Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

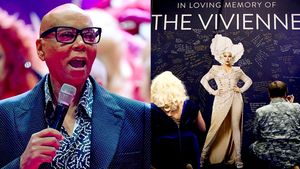

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Duane Cramer didn't choose the world of photography. He inherited it. When he was a teenager his father gave him his first 35-millimeter camera. More than just a gift, it was the passing-on of a family tradition'a responsibility, of sorts, to know not only who he was but where he was from. It was a mission he took to heart. As proof, one need look no further than the walls of his San Francisco loft, where photographs he has taken mingle with images captured by and of his relatives more than 100 years before. Cramer's body of work refracts his life as a black gay man living with HIV. Born in Indiana in 1962, Cramer and his family moved to State College, Pa., when his father was hired as a business professor at Pennsylvania State University. After high school he headed west to Los Angeles to attend the University of Southern California, where he earned a bachelor's degree in business. He graduated in 1984 and immediately went to work for Xerox, where he stayed for the next 17 years. As a sales manager for the company, Cramer moved in 1990 to San Francisco, where he quickly became involved in the city's gay- and HIV-related causes. Throughout the years his camera rarely left his side. Now 46, Cramer, a gifted, self-taught photographer, is known internationally for his work. His desire to record, preserve, and improve people's lives is evidenced both in his photography and in the work of the organizations for which he has volunteered or served as a board member: the Names Project, which manages the AIDS Memorial Quilt; San Francisco's LGBT Community Center; Frameline, which produces the San Francisco International LGBT Film Festival; the Black AIDS Institute; and the Millennium March on Washington, held in April 2000. Cramer's loft is both his home and his studio. The high-backed chair with curved arms and legs and the large, round, black-rimmed mirror seen in many of his published works are as much a part of his living space as his camera and photography equipment. Three gold-framed pictures painted by his uncle decades ago follow the stairs up to his bedroom. One captures Cramer as a boy, at about age 6, a paper airplane lying on the table before him. Folded across the top of the frame is the striped T-shirt the young Cramer wears in the painting. He found it eight years ago in a family storage unit in Texas. Above Cramer's desk, three large black-and-white photographs hang side by side in black wooden frames. The gauzy image of Italian screen star Maria Grazia Cucinotta and the photo that captures the majesty and wit of former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown are both by Cramer. The third, a stalwart image of Cramer's grandfather and a male friend, dates to the 1920s. Each can clearly stand alone. As a triptych, they embody a vision that connects art, family, and community. How did your home become a family archive? One of the things that really interests me about photography and visual art is the ability to document people's lives. It's kind of funny, since Xerox [where Cramer worked for many years] is 'the document company.' And here I am documenting. I'm really fascinated with family. Many of my subjects are friends and family, so I'm documenting their lives and my life. I have hundreds of photos of my family, some dating back to the 1800s. When my maternal grandfather passed away I inherited and took over his collection, and I have been having these images restored over time'copying negatives, filing, archiving, and understanding the history of my family, which is very multiethnic. I have African, Latin and Native American, and Irish roots. And my grandfather on my father's side was of German-Jewish descent, which is why my last name is Cramer. I will pass this on to my nieces and nephews by leaving this collection behind for them. You often speak about your father, Joe Cramer. My father died 22 years ago, in 1986. At the time he was the associate dean of the business school at Howard University in Washington, D.C. I was in my early 20s, and he was the first person I knew to die of AIDS. What's really remarkable is that to this day I know very few people who have passed away from AIDS. Was that a catalyst for your work? For many years after my dad's death there was a lot of shame and guilt. We used to tell people that he died of cancer. It took many years for my mother and my sisters to become open and public about his death from AIDS. In the mid 1990s we made a panel for the AIDS Memorial Quilt for my father. I also became a member of the Names Project board of directors, and I helped to organize the last display of the entire quilt'in Washington, D.C., in 1996. It was terrifying and freeing to come out about my father's death from AIDS; it was so much weight I'd been holding onto for so long. The quilt display was a turning point in my life in many ways. That weekend I wasn't feeling quite right. When I got back I had an HIV test and got a call from my doctor. That's when I knew I was HIV-positive. I have always been very aware of my sexual practices and what I do, but I had broken up with my partner that year and had one situation with this trick where I did not have safe sex. I have pretty much pinpointed that as the situation where I became infected, and I think the reason I wasn't feeling well that weekend in Washington is because that was when I seroconverted. So much of your work'as a photographer, as an activist'directs attention to those who all too often go unseen. One of the reasons I joined the board of the Names Project was because the quilt was not as diverse and reflective of the epidemic itself. It was reflective of the white men who had died of AIDS. One of my goals was to help people of color to figure out ways to use the quilt to grieve the loss of people in their lives and make it more reflective of the actual epidemic. In 1998 I was awarded a paid one-year social-service leave from Xerox. During that time I served as the national coordinator for a program run by the Names Project, and I took the quilt to middle and high schools around the country. I went everywhere'from Alabama to New York City to St. Louis. Our goal was to enhance school HIV education programs. I would pull out sections of the quilt that had young people of color so that kids could see images that looked like themselves and feel like, This could really happen to me. And I always carried my father's quilt panel with me'which was very emotional. When did you decide to leave Xerox to focus on your photography? I was always doing photography while I was at Xerox. But after that year traveling with the quilt, I realized I needed to figure out a transition. My work was no longer fulfilling to me, and I knew it was time to go. Also, it just felt like there were too many faces of Duane. I was in a corporate job. I was an activist. I was on boards. I was a photographer. It felt like, Who am I? My photography took off as soon as I left. That's when it became clear to me: This is what you do. This is who you are.How did your work become known? I never went into taking photographs and creating imagery for financial gain. I was making money at Xerox and taking photographs and sharing them with publications. So I think there was a purity and honesty in my work that people could see and feel. My first publication was Latin America's Harper's Bazaar en Espa'ol. I had taken photos of a friend who was a Mexican singer, and the magazine did an article on her. What brought me international recognition was my work being published in the Australian magazine Blue, which is widely known for its artistic nude and seminude photos of men. I submitted some photos to them, thinking maybe they'd print one. But they did a whole spread of my work and decided to put one of my photos on the cover. Blue is the type of magazine that photo editors at other magazines buy. So people saw my work, and I started to get phone calls from people who wanted to work with me. What was it like to have that success? When I think about my work I think about how my actions can make the world a better place and impact people in a positive way. My work is very diverse ethnically, sexually'men, women, trans, bi, black, white, Latin, Asian. There is a power in being able to project that imagery through my eyes and my lens. That's what I like to do. You've photographed many famous people. What is that like? All the photo shoots I do are fun. It doesn't matter if it's RuPaul or Mary Wilson or a friend. People are people. I'm not starstruck at all, and I think that makes people feel more comfortable. I'm often asked to photograph different people in the community or celebrities who are doing work for the community. That's how I photographed people like Bill Clinton; congresswoman Maxine Waters; and Julian Bond, the chairman of the [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]. It's not because of who they are but because of what they are doing for the community. All people are important. To me, it doesn't matter if you're famous or not. It's more about what you do with the personal power that you have to impact the world in a positive way. If you could photograph anyone, who would it be? At this moment in time it would be Barack Obama. I'm confident that I will photograph him and his wife, Michelle, together. The other person I would like to photograph'and I know that someday I will'is Oprah. I admire how she uses her personality and charisma to create positive change. You were in Mexico City in August for the XVII Inter'national AIDS Conference. What impressions did you take away? What stood out most for me'and this isn't news'is the extent to which the African-Americans have really been left behind. I was part of a delegation that included Phill Wilson, the executive director of the Black AIDS Institute; congresswoman Barbara Lee; and Pernessa C. Seele, the founder of the Balm in Gilead, and we were talking about how we continue to talk about the same thing'how funds to fight HIV in the United States continue to get cut. It's wonderful that the Bush administration is sending funds to Africa and other countries. But if 'Black America' were a country, it would rank 16th in the world in the number of people living with HIV. In fact, more people of African descent in the United States are living with HIV than in seven of the 15 African countries that receive support from the Administration's anti-AIDS program. So what I came away with was that black people in America continue to be neglected and left behind. One of the mottos of the Black AIDS Institute is 'Our People, Our Problem, Our Solution,' and it just becomes increasingly clear that it is up to us to continue to put the focus and pressure on the government to put the funds and resources where they are most needed. How has being HIV-positive affected you as an artist? HIV is the lens through which I see everything. Becoming HIV-positive made me think about making the most of every day and of every single thing that I do. Life is really short. HIV brought that to light.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Why activist Raif Derrazi thinks his HIV diagnosis is a gift

