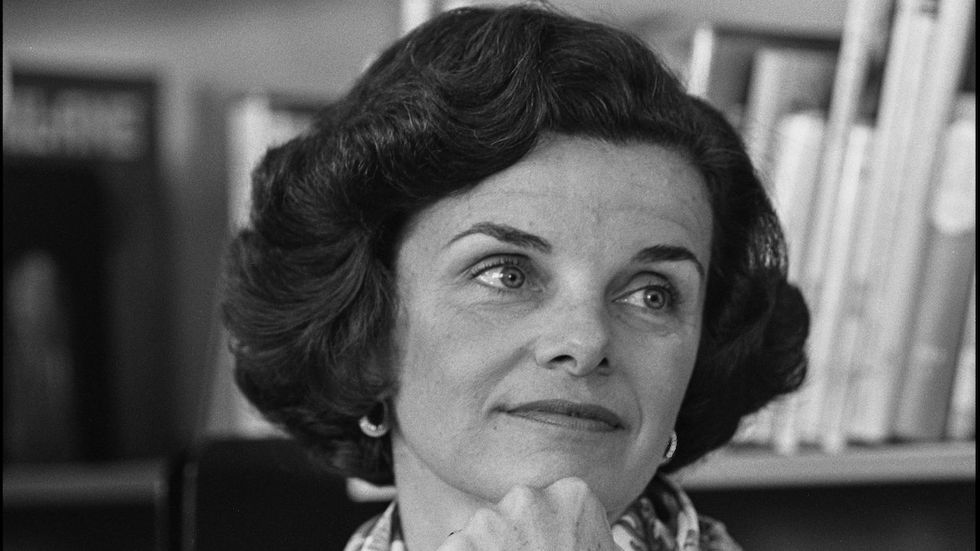

The first thing I remember about late Senator Dianne Feinstein was her height. After I had moved to New York from Capitol Hill in the mid 1990s, I was invited to a private fundraiser for her in Manhattan by one of my high-powered lobbyist friends. When Feinstein entered the apartment, which had a high ceiling, I remember how she seemed to tower over everyone.

The juxtaposition of that image to that of her returning to the Senate in a wheelchair earlier this year after recovering from a bout with shingles was jarring. It was also incredibly sad. I texted my lobbyist friend, since retired, and reminded him about that first time I saw her. “Yes,” he replied. “She was bigger than life.”

When I wrote about Queen Elizabeth upon her death, I talked about marveling at how small she was the first time I saw her in person, but how she towered above everyone else. In Feinstein’s case, she was bigger than life in so many ways.

I did not know much about her back in the 1990s. She came to the Hill the year that I left; therefore, I wasn’t aware of her as mayor of San Francisco, and how that role was thrust upon her when her predecessor, George Moscone, was assassinated along with the history-making gay trailblazer, city supervisor Harvey Milk. As the president of the Board of Supervisors, she was next in line for mayor.

But after meeting her, and hearing about her career up to that point, I found a book about her at the Strand Bookstore in downtown Manhattan, Never Let Them See You Cry, which was primarily about her time as San Francisco mayor during the AIDS crisis.

From my friends on the Hill who knew her, and one friend who worked for her, she was described as no-nonsense. “She was definitely not the easiest person to work for, I’ll say that about her,” my friend told me once.

My friend had worked for Senator Alan Cranston, who was succeeded by Barbara Boxer, prior to joining Feinstein’s staff. “Alan, and everybody called him Alan, was pretty cerebral, and a bit eccentric. He’d wear the same suit multiple times during the week, but he was easy to work for. Then I went to Feinstein, briefly, and the only thing she had in common with Alan was their height.”

She said that after about six months of working overtime constantly, she left the Hill, and went to work for a lobbying firm. “I always respected her so much, so don’t get me wrong. But I just couldn’t work for her. Looking back, I understand that she had to fight twice as hard as the men, so she could be forgiven for her intensity. I appreciate her so much more than I did while I worked for her. She’s one of my idols.”

After I read Never Let Them See You Cry, she became one of my idols too. So much has been forgotten about those early days of the AIDS crisis because new generations have come and gone, and as I wrote recently (see page 42), the survivors from those days, and the caregivers of the early AIDS victims, are starting to die.

Through her leadership as mayor of San Francisco from 1978-1988, Feinstein, in her own way, was a survivor of those early days of the epidemic. I remember reading in the book about her father being a doctor, and that that gave her somewhat of an understanding about making sure AIDS patients were cared for, both personally and professionally. The city of San Francisco, with way less than 1 million people, was spending more money on AIDS treatment and care than the entire federal government was in the mid-1980s.

I reached out to Feinstein’s friend of over 40 years, longtime political activist and gay icon David Mixner, who confirmed that Feinstein took great care of the community during two difficult eras, the Milk assassination, and the early and awful days of AIDS.

“She always rose to the occasion,” Mixner recalled. “She always had time to make calls to those who lost their partners or their close friends. I received several calls from her after close friends had died. She would say that we all need to treat each other especially well through these difficult times. You have no idea what those calls meant to me. She grieved with us, not for us.”

According to Mixner, Feinstein, along with California congressmen Henry Waxman and Phil Burton, were the pioneers in lobbying for AIDS legislation and funding. “Whenever we had a problem with DHS (Department of Health and Human Services), NIH (National Institutes of Health) or anyone else, we called her, and if I called her in the morning, she would always call back by the afternoon. She never ignored us.”

Mixner’s association with Feinstein went back to her first run for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in 1969. “I got a call from a dear friend of mine in San Francisco while I was living In L.A., and he asked if I could have a fundraiser for her, and of course I said yes. I got a group of professional gay men together, and we all got behind her. She was a young woman back then in a world that was dominated by all white males. We supported her because she was good on issues that affected our community. She was a rarity back then.”

Mixner said that after the assassination of Moscone and Milk, it was Feinstein’s strength and leadership that led the way. “Her character not only helped our community get through that horrible time, but also helped the city and the nation as well. After that, she was literally at the forefront of our fights with “don’t ask, don’t tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act. And to the latter, she supported marriage [equality] at a time when only 10 percent supported marriage. She had her own struggles with the issue, but she always came out one step ahead of everyone else.”

I told Mixner about my friend, who revered Feinstein, but talked about how hard it was to work for her. “She demanded excellence, and she expected everyone around her to put in the time and effort that she did. Yes, people got burned out, but Senator Feinstein never did.”

And Feinstein didn’t suffer fools. “I recall being in her office for a meeting, and a lobbyist kept talking and talking. She stopped him, and said something to the effect that if you have something relevant to say, please say it now.”

To Mixner, Feinstein represented an era when senators were old-school and had reverence for the institution. “In the Senate’s history, she will be remembered up there with giants like Senator Ted Kennedy.”

“But personally, she will be remembered for her compassion and generosity. She lived life the way she saw the world, and she was so generous with her time and her wisdom.”

---

John Caseyis a contributing editor for Plus. Views expressed in Plus’s opinion articles are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent the views of Plus or our parent company, equalpride.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web