As New York City became the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, the theater community responded swiftly. In March, Broadway and many off-Broadway theaters announced they were suspending shows as a safety precaution, even before the city mandated such closures, leaving many actors and artists like Javier Muñoz out of a job.

The actor had just opened off-Broadway in Stephen Lloyd Helper’s play A Sign of the Times when he learned it would close due to the outbreak. While the news wasn’t easy to accept, Muñoz found a way to make lemonade out of the sour situation.

Alongside Jeff Whiting, owner of Open Jar Studios in midtown Manhattan, and Molly Braverman, director of Broadway Green Alliance, an industry-wide initiative encouraging the theater community to implement more environmentally friendly practices, Muñoz co-created the Broadway Relief Project. The project has put Broadway seamstresses, actors, and other theater artists to work creating surgical gowns and other personal protective equipment the local government requested in March. To date, it has recruited over 600 volunteers statewide.

“There were so many people who were already trying to implement their own efforts,” Muñoz says of the COVID-19 response in the city. “So instead of having five, six, seven efforts going at the same time, [I thought], Why don’t we all join together and make one Broadway effort? One big umbrella to house all of us and do it together.”

Muñoz has been busy, but it’s certainly nothing new. After launching into international stardom in the global stage smash Hamilton, Muñoz proved himself to be a staunch activist by using his profile to highlight issues like HIV, stigma, #MeToo, and health care.

As a Latino gay man living with HIV who is also a cancer survivor, Muñoz has a perspective that crosses many intersections. He has worked with such organizations as Gay Men’s Health Crisis, RED, and the Latino Commission on AIDS for many years, but organizing something like the Broadway Relief Project takes a new kind of discipline — one that began with deep introspection.

“It’s been an evolution,” Muñoz says of his journey toward finding inner strength. “Everything I experienced since testing positive for HIV in 2002 — every positive-thinking construct, every part of me that finds optimism and hope — was certainly created in my journey of living with HIV. And it was triple-fold when I had my cancer battle.”

Muñoz was diagnosed with cancer in October 2015, while he was understudying Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Alexander Hamilton in Hamilton (he would later replace Miranda as the lead role). He left the show temporarily while he was going through radiation treatments, which began to take a toll on his body.

Eager to strengthen his weakened mind and body while recovering at home, Muñoz filled two bags with socks and began lifting them with his arms as weights. Over a span of many weeks, the pair of socks became five pairs, then eight, then 10. Each increment reminded him there was still life in him yet, and that was a turning point.

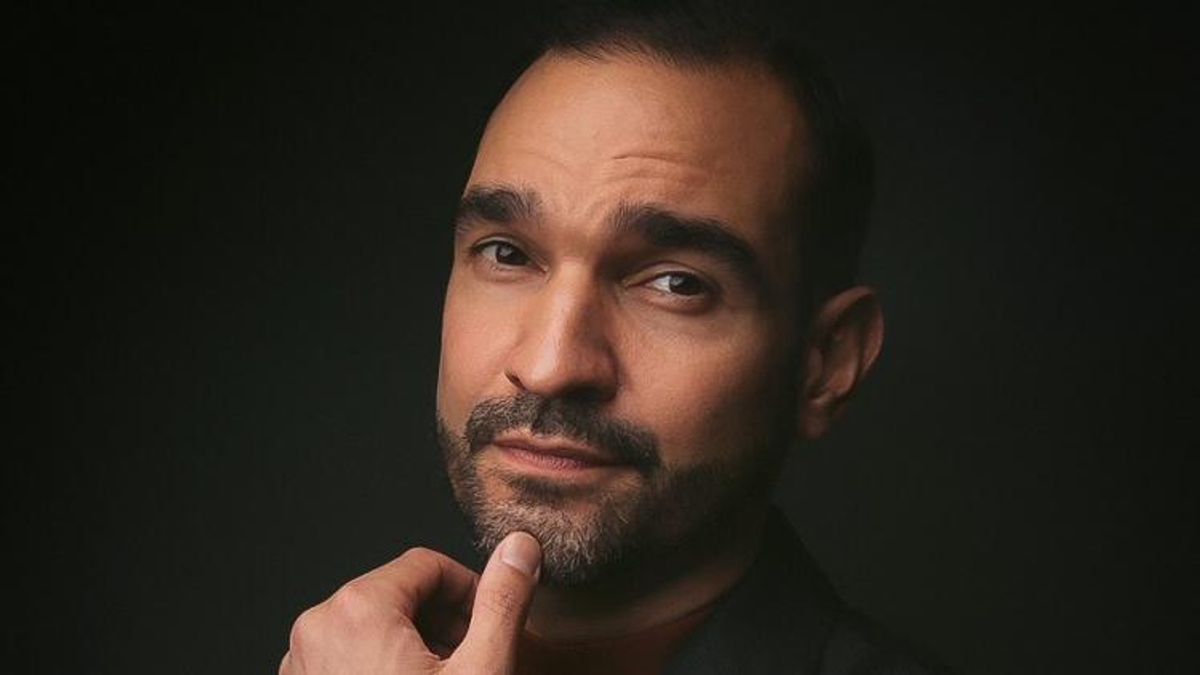

“I would stop and meditatively say, ‘Thank you, body. Thank you, Javier, for doing this today. Look at what you accomplished. You did one set of 10 reps with this exercise, with that many socks in the bag today,’” he reflects. “And the socks eventually became weights, and the weights became me working out again and getting back to physical therapy. And eventually, I went back to my show.” (Story continues below photo.)