September 17 2024 12:00 PM

How fitness coach Tyriek Taylor reclaims his power from HIV with self-commitment

September 19 2024 12:00 PM

Out100 Honoree Tony Valenzuela thanks queer and trans communities for support in his HIV journey

September 18 2024 12:00 PM

Creator and host Karl Schmid fights HIV stigma with knowledge

September 12 2024 12:03 PM

The freedom of disclosure: David Anzuelo's journey through HIV, art, and advocacy

August 02 2024 12:21 PM

From ‘The Real World’ to real life: How Danny Roberts thrives with HIV

July 31 2024 5:23 PM

Eureka is taking a break from competing on 'Drag Race' following 'CVTW' elimination

August 20 2024 12:21 PM

California confirms first case of even more deadly mpox strain

November 18 2024 3:02 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

A camp for HIV-positive kids is for sale. Here's why its founder is celebrating

January 02 2025 12:21 PM

This long-term HIV survivor says testosterone therapy helped save his life.

December 16 2024 8:00 PM

'RuPaul's Drag Race' star Trinity K Bonet quietly comes out trans

December 15 2024 6:27 PM

Ricky Martin delivers showstopping performance for 2024 World AIDS Day

December 05 2024 12:08 PM

AIDS Memorial Quilt displayed at White House for the first time

December 02 2024 1:21 PM

Decades of progress, uniting to fight HIV/AIDS

December 01 2024 12:30 PM

Hollywood must do better on HIV representation

December 01 2024 9:00 AM

Climate change is disrupting access to HIV treatment

November 25 2024 11:05 AM

Post-election blues? Some advice from mental health experts

November 08 2024 12:36 PM

Check out our 2024 year-end issue!

October 28 2024 2:08 PM

Meet our Health Hero of the Year, Armonté Butler

October 21 2024 12:53 PM

AIDS/LifeCycle is ending after more than 30 years

October 17 2024 12:40 PM

Twice-yearly injectable lenacapavir, an HIV-prevention drug, reduces risk by 96%

October 15 2024 5:03 PM

Kentucky bans conversion therapy for youth as Gov. Andy Beshear signs 'monumental' order

September 18 2024 11:13 AM

Study finds use of puberty blockers safe and reversible, countering anti-trans accusations

September 11 2024 1:11 PM

Latinx health tips / Consejos de salud para latinos (in English & en espanol)

September 10 2024 4:29 PM

The Trevor Project receives $5M grant to support LGBTQ+ youth mental health in rural Midwest (exclusive)

September 03 2024 9:30 AM

Introducing 'Health PLUS Wellness': The Latinx Issue!

August 30 2024 3:06 PM

La ciencia detrás de U=U ha estado liberando a las personas con VIH durante años

August 23 2024 2:48 PM