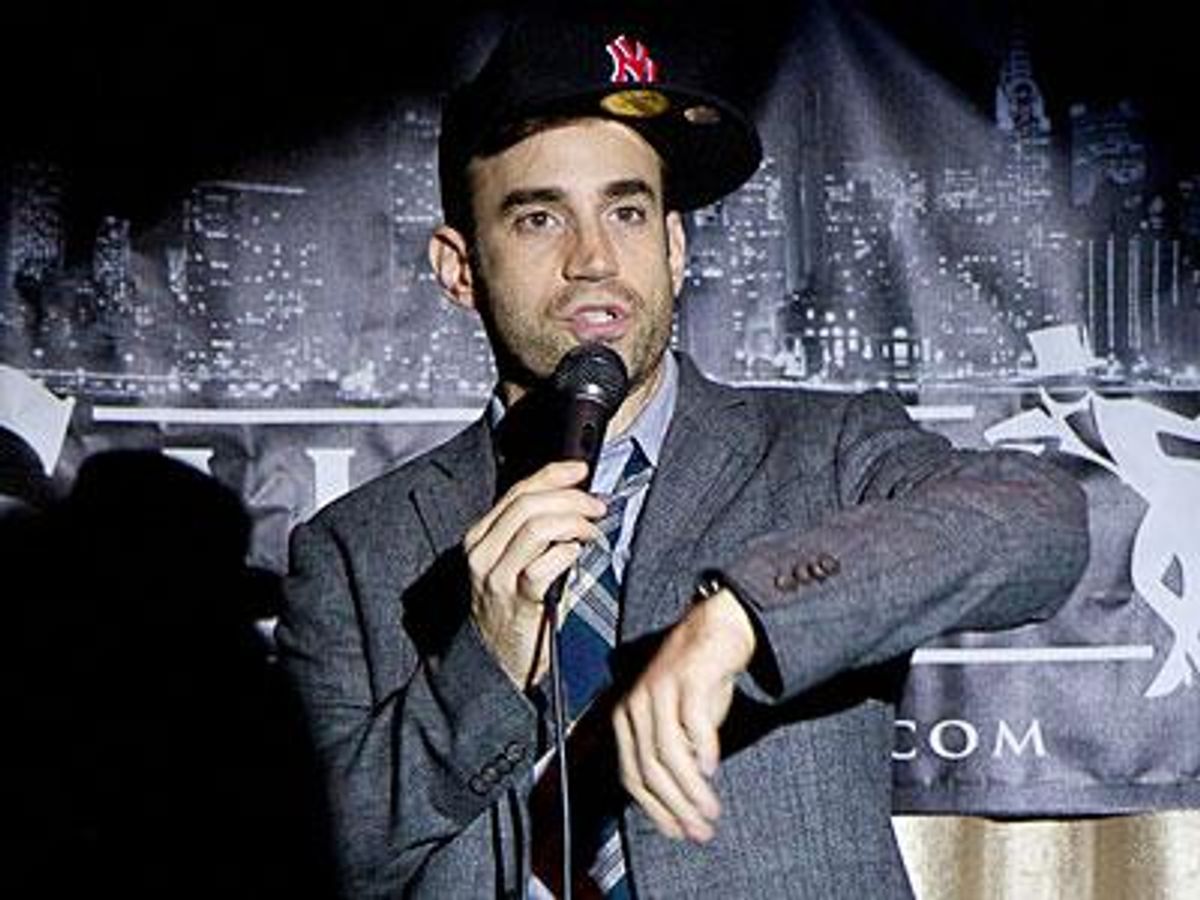

Kenny Neal Shults is the comedian we have been waiting for. Part Lenny Bruce, part Chris Rock, he is the first bona fide gay comic who's willing to really go there. Two of his funniest bits go like this: “I’m not one of these new generation gays. I don’t want to get married, serve in the military, have a buncha kids. I’m old-school gay. I wanna have sex with lots of strangers and gentrify bad neighborhoods. Maybe get a Maltese down the line…” Another favorite bit is when he says, “But then again, we used to not be represented in TV and film at all, invisible, like a tattoo on a black guy. Then we were portrayed as childless party monsters who devote all their disposable income to cocaine and strippers.” He makes a displeased face before he shouts, “What happened?”

As funny as Shults is, it's his day job where he's making the biggest difference. A few years ago he left a large public health firm to do his own form of HIV prevention by engaging directly with at-risk populations and teaching people how to make short films that act as behavior change campaigns directed at their peers. They are essentially online public service announements that aim to change behaviors and attitudes from within. The program he developed lets him engage any particular group (gay men, HIVers, teens, transgender folks, for example), and making the film alters the participants’ own perspectives and behaviors in the process. The program is called MyMediaLife and is a behavior-science fueled product that his company offers to nonprofits, service organizations, and any organization that wants to help foster social change respectfully and effectively without shaming, scaring, or lying.

