Victoria Noe may have arrived at the front lines via a circuitous route, but, like other straight women fighting in the early battles of HIV, she was determined to do something significant during those darkest of days when the deadly epidemic raged — and most Americans gave little more than a shrug.

“I knew I did not want to look back on that time and realize that I hadn’t done a damn thing,” says Noe, the author of the critically acclaimed self-help Friend Grief series, about coping with the death of friends. She’s also the author of Fag Hags, Divas and Moms: The Legacy of Straight Women in the AIDS Community, an effort to bring recognition to the heterosexual women who fought HIV in those early days.

Noe went from fundraising for the Chicago arts community to working almost exclusively with AIDS service organizations. And she wasn’t alone. Of course, some straight women were themselves impacted by the disease while others were driven by grief over the loss of a loved one to AIDS complications. Others simply saw a need to join the fight. The most visible of these early contributors were Elizabeth Taylor and Princess Diana.

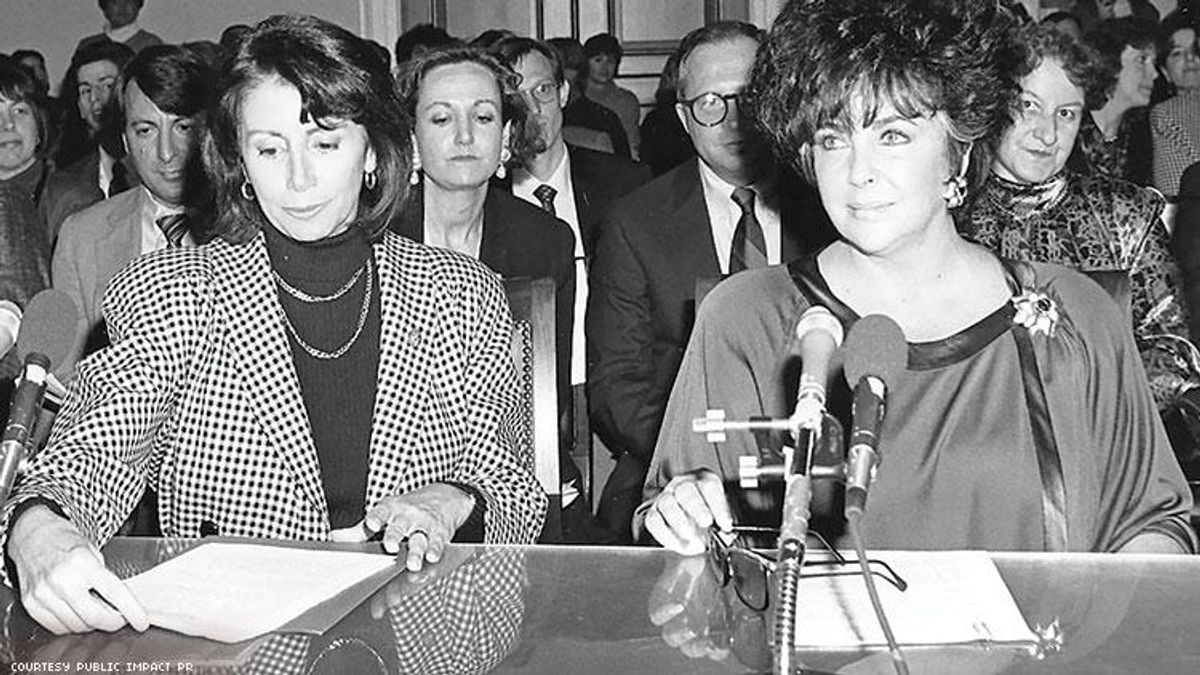

Taylor was perhaps the most famous actress of her time when she got involved in funding and supporting HIV research. Diana was one of the most beloved women in the world when she became a self-appointed HIV ambassador. Both women famously shook hands with people dying of AIDS. News outlets around the world featured photos of them not wearing gloves — immediately combating stigmas against touching people living with HIV.

“I think it’s hard for people in 2019 to understand not just the importance of their involvement in the early days of the epidemic, but what they were risking,” Noe explains. “They were arguably the two most recognizable women in the world — and they had nothing to gain with their involvement — but both decided to leverage their celebrity status to do something that could change the world.”

Above left: Dr Mathilde Krim with Mr. Leather. Right: Krishna Stone.

Another woman who helped do that was Dr. Mathilde Krim, a researcher at the Sloan-Kettering Institute in New York City who founded the AIDS Medical Foundation, which later merged with the National AIDS Research Foundation to become the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). Krim became the honorary “mom” of many poz gay men.

Homophobia and ignorance around the virus also made it difficult for survivors to grieve. “The people who were dying — mostly gay men at that time — were close to us,” Noe remembers. “We could grieve with others in the AIDS community, but if we mentioned what we were going through to someone on the outside, the reaction could be hateful.”

In many ways it was this hateful response that transformed grieving mothers into some of the most driven early fighters. “All of them shared one trait: They deeply loved their sons,” the writer says. “And when your child is sick or dying, you will fight anyone and everyone to help them.”

In Fag Hags, Divas and Moms, Noe introduces mothers like Willie Barrow (below), an ordained minister who marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; after losing her son to AIDS, she turned that same passion to the fight for people living with HIV. Another is Trudy James, who (when churches refused funerals to those who died of AIDS), created a “buddy program” through the Regional AIDS Interfaith Network in Arkansas to connect poz folks with volunteers recruited by churches.

Above right: Rev. Willie Barrow gives an impassioned speech

During one 11-week stretch, Noe lost a friend every week to AIDS. “The deaths were just relentless,” she recalls. The last was the cruelest of all for her personally: Steve Showalter, her assistant. Though Noe took time off of work, she didn’t stay away long. “When you’re in a state of war — because that’s what it always felt like to me — you don’t have the luxury to stop and take the time to grieve.”

Noe is the first to say that the women depicted in the book weren’t driven by a hope for recognition. They were doing it because of the need to honor their children, or because it was the right thing to do. While much of the spotlight has focused on the male-dominated activism of the time, Noe’s book reminds us there were plenty of straight women in the trenches too.