Boomer Banks moved to New York City for a career in the fashion industry. In Los Angeles, he had made an impression working in a flagship store of the French brand Catherine Malandrino. So when that location closed in 2011, the ambitious young man, then 31, packed up his things and moved across the country to continue his career at one of the designer’s stores in New York.

“The goal was always to move to New York,” Banks says. “Every vision board I ever had there were photos of [New York landmarks]. So the plan was to move to New York and intern part-time [in the studio] and work part-time at one of the stores.”

Getting brought into the stores happened easily, given Banks’s success on the West Coast. The compliments and recognition for his work ethic began to roll in, but the offer to intern at the studio did not. Then Malandrino sold 75 percent of the brand amid financial troubles caused by the recession. And while the company was happy to keep him on, the allure was gone for Banks.

So he did what any true New Yorker does when they’re down to the wire: He hustled and made it work. Picking up a few fashion retail gigs, sewing gowns for drag performers like Marti Gould Cummings, Chi Chi LaRue, and Sister Roma, and even doing a little go-go dancing, Banks did whatever he could to stay in the city. He hosted events and parties at Cafeteria and was one of the first dancers for Frankie Sharp’s Westgay party. This foray into nightlife brought with it photographers, hoping to shoot this new face on the scene, both in and out of clothes, which led into escorting and finally into adult films.

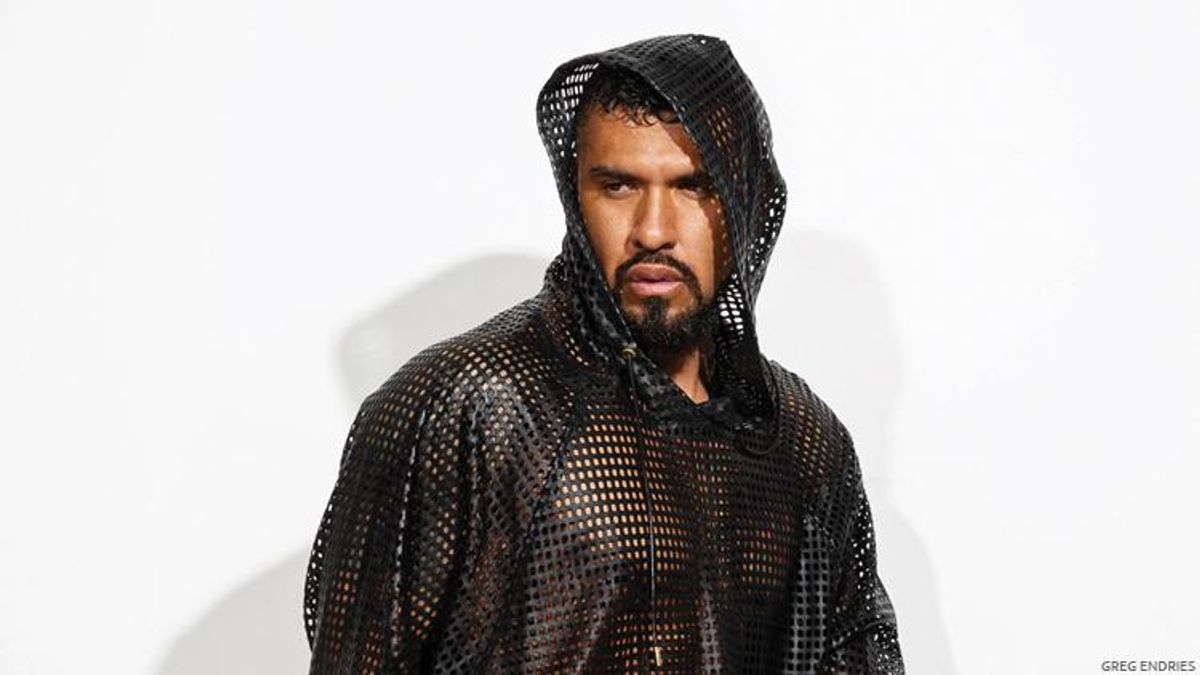

Now Banks does it all: He is a designer, adult performer, activist, and nightlife personality. He maintains his own chosen family and remains one of America’s most heavily awarded Latinx gay adult performers. He’d previously been called an angry loudmouth by contemporaries as he spoke out on injustices in and out of the adult industry — but many of those voices began to speak in similar tones this summer with the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement and related uprisings.

In many ways, Banks is just getting started.

Before he became Boomer, Banks was born in Quiroga, Michoacán, a rural Mexican town of fewer than 15,000 people.

“The biggest reference that people have of Michoacán is either the drug lords or that it’s the place that monarch butterflies go for the winter,” says Banks, who was the only child of a single mother. His father died in a car crash during the pregnancy.

Banks wasn’t in the town for long. A year after giving birth, his mom, who was a seamstress, picked up and moved the two to Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley. The move was one of many in Banks’s early life, as the pair bounced around L.A. County. This didn’t make for lasting friendships with peers, but it turned Banks into quite the independent kid.

“My only role model was my mother, this very feminine woman with long beautiful locks and fair skin,” Banks explains. His mother died at age 42 of cirrhosis of the liver, caused by alcoholism. “So I grew up very effeminate and unapologetic about it. When she passed away and I went to live with family, they didn’t know what to do with this very unapologetically queer boy. That was more important to them than the fact that I was a 14-year-old who had just lost a mother.”

