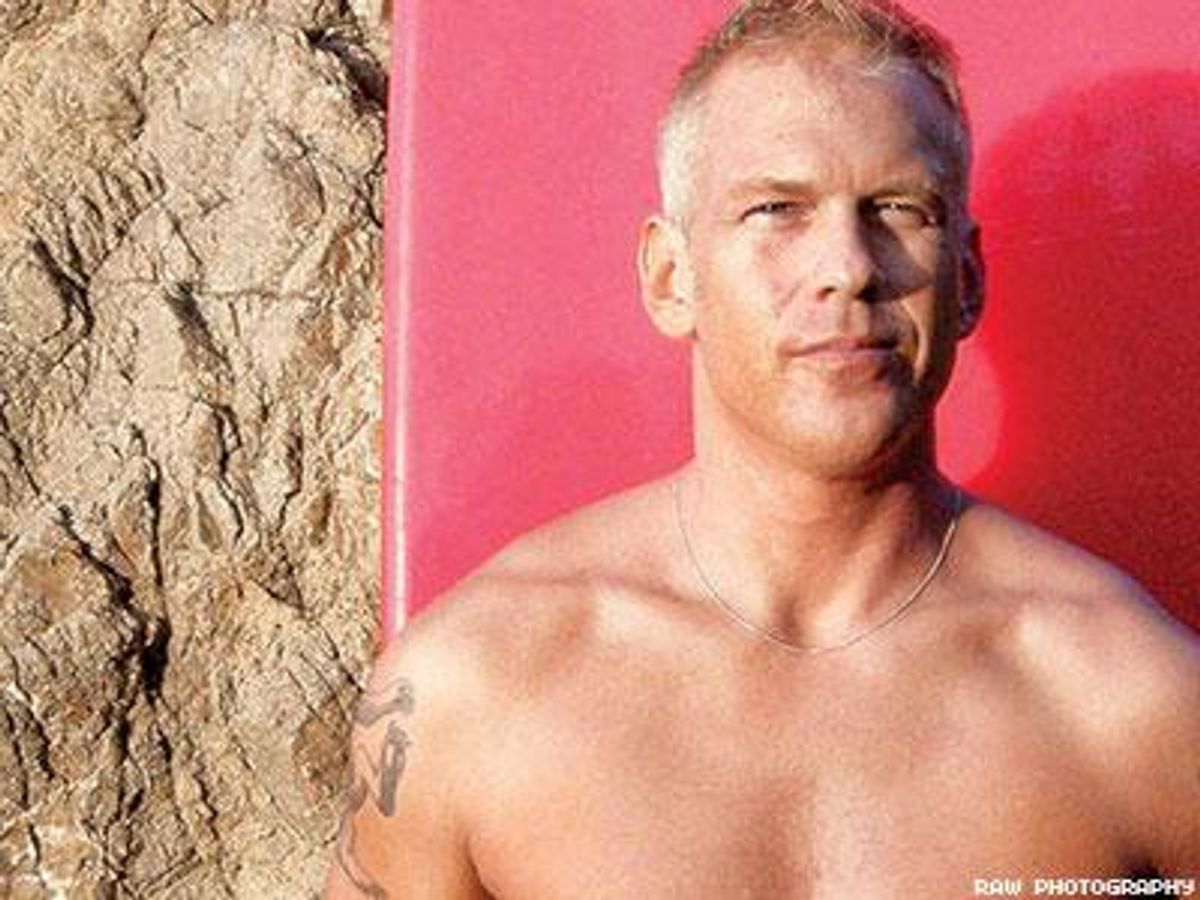

With his classic surfer looks and a positive focus, lifestyle expert Sam Page might look just like any other Southern California fitness buff. But with a celebrity clientele that includes Florence Welch, the woman behind the popular indie band Florence and the Machine, and a Zen-learner-meets-gay-Dr.-Oz philosophy, Page is anything but a typical Hollywood trainer (though he’s been courted by more than a few reality TV producers this year alone). That’s because the fitness guru doesn’t just work with Tinseltown elite. He’s been helping other HIV-positive guys, including members of Being Alive and Life Group LA, “reach a fitness level they desire” for a decade now. In fact, it’s that focus on what his clients desire that sets him apart. “I think it’s important for people to know that activity is not necessarily indicative of health, and being healthy is not wholly dependent upon one’s activity,” says Page. “Actually, true health is more like a complex ecosystem of many interdependent factors. When balanced, this ecosystem can reflect optimal wellness.”

Page, cofounded and published Hero, a short-lived but popular gay magazine that was forced out of business following the post-9/11 economic downturn, and has since turned his love of health and fitness into a serious lifestyle brand, turning his own HIV status into something powerful and impactful along the way.

What sparked your desire to not only transform your life but the lives and bodies of others?