Shults explains, "In public health, behavior change is everything; it's the primary tool we use to get specific groups of people to use condoms and birth control, wear a seat belt, take their meds, stop smoking, wash their hands, etc. But these same social marketing principles, that organically employ behavior science, can also be applied to any social cause that can be advanced through changes in norms, attitudes, and behaviors such as bullying, sexting, homophobia, voting, etc. It all depends on the mission of the agency and what they are funded to do."

He argues that there are many ways to motivate public behavior and attitude shifts, some effective and others less so. "In the beginning of the AIDS epidemic," he says, "telling gay men to use something that was only for straight people [a condom] was a groundbreaking strategy for preventing the spread of HIV. At that time condoms were a foreign concept to gay men. But prevention efforts never evolved, and by the mid '90s they actually caused more harm, in my opinion."

break Shults feels that the slogan "Use a condom every time" is catchy but also vague and unrealistic. "People falter, and what's more, people place value in barrier-free sex," the comic turned activist says. "No one loves condoms; they love what condoms can do for them. But eventually gay men, just like straight people, look for ways to have more fulfilling sexual experiences, such as sex with a long-term partner who is also HIV-negative. But instead of addressing gay men's ambivalence about using condoms, prevention efforts shamed them for having such thoughts. When I was in my 20s, I thought having unprotected oral sex posed the same threat as unprotected anal sex. Rather than giving gay men the facts and explaining risk as a hierarchy and letting men come up with a risk portfolio that worked for them — having more oral sex over anal intercourse — prevention efforts suggested all sexual activities were equally risky. This type of black-and-white, all-or-nothing prevention strategy gives people two options: adhere or abandon hope for surviving."

Shults feels that the slogan "Use a condom every time" is catchy but also vague and unrealistic. "People falter, and what's more, people place value in barrier-free sex," the comic turned activist says. "No one loves condoms; they love what condoms can do for them. But eventually gay men, just like straight people, look for ways to have more fulfilling sexual experiences, such as sex with a long-term partner who is also HIV-negative. But instead of addressing gay men's ambivalence about using condoms, prevention efforts shamed them for having such thoughts. When I was in my 20s, I thought having unprotected oral sex posed the same threat as unprotected anal sex. Rather than giving gay men the facts and explaining risk as a hierarchy and letting men come up with a risk portfolio that worked for them — having more oral sex over anal intercourse — prevention efforts suggested all sexual activities were equally risky. This type of black-and-white, all-or-nothing prevention strategy gives people two options: adhere or abandon hope for surviving."

These kinds of judgmental, shaming scare tactics almost always backfire, he says. In this case, they led to even more substance abuse in the gay community as cocaine and other stimulants, like crystal meth (an epidemic in its own right), dramatically reduced inhibitions and allowed gay men a temporary respite from the terror that has indelibly colored their sex lives.

"I often say that I don't think gay men are having unprotected sex because they get high and drunk," Shults says. "They get high and drunk so they can have unprotected sex. I think the rigidity of these early efforts actually helped create barebackers, a subculture of men whose identity is defined in opposition to HIV prevention efforts."

He points to HIV testing as a good example. "Gay men have always been encouraged to get tested. But when we do, they tell us that the test is only semi-accurate unless we haven't had sex in the last six months — yeah, right — and that we should continue to use condoms as if we or our partners were infected. So then why get tested? What's the point if testing has no impact on how I live my sex life. This doesn't empower gay men, doesn't allow them to feel confident in their negative status, and offers no options for alternatives to using condoms forever just in case. Inherent in this approach is a fundamental sense of expandability surrounding gay sex. We don't tell straight people to use condoms forever just in case; it's laughable in fact to think we might."

This iusse isn't a new one for Shults and other gay men. In 1994 he delivered a speech at a Texas Department of Health Conference called "The Influence of Homophobia on HIV Prevention Targeted to Gay Men" that outlined a lot of these thoughts, he recalls.

He started doing comedy a couple of years ago as an outlet for his writing and views on things. Plus he loves to perform and act. He always loved the idea of being able to write for a straight audience to make fun of them, the way early black comics made fun of white people while generating discourse that contributed to social change. "I think stand-up is one of the most powerful tools for that sort of thing because it provides a place to talk and laugh about stuff that makes us all uncomfortable, and stuff about which most people are really ignorant. But its more palatable to people if a joke is structured well; it’s all about the writing. So I get obsessed with jokes, trying to make them work until I lose all objectivity."

break An astute student of stand-up, Shults offers, "Gay people still endure so much oppression. Even the most progressive and funny of comics get the gay stuff wrong. Jon Stewart called Nixon gay to insult him in an episode I saw only a few weeks ago. Bill Maher still makes fun of gays with the clichéd limp wrist and jokes about fashion — I don’t fault him for making fun of gays — I’d be madder if he didn’t — but they’re just not funny because things have changed, and most straight comics are out of touch. There are all kinds of sexual minorities, but people only see the most obvious of examples among us and assume we are all the same."

