Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

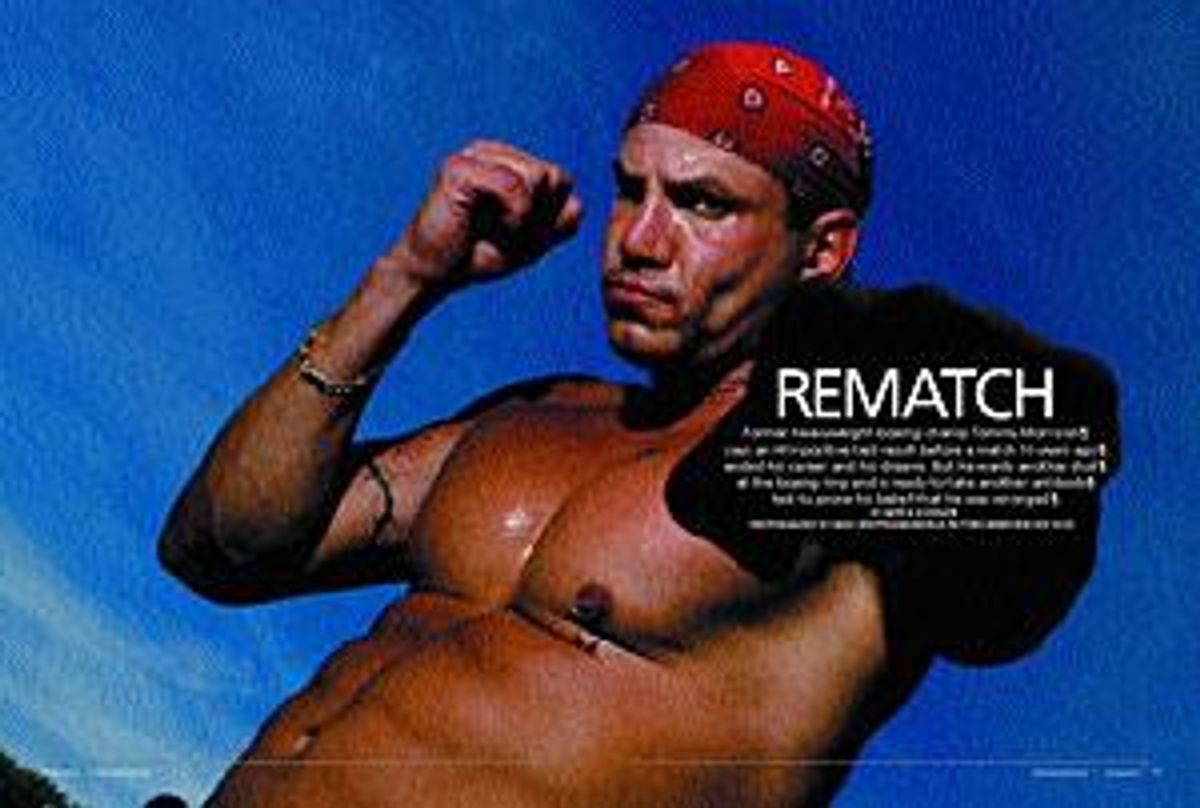

If you look under frustration in the dictionary'and if Webster's even had the necessary space'one could conceivably find the decade-long saga of Tommy Morrison. Yes, that Tommy Morrison, the one who defeated George Foreman in 1993 to become the World Boxing Organization's heavyweight champion, starred with Sylvester Stallone in Rocky V in 1990, and seemed to have the world at his feet'until 1996. That year in one controversial instant his whole world came crashing down.' While in Las Vegas for a fight to be televised on Showtime, Morrison had a prefight HIV antibody test performed by the Nevada State Athletic Commission. During the telecast it was revealed that Morrison was suddenly on a flight home to Oklahoma because, according to the commission, he had tested positive for HIV and the promoters'though not obligated to do so'had immediately scrapped the fight. Although at the time there were no laws or regulations preventing HIV-infected boxers from fighting, Morrison knew it would be nearly impossible to persuade HIV-negative boxers to fight him and that no promoter would handle an HIV-positive fighter. Although Morrison was only 27, his promising career was effectively over. What followed'depression, despair, 14 months in prison on drugs and weapons charges, and financial and personal loss'pales in comparison to what Morrison says hurt him even worse: In the minds of many he ceased to even exist. 'Nobody wanted to talk to me, return my phone calls, or even wave to me on the street,' he recalls angrily. 'That messed with me emotionally. I never thought in a million years that that would happen to me. For six or eight months I blocked it out and tried to go about my business, but people just would not accept me living my life and acting like nothing happened. I was the talk of the town.' The town in question is Jay, Okla. Population: 2,482. Morrison had grown up there, and it's where he immediately sought shelter from the prying eyes of the ravenous press. 'But there's no way to reason with these people,' he says. 'It's a small-town mentality, you know?' 'Everybody who was a friend just left me,' Morrison continues. 'It was a conspiracy of some sort. Right when I really started to get it all together, that's when I couldn't box anymore.' Can't Fight or Make Flight In the days that followed the HIV revelation a tidal wave of hysteria consumed Morrison's every move. Reporters camped out at his house, and helicopters flew over his roof. Morrison says he shut down. 'As soon as you're [diagnosed with HIV] you're immediately discriminated against,' says Glendale, Ariz., attorney Randy Lang, who has taken on Morrison's case. 'You get depressed; you get confused instantaneously.' With Morrison's contract with his promoters ended after the testing announcement, he had no avenue to challenge the test result obtained by the athletic commission'or even to validate the test's accuracy. Feeling like he had run into a brick wall, Morrison began spiraling downward emotionally and fell out of the spotlight. 'For 10 years people have told me to sue [the Nevada State Athletic Commission over the testing result], but I just wanted to get the fuck away from it,' Morrison says. 'I didn't used to have any goals. I was paid to fight, and I lost my passion for the sport. And the way I had to exit the sport wasn't exactly the most glamorous way either. But all the problems I had are because of being kicked out and discriminated against in the sport of boxing.' The confusion and mixed emotions Morrison struggled with even led to poor choices regarding his personal behavior and the people he associated with. They also contributed to one of the lowest points of his exile, when he was jailed in 2000 after police found prescription drugs and a gun in his car. 'I was locked up for 14 months, eight days, six hours, 46 minutes,' he vividly recalls. Other prisoners, he says, 'even tried to kill me once.' Shortly after his retirement, Morrison's ranch home outside of Tulsa, Okla., mysteriously burned to the ground along with most of his possessions. Although he has no proof and an official investigation didn't support it, Morrison has long suspected arson. An Upbeat Outlook Today, as Morrison recounts his past, he has very clearly had a change of heart about his sport, thanks in part to his spirituality and new legal options he has been exploring to get back in the ring. He's still fit, trim, and healthy'he says he's never had any HIV-related symptoms'and his firmly rooted goal is to make a comeback and regain his title and professional reputation. More important, however, he's intent on regaining his life. 'I could have gotten so pissed off and bitter and blamed God for everything,' he says, 'but I know one thing for certain'all things happen for a reason. You just may not understand where God is leading you.' Unlike other prime-time athletes who have tested positive for HIV'Magic Johnson and Greg Louganis come quickly to mind'Morrison is intent on competing regardless of his serostatus, which both Morrison and Lang have long disputed as having been determined inaccurately. 'I think it was a false test,' Morrison says of the results of the HIV antibody analysis that were announced in place of the 1996 scheduled fight. 'I think there are millions of people walking around that are false positives.' 