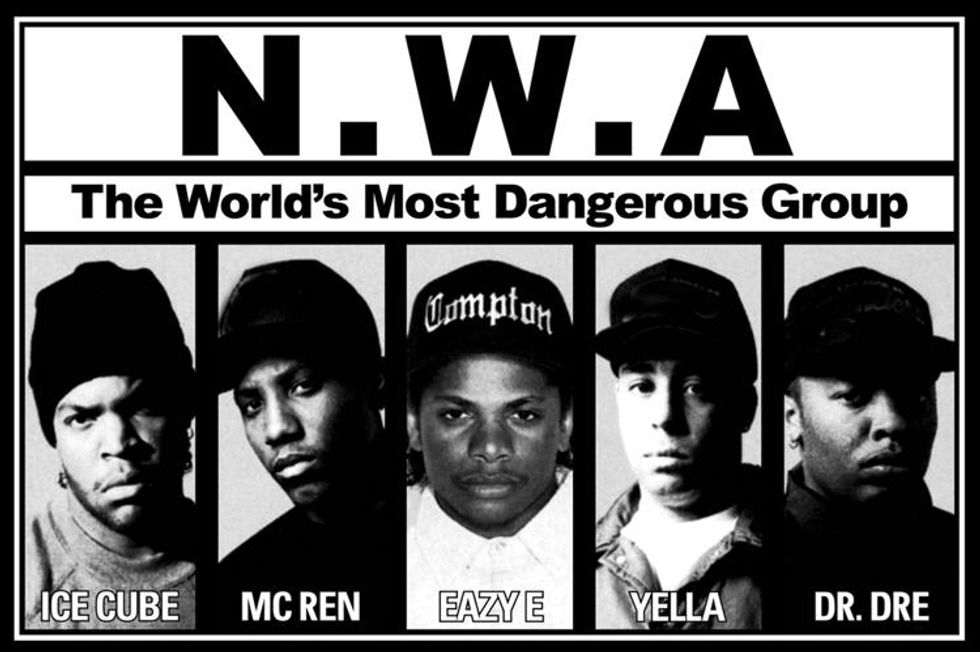

Straight Outta Compton, which is just out on DVD and Blu-ray, has much to offer its audiences. There’s music, drama, stellar performances from a diverse cast, and a message about racism, oppression, and police violence that resonates with the modern-day Black Lives Matter movement.

But for Eric Wright Jr., the son of the late rapper Eazy-E, whose life and death were depicted in the film, the most important part of Straight Outta Compton was a letter with an important message that was delivered to fans at a press conference.

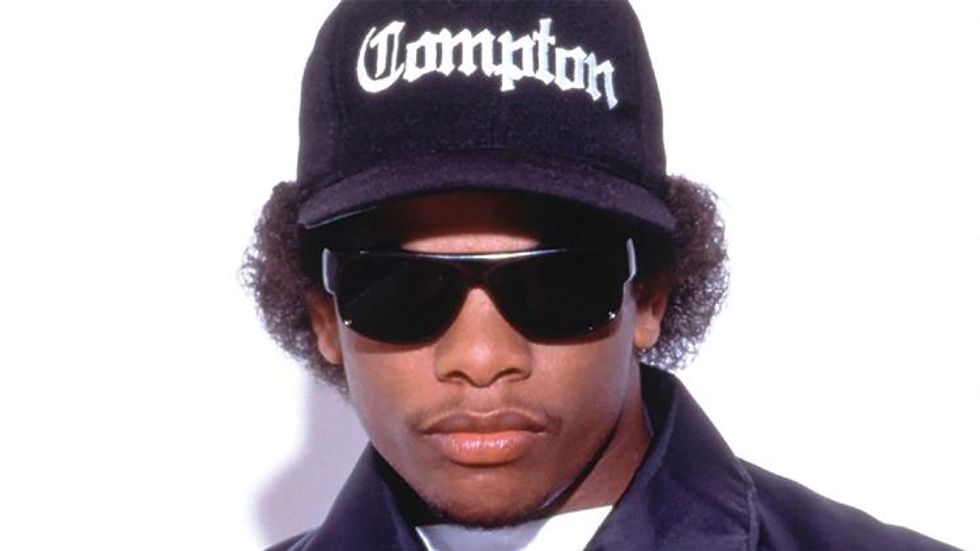

“I just feel that I’ve got thousands and thousands of young fans that have to learn about what’s real when it comes to AIDS,” Eazy-E said in the letter released just a few days before his death, which came from an AIDS-related illness on March 26, 1995. “Like the others before me, I would like to turn my own problem into something good that will reach out to all my homeboys and their kin. Because I want to save their asses before it’s too late.”

The letter was a game-changing moment for the country. At the time, HIV was perceived as a white gay man’s illness, and Eazy-E, a black rapper who identified as straight, helped shatter that misperception. He reminded the world that it is a disease that affects everyone. That he died just weeks after his diagnosis, and that he remains the only hip-hop artist with his level of fame to have come out as HIV-positive, makes his act that much more groundbreaking.

“That speech and that letter was a key point for individuals in the urban community to say, ‘Wow.… It happened to this individual, who people feel was like a legend, an icon. It can happen to us all,’” says his son, who made a decision in his early 20s to take on his father’s cause and become an HIV activist. Wright is also a rapper, who goes by the stage name Lil Eazy-E.

