All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

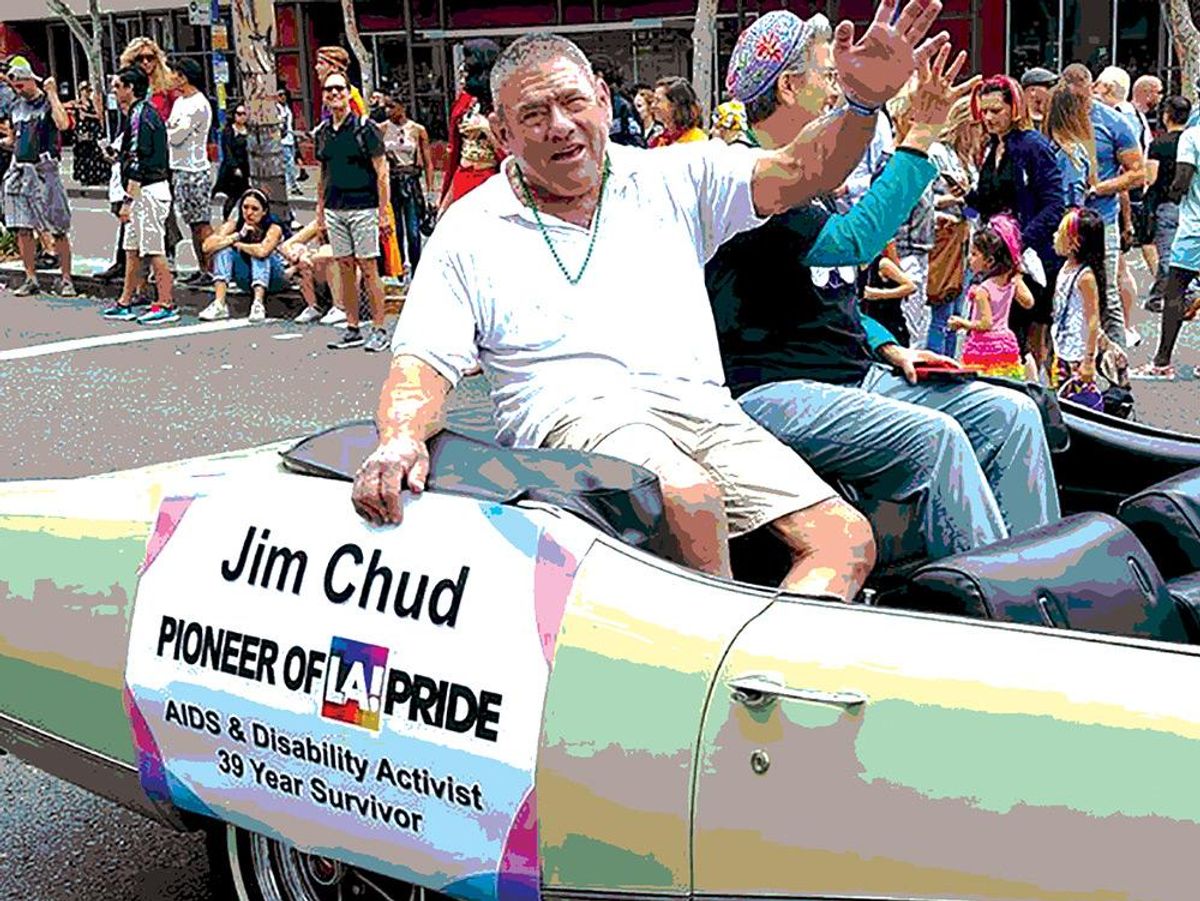

Activist Jim Chud died last week at the age of 62 from sepsis, most likely stemming from a bacterial pneumonia. According to the Los Angeles Blade, he may have been one of the first people to exhibit symptoms of HIV.

A longtime resident of West Hollywood, Calif., Chud was a member of the Disabilities Advisory Board, working as an HIV care analyst at the LA County Department of Human Services. He was also a prolific writer, having been published by publications like Huffington Post, among others.

In 2017, he lent his voice to Plus in an extremely personal op-ed about his life, work, and aftermath of being part of early AIDS clinical trials. Read his powerful piece below:

In November 1977, while a sophomore at Yale, I came down with an infection. I had night sweats, a rash, mump-like swollen lymph nodes, and thrush. My symptoms subsided in less than two weeks, and I was discharged. Walking me out, my doctor said, “You probably had some sort of virus.”

According to Science Magazine, a 2016 study indicated that in 1981, when Dr. Michael Gottlieb presented the first five cases of pneumocystis to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were already 250,000 people living with the virus. In the beginning, what was mistakenly thought to be a virulent, fast-acting virus was actually the disease proceeding along its course without intervention.

I recently entered my 40th year of living with HIV. I’ve seen a lot over those years. I still have those PTSD moments seeing my friend Jerry in a fogged-

up oxygen tent, struggling to take every breath; each inhalation made painful and difficult by pneumocystis pneumonia. His last words to me were, “Don’t let it do this to you.”