'This whole thing is based on what we believe was a faulty or unscrupulous test,' echoes Lang, who feels that Morrison's well-documented steroid use might have contributed to a tainted result. Morrison contends that at the time he was told he was HIV-positive he never saw a doctor or any medical report to confirm his positive serostatus; he was swept up in the hysteria of a positive test result, according to Lang. 'He never got a chance to dispute any of it. They just rushed him onto a plane and shipped him back to Oklahoma,' says Lang, who believes Morrison should have been given the benefit of the doubt at the time of the fight. He says there should have been a demand for a second medical opinion and a postponement of the fight until an independent test could be administered to ensure it was a valid test and not a laboratory mix-up. Although Lang is vague when discussing whether Morrison's doctors believe he is indeed HIV-positive'saying only that they report no 'degeneration or acceleration' of an infection'he does add that at the urging of caregivers Morrison briefly tried some of the newest anti-HIV medications that started becoming available in 1996, which was the beginning of the combination therapy era. Morrison quickly stopped taking the meds, though, because he says he is wary of antiretroviral medications in general. 'There was no way I was going to take that medicine,' the former champion says. 'One thing I know for sure is that doctors will kill you if you let them.' The Challenge Ahead Because Morrison has been asymptomatic all these years and lab tests show no detectable levels of virus in his bloodstream, he firmly believes his original HIV antibody test was a mistake. 'I don't think I ever had it,' he says. 'For years it's been completely undetectable in my body. To me that means it's not there.' But Daniel Bowers, MD, an HIV specialist and partner at Pacific Oaks Medical Group in Beverly Hills, who is also a columnist for HIV Plus, says having an undetectable viral load doesn't 'rule out or rule in' HIV infection, particularly given Morrison's claims that he never saw proof of his initial positive HIV antibody test. 'It is truly possible that he may be a long-term nonprogressor,' someone who is infected with HIV but whose immune system keeps the virus in check, Bowers continues. 'But it also could be that he's HIV-negative.' Without a full HIV workup by an HIV specialist, Bowers says, it's impossible to know which of the two Morrison may be. It's also a possibility'though a remote one'that Morrison may have received a false-positive test result, Bowers adds. 'The testing technology has not changed since 1996,' he says, 'and the interpretation has not changed. You could have a doctor or official look at the test and misinterpret the results.' A lab error'like a mislabeled vial or an accidentally switched blood sample'also could have produced an inaccurate result, say Morrison and his attorney. But could all this simply be wishful thinking on Morrison's part? 'If I had a penny for every time someone told me I was in denial,' Morrison says flatly. 'But that's when you refuse to believe the situation is for real. I knew it was real. I knew that it cost me $40 million, that I'd worked over eight years of my life'blood, sweat, and tears, hard work'just to get to that one pinnacle fight, and I wanted to be able to leave boxing as a good example to follow.' Morrison is determined to get that one more chance, though. He's training in Phoenix with a clear focus on a triumphant comeback. But his first'and no doubt toughest'hurdle won't be in the ring. Morrison knows he'll have to face another high-profile medical exam before he can fight again. For now, his exact timetable remains under wraps. 'At the right time I'm going to go to Vegas with my team,' he says. 'I'm going to take the same HIV test, and they have to show me that I don't have it.' Facing His Demons But even the worst-case scenario'another positive test result'isn't going to take away his dreams'not this time. 'Irrespective of this, Tommy can fight internationally'in Japan, Canada, or other countries,' Lang says. 'People who don't want to fight him'if they don't have the guts'so be it.' 'You're dealing with professional men who put their lives on the line every time that they go into the ring,' continues Lang, who says he doesn't expect most boxers would have a problem stepping into the ring with Morrison. 'Only if they're unintelligent or uninformed [will they have an objection], but most heavyweight boxers I've talked to say they'd be glad to fight Tommy. They said they'd love to see him come back, and they think he was wronged. They're not concerned about HIV.' One fighter, however, has gone on the record stating that he would not fight Morrison. B.J. Flores, a young fighter from Phoenix, told USA Today, 'I just don't see anybody without HIV fighting somebody who has HIV. No way.' Obviously much is riding on the results of his next antibody test. But for Morrison, the chance to be an inspiration to others is, in truth, inspiring him just as much. 'This is going to be the comeback of the century,' he says. 'Ten years ago in the eyes of society I was given a death sentence. I saw the people stop in their tracks when they would spot me. They thought I was dead. It was even printed in some magazines. This is going to be one of the most amazing stories. I think a lot of people are going to be truly inspired.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Why activist Raif Derrazi thinks his HIV diagnosis is a gift

