A middle-aged African- American woman, with her long hair braided down her back, juts up from the audience with one declarative statement that has everyone around her nodding vigorously: “We’re dying in the South.”

It’s the first day of the 18th Annual United States Conference on AIDS in San Diego, and it’s standing room only at the enormously popular panel discussion “Black Gay Men: Where Are We Now? Where Do We Need to Be?”

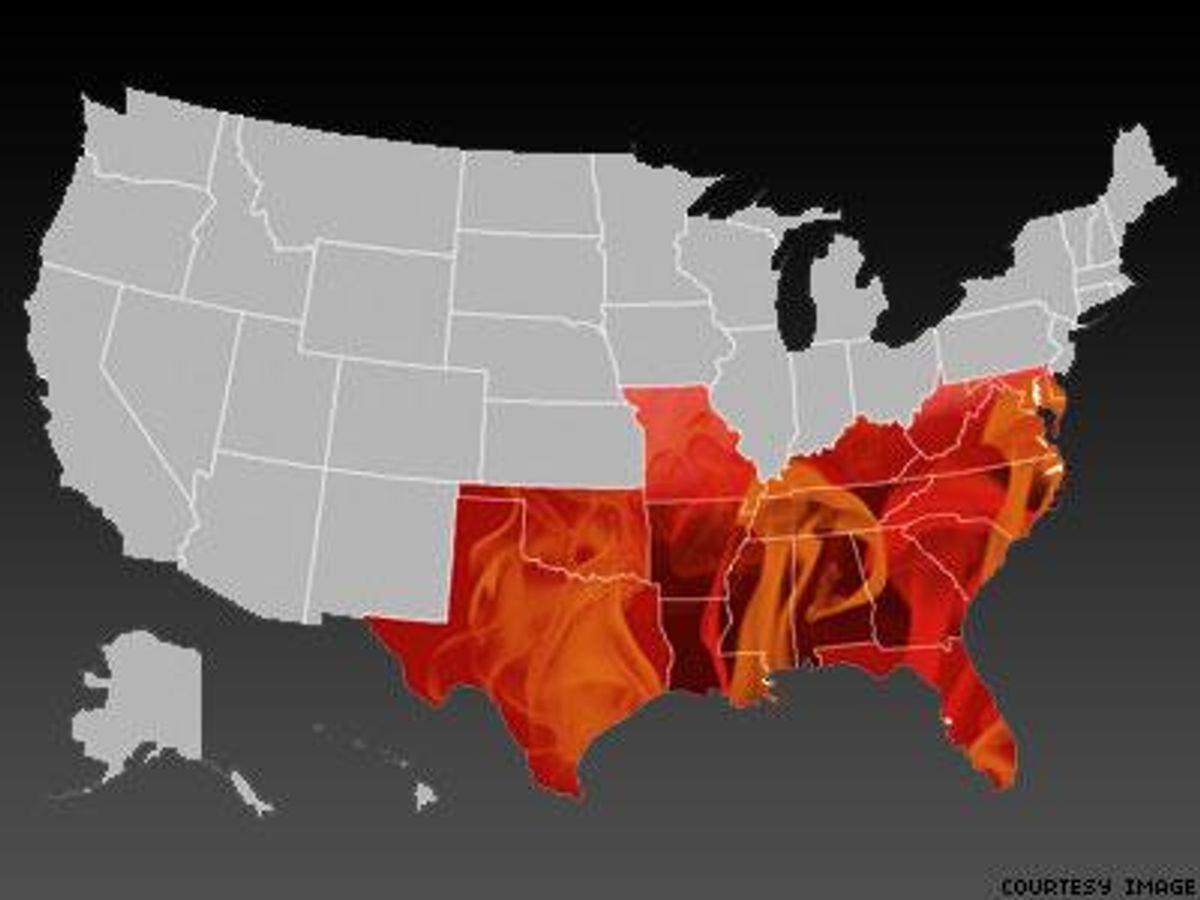

The panelists have just wrapped their recommendations when the woman stands and delivers her pronouncement and encapsulates what I will hear all week, at panels, workshops, and plenary sessions, even in conversations overheard in the halls or walking by the waterfront outside the San Diego Hilton. Among HIV activists, health care workers, and people living with HIV or AIDS, there’s a pervasive sense of exhaustion that colors nearly every conversation about the epidemic of HIV in the South, a region that, sadly, boasts the country’s highest number of HIV cases—and of deaths from complications of AIDS.