Unfortunately, more than 20 years have passed since Eazy-E’s letter, and HIV is still a crisis among African-Americans. In fact, it is the racial/ethnic group most affected by the virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that African-Americans account for 44 percent of new infections. Although gay and bisexual men in this group bear the heaviest burden — six in 10 will be HIV-positive by the age of 40 — the rate of HIV new infections among African-American women is still 20 times higher than that of white women, and black men in general also have much higher rates than other demographics.

But Straight Outta Compton has given the rapper’s words of warning another chance to reach this population. His son praised the film for repeating his father’s message, pointing to the thousands of people who saw the movie who may have never heard it, or were too young to process it, when it was broadcast on live television in 1995.

HIV organizations have recognized the opportunity the movie presented to reignite conversations about safe sex and testing in at-risk communities. The Black AIDS Institute, which in the past has worked with Wright on public service announcements and initiatives like its

“Test 1 Million” campaign, saw an immediate response from audience members.

“We certainly got a lot of calls from folks who saw the movie, and had not previously been aware of that part of the storyline,” says Phill Wilson, the organization’s CEO. “What we are hoping and what we are working on is to see if the film might be an opportunity…in getting the hip-hop community more involved in the HIV/AIDS issue.”

“It’s a part of a larger conversation that’s already going on in black communities,” he says, noting the 125 black-owned newspapers and the 500 black-owned radio stations that are all addressing HIV and AIDS. Even the Black Lives Matter movement has expanded recently to incorporate health disparities such as the high rate

of HIV. “What the movie does, it continues a narrative that’s already there.”

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit, saw the marketing potential for Straight Outta Compton to amplify this narrative. The group posted signs that read “StraightOuttaCondoms” on billboards and park benches in Los Angeles around the time of the film’s release last August. It also created a public service announcement, “Real Talk,” that screened in over 80 theaters in Los Angeles, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C., which showed a black father and son having a frank discussion about condom use.

The campaign was a success that generated an “overwhelmingly positive response” from L.A. residents, who snapped photos that they shared on social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, says Christopher Johnson, AHF’s associate director of communications.

“It was a fun, quick campaign around one of the most successful movies of the year, it seemed to bring a smile or laugh to people’s faces regardless of their race, and it drove an increase of people seeking information on STDs and treatment locations to our websites,” Johnson says. “At the very least, the ‘StraightOuttaCondoms’ campaign underscores the knowledge we now have about AIDS and the continued importance of protecting oneself through consistent condom usage.”

Others, however, worry that the message has not hit home to the audience members who may be most at risk.

Gerrick Kennedy, a music reporter for the Los Angeles Times, praises Straight Outta Compton for its handling of Eazy-E’s diagnosis and death, but has his doubts about how much it raised HIV awareness.

“Out of everything in the film, I think that was handled with the most dignity, but also with the most truth,” he says, lauding the film for “showing exactly how quick it was, the fact that his friends struggled with it, the fact that his fans really struggled with it.”

In the film, Eazy-E has a frank conversation with his doctor about his diagnosis. It also shows the reaction of his wife, who flees the room, leaving him alone to register the shock. The rapper’s last words are those from his letter.

“I thought that was such a brave thing that he did,” Kennedy says of Eazy-E’s parting words. “It really lit a fire” of controversy, he adds, because it upended the stereotype of who was likely to contract the virus. This had led to endless speculation about the rapper’s sexual orientation or conspiracy theories that he may have been infected purposefully with a needle, which continue to this day.

But while the rumors still swirl — recently, the rapper Frost swore that Eazy-E contracted HIV through tainted acupuncture needles — Kennedy, who as a reporter keeps his ear to the ground on social and other media, says the HIV “conversation didn’t reignite” in the way it did for other hot-button topics related to the portrayal of the N.W.A. hip-hop group, such as violence and misogyny. It bothered him that there was so little talk about health.

He points to stigma, a lack of education about safe sex and testing, and an absence of black public figures who are vocal about HIV issues (or out about being positive) in the black and hip-hop worlds as possible reasons for this silence. After all, it is hard to have a conversation about a topic that many public figures and influencers do not talk about.

“It takes more visibility,” Kennedy says frankly. “How many people only started caring about trans women once Caitlyn [Jenner] came out? That’s just the reality we live in.”

Wright is working to address these issues of visibility. He is touring the country to talk to young people about safe sex and STD testing. He also stresses the importance of sex education in schools, particularly in urban and minority communities.

“Don’t be scared to get tested,” he tells young people. And to educators, he says, “Let them know [HIV] is not a scare tactic.”

As a musician and also as the son of a world-famous rapper who died of an AIDS-related illness, Wright is in a unique position to talk to young people about HIV and its causes. With him, “they open their ears and listen,” he says.

“We, as entertainers, do have a voice, a lot more than the news, a lot more than the newspapers, a lot more than politicians,” he acknowledges, placing a responsibility on other entertainers to recognize the power they have to influence the decisions of young people when it comes to issues like safe sex and HIV. “They have their attention and they have their ear.”

And when he finally releases his debut album, he looks forward to reaching more ears and sharing his own journey with the world.

“They can finally get what they were waiting for,” he concludes, “my story, of being my father’s son.” <

To help Lil Eazy-E in finding a cure for HIV, he asks that you please donate and/or volunteer at any of the AIDS organizations in your region. To bring Lil Eazy-E to speak at your schools or community centers, contact nwaent1@gmail.com for available dates.

Images: Roobcio/Queezz and Bukley/Shutterstock; NWA Entertainment; Reda Photography; Fifou; Peter Brooker; Rex Features/AP