September 17 2024 12:00 PM

How fitness coach Tyriek Taylor reclaims his power from HIV with self-commitment

September 19 2024 12:00 PM

Out100 Honoree Tony Valenzuela thanks queer and trans communities for support in his HIV journey

September 18 2024 12:00 PM

The freedom of disclosure: David Anzuelo's journey through HIV, art, and advocacy

August 02 2024 12:21 PM

Creator and host Karl Schmid fights HIV stigma with knowledge

September 12 2024 12:03 PM

From ‘The Real World’ to real life: How Danny Roberts thrives with HIV

July 31 2024 5:23 PM

Eureka is taking a break from competing on 'Drag Race' following 'CVTW' elimination

August 20 2024 12:21 PM

California confirms first case of even more deadly mpox strain

November 18 2024 3:02 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

A camp for HIV-positive kids is for sale. Here's why its founder is celebrating

January 02 2025 12:21 PM

This long-term HIV survivor says testosterone therapy helped save his life.

December 16 2024 8:00 PM

'RuPaul's Drag Race' star Trinity K Bonet quietly comes out trans

December 15 2024 6:27 PM

Ricky Martin delivers showstopping performance for 2024 World AIDS Day

December 05 2024 12:08 PM

AIDS Memorial Quilt displayed at White House for the first time

December 02 2024 1:21 PM

Decades of progress, uniting to fight HIV/AIDS

December 01 2024 12:30 PM

Hollywood must do better on HIV representation

December 01 2024 9:00 AM

Climate change is disrupting access to HIV treatment

November 25 2024 11:05 AM

Post-election blues? Some advice from mental health experts

November 08 2024 12:36 PM

Check out our 2024 year-end issue!

October 28 2024 2:08 PM

Meet our Health Hero of the Year, Armonté Butler

October 21 2024 12:53 PM

AIDS/LifeCycle is ending after more than 30 years

October 17 2024 12:40 PM

Twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir, an HIV-prevention drug, reduces risk by 96%

October 15 2024 5:03 PM

Kentucky bans conversion therapy for youth as Gov. Andy Beshear signs 'monumental' order

September 18 2024 11:13 AM

Study finds use of puberty blockers safe and reversible, countering anti-trans accusations

September 11 2024 1:11 PM

Latinx health tips / Consejos de salud para latinos (in English & en espanol)

September 10 2024 4:29 PM

The Trevor Project receives $5M grant to support LGBTQ+ youth mental health in rural Midwest (exclusive)

September 03 2024 9:30 AM

Introducing 'Health PLUS Wellness': The Latinx Issue!

August 30 2024 3:06 PM

La ciencia detrás de U=U ha estado liberando a las personas con VIH durante años

August 23 2024 2:48 PM