As Ebola — a disease that, as of going to press, had been verified as the cause of one death in this country — dominates newscasts around the country, few mainstream media outlets even bother covering HIV or AIDS anymore. But it still claims the lives of more than 15,500 Americans each year.

Why are Americans fixated on an epidemic that is half a world away rather than on the epidemic ravaging southern states on our own shores? Is it because the disproportionate number of Americans dying of HIV-related conditions are African-American?

That’s what southern activists and providers want to know. The sense of being ignored or invisible punctuates their conversations. “We can’t get people to notice or cover what’s happening in the South,” adds the woman who has our rapt attention, and whose name I didn’t catch. Even an article in a special South-focused issue of HIV Specialist says of the virus in the area “Call 911! There is an emergency and no one has answered our call.”

Sure, things are better than the early days of the epidemic, and recent medical and pharmaceutical breakthroughs have dramatically increased the longevity of those who can access treatment. But those same breakthroughs may have lulled many into the mistaken impression that HIV is no longer a threat.

People are still dying of AIDS complications, especially in the South. “Blacks/African Americans continue to experience the most severe burden of HIV,” says the Centers for Disease Control. Although they represent only 12 percent of the population, black Americans account for nearly half of all deaths from AIDS complications annually.

“We are racing against time — and AIDS — to avoid becoming a people that once was,” said HIV-positive activist, journalist, and artist Keith Green, a former associate editor of Positively Aware, who cofounded the Chicago Black Gay Men’s Caucus, led a research project on PrEP, and was director of federal affairs at AIDS Foundation of Chicago. “Whether positive or negative, black gay men live with HIV each day of our lives.”

The same can be said for many African-American women and men living in these nine Southern states—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Tennessee. Residents of these states are particularly vulnerable: Although they make up only 22 percent of the total U.S. population, they represent nearly 32 percent of new HIV diagnoses.

So why are blacks in the South bearing the brunt of the current HIV epidemic? The reasons are as varied as the ingredients in a creole gumbo, and they have been stewing for a very, very long time.

The hostilities and inequalities currently shackling African-Americans can trace their ancestry to the days before the Civil War. We may be long past the time when the Southern economy was built on the backs of slaves, but those dark days have a long legacy, reaching through time to create sociopolitical and economic inequities and explain why African-Americans are suspicious of participating in clinical trials. (Google “Tuskegee syphilis experiment” if you think this suspicion is historically baseless.)

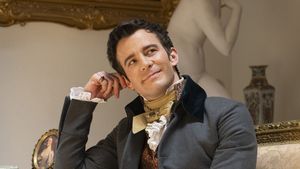

Dr. Michelle Collins-Ogle (right)

Dr. Michelle Collins-Ogle (right)

Michelle Collins-Ogle, MD, is familiar with those factors. At North Carolina’s Warren-Vance Community Clinic, most of her patients are dealing directly with at least one of these issues. Around 50 percent of the population in the clinic’s service area lives below the poverty level, and the median family income for a person living with HIV in Vance County is $15,000.

Collins-Ogle says she was aware of her patients’ struggles to access food and housing security, and she knew that many of them also lacked consistent telephone service and full plumbing. Still, she was surprised at the way these problems would affect her HIV-positive patients’ ability to adhere to their medical treatment plans. One patient, for example, had been seeing her regularly, but his CD4-cell counts were still low and he had seen only a very small decrease in his viral load. Collins-Ogle was stumped—until staff of the free clinic conducted a home visit. There they discovered that the patient lived in a food desert (the only store in the community that sold food was a gas station) and had no access to transportation. Further examining the small quarters he called home, they realized something was missing: a refrigerator.