This refusal to accept Banks’s femininity and queerness caused a long-standing rift between the performer and his family, some of whom refused to accept him once he moved to Santa Barbara, Calif., to live with them. Once a cousin informed the family that Banks was living as an out gay teen at school, an ultimatum was presented. Banks left home after graduating at 18.

“I thought I would be off to the horse races,” he says. “Really, it was off to the donkey races.”

After graduation, he tried a dance program at a college in Santa Maria, Calif. After dropping out, Banks moved to Los Angeles in 1999 with $187 in his pocket. When his living arrangements didn’t work out, he found himself sleeping on sidewalks. The people who cared for him were drag performers and trans women.

“They would see this little skinny Mexican walking around and be like, ‘Where are you going? Are you working the Boulevard?’” he recalls. This would turn into offers for him to sleep on their couches. “I never felt remotely sexualized. They just cared, and in the times I ever felt genuine hunger and didn’t know where my next meal was going to come from, a trans woman or a drag queen would ask, ‘Are you hungry?’”

On New Year’s Day 2001, Banks became incredibly sick. He was experiencing flu-like symptoms but didn’t want to go to the hospital. He waited, but in a few days he started to feel razor blades in his chest whenever he breathed, and he checked himself in. While doctors scrambled to find something to fight what they assumed was a bacterial infection — Banks is allergic to both penicillin and sulfa drugs — he asked for an HIV test.

It came back positive, and he had only 11 T cells left, so he received an AIDS diagnosis as well. “When my results came back, the only thing I kept saying was that I hoped my partner didn’t have it,” he recalls. The partner was also tested and received a positive result.

Banks believes his illness progressed as a result of his rampant drug use, which had begun about two years earlier. By the time he sought treatment, his lungs were struggling under an opportunistic infection, causing that feeling of razor blades. He was kept in the facility for a month.

“People talk about all these symptoms of coronavirus right now, and it really reminds me of when I was sick: no taste, no smell, the coughing,” Banks explains. And while for many, a diagnosis can be a significant turning point, when he was released from the hospital, Banks went back to using and wouldn’t get completely sober from crystal meth until 2004, when he was arrested in a raid of his dealer’s home. The arrest was the wake-up call he needed and set the performer on a new trajectory. This July marked 16 years of sobriety.

But in that almost two decades of time, Banks has changed a lot. He’s now a dad to a year-old puppy, Buster, and father to his fashion line BANKKS, which started after a 2017 collaboration with Brooklyn-based designer Bcalla. And he’s the father of his porn family, the Haus of Banks, which includes Calvin, Beaux, Brock, and Boy Banks. His busy, ongoing, and heavily awarded adult career began with Raging Stallion’s Timberwolves, shot on his birthday seven years ago. It received a sequel of sorts in Blood Moon: Timberwolves in 2019. But when the original was released, a blog ran an article outing his poz status.

“It was this really nasty story,” Banks says. The blogger had found an old Next Magazine cover Banks had done for World AIDS Day — after turning his life around, Banks had become a vocal HIV activist — and ran it alongside his legal name as well as details from his escorting account available online. “I started getting all of these messages and people who followed me all started getting these messages of like, ‘You know he has AIDS, right? You’re giving your clients AIDS.’”

“For whatever reason, this [writer] thought it was their right to tell my story,” he continues. And while that blog post is likely long forgotten by the internet, it’s clear that it still weighs on the star years later, who drops his voice when the subject comes up. These are the personal ramifications of internet trolls who ignore facts and science in favor of spreading hate into what they pretend is a void. Banks has long maintained an undetectable status and therefore cannot transmit HIV, and he informs his sex partners of his status beforehand.

Banks’s reaction to his status outing contrasts with the vocal, confident presence his followers encounter online. There, he pushes back on stigmatizing language and regularly educates followers on sexual health information like undetectable equals untransmittable, or U=U. But it’s expanded outside of that, discussing sexual racism as well as institutional racism both in the porn industry and outside of it. He has called out performers like Antonio Biaggi for their racist comments and gone so far as to criticize studios for their lack of diversity. And though in the past he had been dismissed by some of his peers, now those comments take on greater potency given the social climate.

“When people of color speak out, we’re angry,” Banks says. “People were always saying stuff like ‘Boomer, you’re too fucking loud. Calm down.’ This movement [today] isn’t about me, and I don’t want to say it is — my experience as a man of color is not the experience of a Black man — but I’ve been talking about this stuff for a long time; it’s not new for me.” Still, it’s important to the star that he not center himself in today’s conversation, but instead learn from and shine a spotlight on Black communities and the issues that impact them.

While this fall he plans to do a second push of product through BANKKS — which itself was created in collaboration with the Phluid Project, a retailer that works beyond the gender binary and puts social justice at its forefront — he also plans to recommit himself to helping those who aided him when he needed it. He has been planning a series of benefits for organizations like the Okra Project and Black Trans Femmes in the Arts, two organizations that assist Black trans folks.

“My biggest thing right now is I want to help Black trans women and Black queer and nonbinary folks,” he says. “It’s hard for me to see these nonqueer people attack any of us, so I’m going to use my platform and do whatever I can to protect our community.”