First, I understand what it’s like to be overweight. I moved to Los Angeles at age 22 and was overwhelmed pretty quickly out of the gate by the amount of beautiful people here. The town probably attracts more people with universal appeal, but living in a sea of seeming perfection feels pretty isolating, and I found myself wanting to compensate for that. By the time most kids get their driver’s license, I had already owned and operated three retail candy and gift stores in my home state of Utah, where candy is practically a food group. Eating became a very natural place for me to seek solace. Then, after my magazine, Hero, went under, and my first long-term relationship ended, I went on a gay cruise to Mexico. There was a costume contest one night, which gets very competitive. A group of guys from San Diego had brought back beautiful handmade beaded necklaces and headdresses from Hawaii. They approached me and asked me if I wanted to dress up and join the group of hula dancers. Delighted and flattered, I said yes. That night, shirtless with just laurels on our heads and grass skirts around our waists, 20 gay brothers stood together, toe to toe, at the top of the ocean liner, overlooking the crowd. That was a life-changing moment for me.

When did you find out you were HIV-positive?

So My diagnosis is a cautionary tale. I found out in 2003. I’d been single and was modeling and acting. I’d just landed a magazine cover, had just finished filming with [Quinceañera director] Wash West, and was traveling around the country dancing, at Stonewall in New York, at Cherry’s on Fire Island, and in Miami–Fort Lauderdale. My friend and I went into West Hollywood for a free HIV test at one of the clinics. We both tested negative. I remember high-fiving each other in relief.

But that wasn’t the end of the story.

Yes, imagine my shock when less than a week later, I wake up one morning unable to form coherent sentences; instead I’m talking in what sounds like my own personal language. I had no idea that I was not making sense, but my friend did, so he took me to Cedars-Sinai [a hospital in Los Angeles]. At the emergency room, I couldn’t even fill out the patient information form they gave me. Diagnosis? Viral meningitis “probably caused by HIV,” but the doctor couldn’t be sure without a viral load count. He ended up being right: I was HIV-positive, just hadn’t created any antibodies yet.

After testing negative, that must have been a shock.

A negative HIV antibody test is really just a false sense of security. This is something I try to educate people about, especially guys online who say they’re HIV-negative. You absolutely can test negative while, in reality, not only are you unknowingly HIV-positive, but you’re also incredibly contagious. The danger of HIV is not in the disclosing, med-taking set of people out there. I wasn’t hooking up with people who said, “Hey, man, just so you know, I’m HIV-positive and undetectable.” I actively steered away from those people. The clear and present is with guys who don’t really know their status — who say they’re negative and practice unsafe sex.

What was one of your biggest challenges?

I really struggled with shame. I didn’t know how or when to talk about my HIV status. I developed strong feelings for someone, so I uprooted my life and moved across the country. But because I did not disclose my status when we first met, we had a trust gap and the relationship never had a chance. Before I moved back to Los Angeles, I was invited to be the lead of a stage play in Austin at the Hyde Park Theatre. That time in Austin, working with those actors, all of us dealing with some issue or another — well, I’ll just say that art, like music, is powerful and can be a very healing modality in our lives.

Did anyone’s reaction really impact you?

After 15-plus months being single and dating a few serodiscordant guys, I faced a lot of stigma and felt ashamed. But there was this one guy I really liked in particular, who I’d met a few years before. He was HIV-negative, and I couldn’t bear any more heartbreak or rejection, so I decided to put it all out there, telling him my HIV status via instant message in advance of our first dinner date. He seemed so completely unfazed that I remember his exact words: “I don’t mind you’re positive, as long as you don’t mind that I’m negative,” he typed, without missing a beat.

You’ve used your popularity to fight HIV stigma as well.

What popularity? [Laughs] Well, in my career as an athletic trainer, I’ve never made my status a secret. Often clients have their own curiosities about HIV, so on an individual level, I try to help them understand. I wrote about HIV and fitness for Being Alive’s newsletter in Los Angeles for several years and spoke at their annual Spirit of Hope Awards in 2007. There was a dearth of information about HIV and fitness when I started writing on the topic in 2003, painfully little information. I just felt called to doing it, because it needed to be done.

In your previous profession, you were a magazine publisher.

We launched Hero the same year Steve Jobs introduced the iMac. I didn’t see myself reflected in the other magazines at the time, but my cofounder and I knew a lot people who expressed interest in our idea of “a magazine for the rest of us,” which became the tagline. Other big magazine editors tried to warn me, but you never really understand what a huge, complex undertaking is it is to publish a national magazine until you do it. My parents raised me to believe you can do anything you put your mind to, as long as you don’t quit. I still — mostly — believe that. Publishing Hero was part exercise and part activism: exercise because it helped me more fully accept myself as gay, and activism because even though the original intention was to transcend sexual activism and politics, it’s clear now that Hero was a physical manifestation of precisely those very things — a sign of the times. To borrow an expression from my forthcoming book, Surfing With God, we were “standing on the surfboards of giants” at the very front of a tidal wave that would wash across the world, making gay culture mainstream.