The ritonavir gel capsules the patient was prescribed required refrigeration. In the blistering southern heat, the gelcaps had melted together so he couldn’t take them with his protease inhibitor and thus wasn’t seeing the boosting effect.

“He was not intentionally non-adherent to his treatment plan,” Collins-Ogle later wrote for HIV Specialist. “His life circumstances and socioeconomic condition prevented him from being able to keep his HIV in control.”

Those socioeconomic conditions prevent many HIV-positive Southerners, particularly if they are African-American, from seeing positive health outcomes.

According to the Census, since 2000 the poverty rate in the South has increased; rising from an already devastating 21 million people, or 22 percent of the population, living in poverty to 34 million, or 31 percent, in 2010. Meanwhile, illiteracy rates hover between 15 and 20 percent in Southern states (with Texas and Florida battling for the highest percentage of residents lacking basic prose literacy skills). When patients can’t understand their medication or treatment instructions, they are less likely to follow them as prescribed.

Poverty and illiteracy also contribute to another vicious cycle: the number of African-American men incarcerated in American prisons. If current incarceration trends continue, one in every three black males born today can expect to go to prison at some point in their life, compared with one in every six Latino males, and one in every 17 white males, according to a recent report by the Sentencing Project.

The Washington, D.C.-based organization, which advocates for prison reform, noted as much in its 2013 Report of the Sentencing Project to the United Nations Human Rights Committee Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System, saying that racial minorities are more likely than white Americans to be arrested and “once arrested, they are more likely to be convicted; and once convicted, they are more likely to face stiff sentences.”

HIV criminalization also disproportionately affects those in the South, says Rashida Richardson of the Center for HIV Law and Policy.

“Criminalization is a major issue for gay black men in the South because it lies at the intersection of forces that affect this demographic,” she says, including the disproportionate number of black men being incarcerated and the health disparities African-Americans face when it comes to HIV.

Richardson also points out that with HIV criminalization statutes, “gay and transgender youth who end up in the justice system are at risk of being labeled sex offenders, regardless of whether they have actually committed” a sex crime.

The health disparities that Richardson also points to are very real and have very negative consequences. According to a 2012 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention fact sheet, many African-Americans with HIV are unlikely to be in ongoing care or to have their virus under control. Of all African-Americans with HIV, 81 percent have been diagnosed and 62 percent linked to care, but only 34 percent remain in regular care and even fewer (29 percent) are on antiretroviral medication. As a result, only one in five HIV-positive African-Americans are virally suppressed, compared to one in three Caucasians.

These statistics add up to a disturbing result: HIV-positive African-Americans are more likely to die from AIDS-related causes. Although black people make up only 12 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 56 percent of all deaths due to HIV or AIDS complications in 2009. And their survival time after getting an AIDS diagnosis is also lower on average, compared to other racial/ethnic groups, according to a 2013 CDC report.

The lack of access to medical care is one of the biggest hindrances to positive health outcomes for those in the South. Although the HIV epidemic continues to ravage populations in the South, politicians in eight out of nine states of that make up the Deep South have refused to expand Medicaid or take advantage of federal funding available as part of the Affordable Care Act.

“All of our advancements mean nothing if we can’t engage people in care,” notes Leo Moore, MD, an internal medicine resident at the Yale University School of Medicine speaking at the U.S. Conference on AIDS.

From the perspectives of some Southern activists, discussions about the moral implications of using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are frivolous. Health care workers and HIV activists alike are quick to point out that those fighting the disease in the South generally don’t have the luxury to consider prevention efforts like PReP. Again, that rousing woman at the conference: “We can’t get folks on medication who are positive, let alone negative,” she said, before concluding, “We can’t get people to see a doctor.”

Poverty and a lack of health insurance play a big role in preventing HIV-positive individuals from accessing care. But so does stigma.

In fact, activists say stigma has an enormous impact on why HIV has had such a devastating impact on the American South. Stigma—and the Bible Belt.

Both “institutional and community-level stigma have impeded the development of potentially effective, culturally-tailored HIV testing and prevention interventions,” says a report from the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and the National Coalition of STD Directors.