Muñoz says his health tribulations helped him find the grace to overcome other challenges.

“I look back and I feel like I had one of two choices,” he says. “I could surrender and give up, or I can fight for my life — literally. So I fought. And in learning how to fight, [I learned how] to not give up on myself, and not give on my life, my dreams, on wanting to find love in my life and joy, because I deserve it just as much as anyone else, despite my HIV, despite my cancer battle. Those moments create an inner fire that never goes out.”

It’s not hard to imagine the optimistic Brooklyn-based performer as a talented young kid, eager to enter the world. He can’t help but smile when reminiscing about his Puerto Rican roots and how they’ve defined his identity.

“The first things I think about are food, music, and our holiday traditions,” he says. “Those are the things I think of immediately, and talking to friends about [Puerto Rican delicacies like] empanadas, gandules, pasteles, coquito — realizing people had no idea what coquito was and sharing these things with them — those are the memories I have. And music.”

Like many Latino families, Muñoz grew up with a church community. Saturdays were for sacraments and Sundays were for church dances — with a “live band and DJ, we were 6 or 7 years old and cutting it up!”

“That’s what I know I grew up with,” he says. “Those rhythms are in my blood. Those flavors are in my blood. Those traditions are in my blood.”

Muñoz is the first to admit that even in the Latino community, as a non-Spanish speaker, he can feel like an outsider.

Muñoz’s two oldest brothers were fluent in Spanish when they went to school, but as there was no ESL program in place that would teach them English, his parents “had to fight” to get them to regular classes.

“They were afraid that my third oldest brother and myself would have the same struggle, so they taught us only English [at home],” he explains. “That was also a way for my parents to practice English. My mom was trying to get a better job. My dad was trying to get better work.”

While trying to learn Spanish later in life, Muñoz says the biggest obstacle is “the judgment I impose on myself” when he hears how unnatural he sounds compared to his fluent counterparts. Still, as a Puerto Rican American, you can speak English and still be treated as a second-class citizen.

“I’ve been Latin my whole life. I’ve worn that skin,” he says. “[I was] made to feel smaller and less. When eye contact is being made with all my other friends by my white teacher but they didn’t look at me, I felt that. I absolutely felt that growing up, especially being ‘Javier Muñoz’ and just teaching people how to say my name. Those are real experiences that informed my journey, and it’s significant. Each minority in this country goes through something very specific.”

He adds, “My brown skin has been on me my whole life, and it’s been a source of my pride, really, and my fight. I am as human as anyone else and I deserve to have my dreams come true. I deserve to get an education. I deserve to get a good job. I’m going to fight for it, and I’m going to work hard for it, and I’m going to work harder than a non-minority will. But I deserve to be happy, so I’m going to put in the work.”

When Muñoz began acting in the 1990s, he found the industry consisted mainly of white spaces. However, diversity and inclusion have grown across theater and film —due in no small part to the success of the Tony-winning Hamilton. The show broke ground for casting many people of color; Broadway soon saw other big-budget hits that prominently featured actors of color, such as Hadestown and Ain’t Too Proud.

“I am so grateful to be part of a generation that helped implement that change,” he says. “When I get to turn around and look at my peers, and I mean of all ethnicities — Asian artists, Black artists, and Latin artists, across the board — and I get to walk amongst them, it’s an honor. We have come a long way, and I’ve seen every one of them fight the good fight to get us through those doors and that’s the point. We fight the fight.”

Living in these intersections, he says, has also made him a target for negativity in society. Regardless, the compassion and empathy he’s developed as result of being Latino, gay, HIV-positive, a cancer survivor, and an artist are worth the scars.

“I try my best because I’m an imperfect human,” he says. “I try to take the negativity or aggression that comes my way [and] compartmentalize as best I can and take all the good, all the hope.”

As the country continues to fight the novel coronavirus, Muñoz advises people living with HIV to utilize their stories to help drive the narrative.

“The great disservice this government, our current administration, has demonstrated is to call [COVID-19] the ‘Chinese virus.’ That is an absolute echo of when the Reagan administration called HIV the ‘gay cancer,’” he says.

“What’s empowering in that situation,” he concludes, “is as people living with HIV and as long-term survivors, we have a skill set for this. We have lived through so much that we can offer a perspective to help others. We can help other people to understand how to live through this moment — emotionally, mentally, and physically — and that’s a gift. That’s a power we have that we can offer.”