in 1991 of AIDS-related pneumonia, Mercury would now be 70 years old. But 25 years after his death, the Mercury bio seems as relevant as ever, obsessed as we are with sexual orientation and public identity, health care and resilience, stigma and strength.

Mercury was a curious man, a flamboyant personality long before he was aware of his own same-sex attractions. He developed a relationship with a woman in his youth, Mary Austin, who he would call the love of his life (even while in a long=term relationship with another man) and to whom he left nearly his entire estate and his ashes to secretly distribute. While he was with Austin, Mercury began having sex with other men. When Mercury reportedly told Austin he was bisexual, she said, “No Freddie, you’re gay.”

The authors of Somebody to Love do their best to dissect why Mercury loved other men but put Austin above all others. Perhaps it was gay shame, Mercury’s internalized homophobia echoing society’s belief that gay relationships weren’t “real” relationships. But I kept wondering upon reading, could he really have just been bisexual, in a world that flirted with the notion but didn’t — and still doesn’t — understand bisexual identity, especially in men? In a world where any man who has sex with men is automatically considered gay no matter how much he professes a love of women, could Mercury truly have felt torn between these two sides of himself?

It’s an open question, even for the authors, how Mercury would have identified were he alive today.

“I would like to think that by now Freddie would have come out of the closet,” Langthorne says. “The world has changed so much. He was recording artist in the ’70s and ’80s, two decades when the level of homophobia is difficult for anyone born after 1980 to fully comprehend. In particular, Britain and the USA were scary places for gay people, and the onset of AIDS gave license to the religious fulminators and right-wing zealots.”

In fact, Langthorne says he hopes the book “sheds light on the darkest times that so many lived and died through.”

Langthorne himself is a lifelong fan of Queen, in part because the earliest iteration of the band (as Smile) recorded one of its first demos in the bathroom of his stepfather’s cinema, the Regal, in Wadebridge, England. There was also a story that the band played a concert at the village hall in the small town where Langthorne grew up in, something that was finally confirmed in research for this book. The author says he saw Queen live at Wembley Stadium in 1986 on the Magic tour, its final tour with the original lineup, a concert that will stay with him forever.

Backstage, Queen 'Breakthru' Video Shoot, Nene Valley, 1989

Richards says he and Langthorne felt the 25th anniversary of Mercury’s death was the right time to reevaluate the musician’s life. And Somebody to Love is a worthy and moving read with new information unknown to even ardent fans. It’s the first book to look in detail at Mercury’s battle with HIV, not just his struggle to keep his illness a secret (he announced he had AIDS only the day before he died), but also his sexual awakening, his relationships, and the aftermath of his death, which was rife with homophobia. The book details that cultural homophobia and the way in which it affected Mercury’s decisions around treatment and his public persona, even influencing his decision to stop appearing in public. At his last public engagement, he was gaunt, with no mustache, and sporting an oversize suit; his only words were “thank you.” The book even narrows down the window of time in which Mercury may have been infected with HIV:

“It was during the U.S. leg of the tour that Freddie pursued his desire for gay sex in New York and on September 25th, while appearing on Saturday Night Live, he began exhibiting some symptoms associated with someone recently infected with HIV. In fact, he had secretly seen a doctor in the city some weeks earlier suffering from a white lesion on his tongue (likely to be hairy leukoplakia, one of the first signs of HIV infection) and this points to the period between 26th July and 13th August 1982 when Freddie contracted HIV during a break in the tour in New York.”

While the language is occasionally clunky and at times outdated (some readers will cringe reading “homosexual” used in nonscientific literature), there is also some interesting analysis that queer studies students could debate for days. One of them is over the song “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which some have suggested is Mercury’s coming-out opus.

Langthorne and Richards still couldn’t get the members of Queen to comment anew upon it. “Freddie never confirmed that ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ was his coming-out song,” Langthorne admits. “And the other members of Queen who have spoken on the subject have refused to be drawn on the matter.”

But, he says, many analyses of the song “point to it being a confessional and an illustration of his emotional setting during that period. At the time of writing he was already embroiled in an affair with David Minns despite living with Mary Austin.” It was Mercury’s first affair with a man; he had been living with Austin for seven years at the time. Music scholars Sheila Whiteley (author of Queering the Popular Pitch) suggest the lyric “Mama I killed a man” could be his confession that the straight Mercury is gone; and “Mamma Mia let me go” may be a literal plea to Mary Austin to understand he has to leave.

A six-minute operatic rock bonanza, “Bohemian Rhapsody” has been covered by artists as diverses as Elton John, Axl Rose, and Panic! at the Disco, and among its many awards and placement on the “greatest songs of all time” lists, it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2004.

Queen’s manager at the time, John Reid, spoke to Richards and Langthorne for the first time about the subtext of “Bohemian Rhapsody.” “There’s been so much analysis of the song, but I subscribe to the theory, and I never discussed it with [Freddie], that it was his coming out song,” says Reid.

Langthorne says that Mercury considered “Bohemian Rhapsody” to be his greatest accomplishment. Whether or not is was an autobiographical testimony to his homosexuality, the tragic narrative of the song’s text would take on an even greater meaning after his death.”

Pairing the musician’s personal history to the medical and cultural environment in which he lived and died, the book is a reminder of how far we’ve come, what we have to lose, and — especially in terms of HIV, our understanding of bisexuality, and sex with men — exactly how far we have yet to go.