Collins-Ogle agrees, noting in her HIV Specialist article that religious conservatives “prohibit our southern residents from speaking openly about sexual topics, including birth control and condom use.” She continues, “The Bible is used to spout bigotry. … The net effect of this hypocrisy is the inability of [LGBT and HIV-positive people] to gain employment, housing, and access to care.”

Although the religious persecution in Bible Belt states is disproportionately wielded against gay and bisexual men and women and transgender or gender-variant people, those who are HIV-positive are certainly close behind.

On Our America With Lisa Ling’s “Black America’s Silent Epidemic,” Daphne Rogers — who later became an HIV medical case manager at Washington, D.C.-based Women’s Collective —admitted to initially walking three blocks out of her way to avoid being seen entering the back door of an HIV clinic. Another woman, Kimberly Sparrow, who found out she was positive when her new husband suddenly became gravely ill (he later died), talked about being ostracized by her church’s congregation after she came out about her HIV status. In particular, she noticed that people avoided physical contact with her. It’s a story all too common for people who learn they have HIV.

What are the Solutions?

The forces driving HIV in the South are diverse—and the solutions to the problem may need to be as multifaceted.

The Southern HIV/AIDS Strategic Strategy Initiative called for a “holistic approach” in its 2014 report HIV/AIDS in the Southern U.S.: Trends from 2008-2011 Show Consistent, Disproportionate Epidemic. Such an approach, it says, must “address the multiple factors that contribute to the disproportionate epidemic in the South, such as lack of resources and regional resource inequalities as well as stigma and high STI rates.”

Meet Them Where They Are

Connecting Resources for Urban Sexual Health, better known among activists as CRUSH, is a consortium of agencies and organizations in Alameda County, Calif., on the verge of issuing similar recommendations based on its study and treatment program for young men of color who have sex with men. Its study concluded that many young gay and bi men of color could benefit from mental health counseling, that money is still a barrier to medication, and that those agencies serving people of color need to meet their clients where they are. For example, when the member agencies learned that many of their clients had no stable address or phone number, they relied on email communications (because most clients were accessing free email via friends or public libraries). And when several clients admitted they had skipped pills when out partying or spending the night away from home, CRUSH began distributing a keychain capable of discreetly carrying their medication.

Opt-Out Testing

Some young black gay men have other ideas for how to stem the tide of HIV infections and how to get those who are poz into treatment. One popular idea is fighting for greater adoption of the “opt-out” HIV testing model that the CDC recommended in 2006, where doctors routinely offer HIV testing to all their patients at each contact, so that the client has to actively choose not to get the screening.

A 2010 study found that the model had met with only moderate success when it was adopted by a large emergency medicine department. In fact, 75 percent of the patients chose not to get the test, probably because they did not think they were at risk for HIV, said Jason Haukoos, MD, of Denver Health Medical Center.

However, the model has not been given a fair trial in primary care environments where a patient might feel more comfortable and the doctor could explain the rationale for everyone to have the test just as they would a pap smear or prostate exam—neither of which anyone particularly enjoys, but which most patients still do.

But activists like Kenyon Farrow, former executive director of Queers for Economic Justice, maintains that testing is just one aspect of a broken system. “Testing is great, but what about voter registration, electoral politics?” he says. Farrow argues that HIV infection rates in the South cannot be adequately attacked without addressing other social justice and economic inequality issues. He and other activists argue that organizations addressing HIV need to be “reimagined” as broader social justice agencies aiming to address deeper sociocultural issues.

Telemedicine in Rural Communities

HIV-positive residents in the rural south may benefit from strategies like the telemedicine program from Medical AIDS Outreach of Alabama. As part of AIDS United’s Access to Care initiative under the Social Innovation Fund, MAO set up locations in rural Alabama where patients with no HIV medicine providers nearby can talk with doctors via high-definition video screens. So far the program has a 92 percent patient retention rate, and it has received recognition at several White House events in the past year. Since it was launched in 2011, the program has proven a cost-effective way of giving rural populations access to HIV care.