An astute student of stand-up, Shults offers, "Gay people still endure so much oppression. Even the most progressive and funny of comics get the gay stuff wrong. Jon Stewart called Nixon gay to insult him in an episode I saw only a few weeks ago. Bill Maher still makes fun of gays with the clichéd limp wrist and jokes about fashion — I don’t fault him for making fun of gays — I’d be madder if he didn’t — but they’re just not funny because things have changed, and most straight comics are out of touch. There are all kinds of sexual minorities, but people only see the most obvious of examples among us and assume we are all the same."

He points to one of his old punch lines: "Gays are like toupees; you only notice the obvious ones and the cheap ones."

"And I love these comics and watch them religiously," Shults says of straight progressive comics like Stewart. "But gay people have to just overlook so much ignorance, or translate mainstream representations into their experience while other folks just get to identify with most characters in TV and film. The best people are still really stupid about gay stuff. The fact that even Louis C.K. and Chris Rock defend the use of the word 'f****t' in their routines makes me so mad. I mean, can you imagine a white guy trying to justify using the n word liberally whenever they think it’s appropriate? So I like to write jokes about this stuff so I have a place to put the anger."

And he has a lot of anger. Take for example, TV shows like Modern Family and The New Normal, which seem so odd to Shults. "It feels like a form of blackface to have the actor who plays the character Cam — who is not gay in real life — parade and prance around for the amusement of other straight people. Also, how come they’re all obsessed with having babies and getting married? Is that the only way we are allowed any respect or legitimacy in the mainstream? To ape heterosexuals? I mean, these new shows make Will & Grace look like Game of Thrones!"

Shults, originally from New Orleans, moved to Texas (Corpus Christi first, and later Austin) after high school. He escaped the oppressive South, where he was both chronically terrified and turned on by Texas frat boys, and moved to San Francisco to be out, loud, and proud. He moved to New York City 10 years ago and says he's never leaving, which means the job opportunities are wide open. At the very least, Jon Stewart could desperately use Shults as his “senior gay correspondent.”

Shults feels that the slogan "Use a condom every time" is catchy but also vague and unrealistic. "People falter, and what's more, people place value in barrier-free sex," the comic turned activist says. "No one loves condoms; they love what condoms can do for them. But eventually gay men, just like straight people, look for ways to have more fulfilling sexual experiences, such as sex with a long-term partner who is also HIV-negative. But instead of addressing gay men's ambivalence about using condoms, prevention efforts shamed them for having such thoughts. When I was in my 20s, I thought having unprotected oral sex posed the same threat as unprotected anal sex. Rather than giving gay men the facts and explaining risk as a hierarchy and letting men come up with a risk portfolio that worked for them — having more oral sex over anal intercourse — prevention efforts suggested all sexual activities were equally risky. This type of black-and-white, all-or-nothing prevention strategy gives people two options: adhere or abandon hope for surviving."

Shults feels that the slogan "Use a condom every time" is catchy but also vague and unrealistic. "People falter, and what's more, people place value in barrier-free sex," the comic turned activist says. "No one loves condoms; they love what condoms can do for them. But eventually gay men, just like straight people, look for ways to have more fulfilling sexual experiences, such as sex with a long-term partner who is also HIV-negative. But instead of addressing gay men's ambivalence about using condoms, prevention efforts shamed them for having such thoughts. When I was in my 20s, I thought having unprotected oral sex posed the same threat as unprotected anal sex. Rather than giving gay men the facts and explaining risk as a hierarchy and letting men come up with a risk portfolio that worked for them — having more oral sex over anal intercourse — prevention efforts suggested all sexual activities were equally risky. This type of black-and-white, all-or-nothing prevention strategy gives people two options: adhere or abandon hope for surviving." An astute student of stand-up, Shults offers, "Gay people still endure so much oppression. Even the most progressive and funny of comics get the gay stuff wrong. Jon Stewart called Nixon gay to insult him in an episode I saw only a few weeks ago. Bill Maher still makes fun of gays with the clichéd limp wrist and jokes about fashion — I don’t fault him for making fun of gays — I’d be madder if he didn’t — but they’re just not funny because things have changed, and most straight comics are out of touch. There are all kinds of sexual minorities, but people only see the most obvious of examples among us and assume we are all the same."

An astute student of stand-up, Shults offers, "Gay people still endure so much oppression. Even the most progressive and funny of comics get the gay stuff wrong. Jon Stewart called Nixon gay to insult him in an episode I saw only a few weeks ago. Bill Maher still makes fun of gays with the clichéd limp wrist and jokes about fashion — I don’t fault him for making fun of gays — I’d be madder if he didn’t — but they’re just not funny because things have changed, and most straight comics are out of touch. There are all kinds of sexual minorities, but people only see the most obvious of examples among us and assume we are all the same."