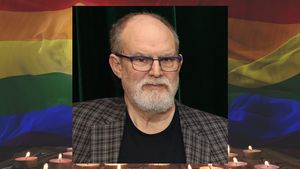

It’s never a bad time to win a Pulitzer Prize, one of the most prestigious awards given to writers and journalists. But for Jericho Brown, who was honored this year with the award for poetry for his third collection of work, The Tradition, it’s complicated.

“It’s always hard to reconcile the personal with the political, particularly if you’re a Black person who’s safe and you understand that Black people as a whole are some of the most vulnerable people living at a time like this,” Brown said from his home in Georgia, speaking to Plus this spring as COVID-19 killed tens of thousands and, as with HIV, disproportionately affected Black people. On top of that, Georgia’s Republican governor had been resistant to stay-at-home orders and was rushing to reopen the state — a choice many said put marginalized people especially at risk. The state was also reeling from the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who, while jogging, was seemingly hunted down and killed by two white men.

“Black and brown people in particular are at risk in ways that other people are essentially not,” said Brown, the director of the Creative Writing program at Atlanta’s Emory University, who is also gay and living with HIV. “So, it feels very difficult for me to have such a wonderful thing that I’ve dreamed of. I’ve been dreaming of it since I was 10 or 11 years old.”

As with his poetry, Brown is comfortable discussing both dark subject matters and those that inspire joy. Among warnings about humanity’s disregard for the environment are moving descriptions of grasses, fields, trees, rabbits, and the writer’s favorite tree, the crape myrtle.

“Another thing The Tradition is about is the natural world,” Brown said. “It’s about how we treat and understand the environment and humans’ interaction with that environment. I want people to see not just the social ills; we have one planet and it’s our job to make sure it’s still here.”

It’s hard for everyone to ignore those social ills in 2020, especially an introspective writer like Brown. Following the killings of Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade at the hands of police, demands for racial justice rang throughout the nation and world. These calls follow centuries of dehumanization of Black people.

Brown worried nothing substantially would change until there’s a dramatic shift in how the mainstream white world looks at Black lives. “We have a long way to go in understanding Black people as human beings,” he said. “The thing that allowed Tamir Rice’s death to happen was that those police officers didn’t imagine they were murdering a human being. They didn’t think for a second this kid could have liked flowers, could have had a mother.”

That systemic racism affects everything, including the health of Black people. In “The Virus,” a highlight of The Tradition, Brown writes from the vantage point of what appears to be the disease, and the virus and racism intermingle in their destructive force: “Dubbed undetectable, I can’t kill...I want you/To heed that I’m still here/Just beneath your skin and in/Each organ/The way anger dwells in a man/Who studies the history of this nation.”

“The Virus” describes the relationship between individuals and the diseases they must live with, sometimes in perpetuity.

“In spite of the fact that you know that doctors and science are telling you you’re viral load is at zero, you understand you are still at a certain kind of risk,” Brown said.

The private concerns — and sometimes paranoia — that can accompany living with HIV is now being experienced by the entire world, he added.

“People with various kinds of illnesses and health issues have dealt with this fear in an individual way and now that fear has become more communal because of this [COVID-19] pandemic.” Brown said. “So we understand what it’s like to be nervous about every little move we make. Did I just wash my hands? And all of us now are balancing the difference between paranoia and safety.”

Now in his mid-40s, Brown grew up when HIV and AIDS were deadly and stigma ran as thick as the air in his native Louisiana. But Brown doesn’t necessarily see parallels between gay and bisexual men being blamed for HIV 35 years ago, Asian people receiving blame for COVID-19 today, and people of color bearing the brunt of both diseases.

“I see [HIV and COVID-19] as a part of continuum,” Brown said. “We can look at disease and viruses and illnesses as parallel but I would actually like to broaden that. I’d like to think about other kinds of violence and mindsets as disease.”

The poet references the Islamophobia that flared after the 9/11 attacks: “People were fascinated by the fact that Muslim people live in the United States because they hadn’t seen [a Muslim person],” he said. “Yet the people who haven’t seen Muslim people are the people most afraid of people who worship differently than them. All of that sounds like insanity, which is an illness…I’m thinking of the insanity of racism. Racism is a mental disability.”

Brown doesn’t believe enough has changed for LGBTQ+ people since the AIDS crisis three decades ago.

“Gay men having HIV and dying of it in the ’80s and ’90s was only the opportunity to further show how people felt about gay people. That wasn’t new,” Brown said. “Gay people were being castigated, rounded up, beat up. That hasn’t changed. For all our talk about bullying, for all our talk about equality, supposedly feminine kids are treated horrendously and have to grow up understanding the threat of violence above their shoulders.”

Growing up, Brown was a “nerdy kid who liked to read and write.” He found solace in creative expression, something that has carried through to his adulthood, where he’s been awarded numerous fellowships and awards—including from the Guggenheim Foundation to the National Endowment for the Arts—and seen his writing appear in The New Yorker and The Paris Review.

Brown described writing as both a complicated experience, one that brings catharsis, exhaustion, accomplishment, and pain, sometimes simultaneously.

“The weird thing for me about that is while you’re experiencing the joy of having the poem, you’re also experiencing whatever the tone is producing or will produce in the reader,” Brown said. “So you might be crying while you’re in the midst of writing the poem. If you’re writing about the sad experience, if you’re writing about the joyful experience, if you’re writing about a time that you couldn’t forgive then you feel those feelings as you write the poem. And yet they are tempered by these feelings of joy that you have a poem at all.”

Even though Brown received news of his Pulitzer in the middle of a pandemic, and the awards ceremony was postponed, he is doing all he can to share the news of his achievement — and it’s not for his own vanity.

“This is the 70th anniversary of Gwendolyn Brooks being the first Black person to receive a Pulitzer, so it means the world to me to walk in her footsteps and to hold that mantle up,” Brown said. “I met Gwendolyn once. I understood her not just to be a good poet, but a great ambassador for poetry. So what’s being asked of me in this moment is to be an ambassador for poetry and I, will hopefully, be the only poet to ever receive the Pulitzer Prize in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.”

Additional photography by Brian Cornelius and John Lucas.