According to an article in Positively Aware, some of the telemedicine patients eagerly await their appointments. “We have several clients who always dress up for the camera. … They love being on camera,” Michael Murphree, the CEO of MAO told the magazine. “One of the guys admits that for him, it’s his American Idol moment. He never misses an appointment.”

Now the agency has received a $1.2 million grant to establish more telemedicine connections in remote areas of Alabama hardest hit by HIV. (The group used AIDS Vu maps to pinpoint prime locations.) This program could be adapted to other states and regions, though Medical AIDS United staffers warn they had to first convince the Alabama Board of Medical Examiners to accept telemedicine as a viable method of providing care.

Activist Aquarius Gilmer (left)

Activist Aquarius Gilmer (left)

Faith Leaders Combating Stigma & Misinformation

A study by the HIV Vaccine Research Initiative determined that many African-Americans are hesitant to participate in vaccine trials for three reasons: Some believe that an HIV cure or vaccine already exists but is being withheld from their population; others fear stigma and discrimination if they were known to be participating in a vaccine trial; and still others are concerned about whether blacks would even have access to a vaccine if one was were developed.

Since the study also found that African-Americans are more likely than other groups to see faith leaders as advisers whose guidance and information can be trusted, it recommends building collaborations with clergy and other religious leaders who provide information, inspiration, and mobilization within the black community.

HIV activist—and trained preacher—Aquarius Gilmer agrees. A regional affiliate coordinator at the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS, Gilmer says his organization is just starting to work closely with seminaries to that end: “We’re working with seminaries around the country to educate this next generation of black pastors to not only talk about HIV and stigma but…to be advocates from behind the pulpit, and also to equip their congregations to be advocates for their own family members, or their own neighbors.”

Although Gilmer says the program is just in the planning stage (and is still seeking financial support), his group hopes to roll it out next year by attending several black church studies conferences.

Gilmer also says that engaging HIV-negative people in the conversation about ending HIV is essential, “particularly because they can help us tremendously in curbing stigma. We know stigma really fuels this epidemic, so if we had more allies, that would really help our cause.” He adds, “And vice versa, if people who are in HIV policy could think about how to provide people services who are HIV-negative. Because we are also hearing about men who are HIV-negative feeling stigma for being negative but who also don’t have access to services because they are negative.”

PrEP could play a role in this too. After all, Gilmer reasons, if HIV-positive and HIV-negative are both taking a daily pill to retain their health, it would reduce stigma around HIV care.

Meanwhile, Farrow calls on the residents of Southern states to push for Medicaid expansion and demand to be enrolled because they are already paying for the federal programs. Of course, Gilmer adds, African-Americans are still trying to figure out how to protest in “a police state where you can get shot with your hands up.”

Mental health issues of African-Americans—especially those who are gay or HIV-positive—also need to be addressed. According to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, suicide is the third leading cause of death among young black men.

CRUSH studied young gay and bisexual men of color in Alameda County and discovered that many of its member agencies’ clients—who were generally HIV-negative—could benefit from counseling for the stigma they’d been subjected to simply for having sex with men.

Atlanta’s Men’s Information Services: Testing, Empowerment, Resources has taken the “holistic” strategy to heart, implementing a program that offers a variety of free services to gay and bi men, including STI testing, meditation, yoga, sexual health education, support groups, and a year of free mental health counseling for any issue.

So Will the South Rise to the Challenge? Perhaps a more important question is whether the rest of the country will. HIV does not exist in a vacuum, and the solution to rising rates and lack of treatment in any region depends in part on the others. If LGBT and HIV activists as well as organizations, politicians, and health care leaders in other parts of the nation became more aware of and determined to resolve the issues around HIV and AIDS in the South, there is still hope for a solution. If, instead, those of us outside the South ignore the problem and pretend all is well, we may live long and prosper ourselves, but we will have blood on our hands.

Stay tuned: To read more about HIV among black gay and bi men, pick up the Jan/Feb 2015 issue of HIV Plus magazine.

Dr. Michelle Collins-Ogle (right)

Dr. Michelle Collins-Ogle (right) Activist Aquarius Gilmer (left)

Activist Aquarius Gilmer (left)