In 1987, I was living in Washington, D.C., and after two double blind studies at George Washington University, I drove to the National Institutes of Health and volunteered for whatever clinical trial would take me. I was 29, and not expecting to see 35. If I somehow hit the jackpot and the drug in my study was an answer to AIDS, then fantastic. If not, and the drug was useless — which was the more likely result — then at least I had done something concrete, even if it was just helping eliminate one of the failing therapies.

The study I was in combined high doses of AZT and DDC, a new drug by Roche Pharmaceuticals. DDC, while effective in the test-tube against HIV, was very toxic, and put all 80 of us study participants through a whole host of side effects. The mouth sores were legendary. Eating required first gargling with Lidobenelox, a thick pink emulsion of lidocaine, benadryl, and Maalox. It resembled the hand soap in public restrooms, but it provided 20 minutes of pain relief.

About five weeks into the study I experienced the side effect that would change my life forever. At a restaurant, I started dropping my utensils for no apparent reason. In a surprisingly short time I couldn’t open my mouth wide enough to put food in. Something was very wrong.

The next morning, Sam Broder, then head of AIDS research at the National Cancer Institute, came into my hospital room and said, “You, know Jim, if you can just get past this side effect, the virus just hates this drug.” Through clenched teeth I replied, “This isn’t the quality of life we discussed.”

He sighed, saying, “I guess you’re right,” and took me off the study.

My symptoms resolved in three or four days. I was told at the time that my immune system had mounted an attack on my cartilage, and that my condition was a lot like rheumatoid arthritis. What no one realized at the time was how much damage to my cartilage had occurred, or that the process would continue for years at a subclinical level.

What really surprised me at the time, was that they didn’t plan on monitoring me going forward. There was no funding for — and nothing in the protocol about — following people after the participation phase was done. It became alarmingly clear that we were considered disposable since we would probably die in a few years from AIDS. No questions would be asked about why we died. Being homosexuals made us that more disposable.

In 2003, pain in my lower back and most of my supportive joints reached a point that drove me to an orthopedic surgeon, and the first MRI in 14 years showed so much damage to my spine that at first, the radiologist didn’t believe they were my films.

In the 12 years since then, I have had over 80 operations on my spine, neck, and major joints to try to ameliorate the legacy of that clinical trial. I am now 7 inches shorter than when I entered the study, since all my disks are gone. There are more than a few people who, upon seeing me for the first time since my body building days, have no idea who I am until they hear my voice.

In 2009, I first began to depend on a four-wheeled walker to be able to walk. I had no idea what being disabled or living with a disability really meant prior to that day. My drive to do something for other disabled people shifted into hyper-drive from that moment on.

That same year, I heard that Dr. Robert Yarchoan, the head of the study in 1987, was still at the NIH, and that he had taken over as director of the Office of HIV and AIDS Malignancy at the NCI. I decided to call him and ask if NIH would see if they had any ideas for how to deal with my condition.

“Hello Dr. Yarchoan,” I said. “This is Jim Chud.”

After what seemed like a very long time Yarchoan barked, “Is this some sort of joke?”

“No,” I replied. “What do you mean? Do you remember me, Jim Chud? You know, the big guy with the joint problems?”

“No way! Really? Oh my God — it can’t be!” I could hear him yelling to someone, “Hey Kathy, you are not going to believe this, but Jim Chud is on the phone!”

I told him that my condition was what I was calling about.

He stopped me to explain his surprise at hearing my voice. “Mr. Chud, do you know how many people there are that can tell the tale of what high dose DDC can do, and did, to them?”

“No,” I replied.

“You.” He said. “Period.”

A chill ripped up my spine. I suddenly knew how loneliness really feels.

I made arrangements to go back there for a work-up, and was reminded of just how humane the researchers at the NIH really are. He was concerned, happy, and eager to see me. He offered me any resources that the NIH might have. I was quite overwhelmed by the whole occasion, especially since I knew that the funds for my visit were coming out of his administrative dollars, and would not be covered by any study or drug company.

Since that day, I have thought a lot about the other people in that study — and other studies. Those people volunteered for the task of saving lives and helping protect our nation from the ravages of the war against AIDS, much like our country’s soldiers volunteered in military conflicts across the world.

Now, when long-term survivors really need help, there aren’t any Wounded Warrior associations available to help us. I get more than a little sad when I see how the AIDS warriors — the forgotten warriors — have been treated. I have had the resources to make a life for myself, but the vast majority of people, at least in my study cohort, were already further along in their disease, and were left to fade away. That is just wrong!

The big drug companies that made and continue to make billions of dollars from the drugs that passed muster, were able to minimize their losses because of the men and women who, like myself, volunteered and received the drugs that failed. Those companies have never once reached out to any of us to offer a simple “thank you,” or to see how we were doing after our trial experiences. In my opinion, this is reprehensible.

Apparently, the doctors from NIH agree. I learned early this year that they have filed a complaint with the FDA about the clinical trial practices of Roche, using my experiences as the example. This is the first time something like this has ever been done after a drug has been removed from the market.

The work we do does matter.

Read more from our Long-Term Survivor series here.