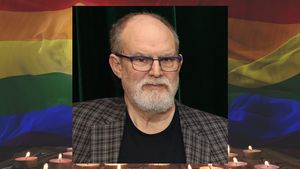

Getting older isn’t easy, but the addition of HIV to the aging process is uncharted territory, both medically and psychologically. Perry N. Halkitis, a New York University professor of applied psychology and public health, explores the topic in his new book, The AIDS Generation: Stories of Survival and Resilience. The book contains interviews Halkitis (pictured, left) recently conducted with 15 gay men who contracted HIV before 1996, a time when most people died within a few years of their diagnosis. Each man tells his story of survival during the 1980s and early ’90s and what his life following that harrowing period has been like. Perry talks to us about aging in a youth-obsessed culture, the missing mental health link, and why “survivors’ guilt” is overstated but mental health counseling is crucial for people with HIV.

Why is the subject of aging HIV-positive people so important?

First of all, you have this aging of America, and in this aging there are a lot of LGBT folk. We know very, very little about Baby Boomers in general and very little about those who are LGBT and almost nothing about those who are LGBT and HIV-positive.

Gay culture is known to emphasize youth. How does that affect older HIV-positive gay and bi men?

I’m a 50-year-old gay man myself, so I feel [the youth obsession]. I’m not going to just point the finger at the gay community, because I think [society in general] is youth-obsessed. However, it seems more pronounced in the gay community. So for those men, many of whom have felt rejected and invisible anyway because of their HIV status, there is this double invisibility.

Does HIV stigma affect longtime survivors and the recently diagnosed the same way?

The stigma is still there. This notion that it somehow disappeared over the course of the last 32 years is ridiculous. Here’s what I really think has changed: We know how this virus operates and we have effective treatments that, if properly administered, can handle it. It’s like we’ve moved forward in so many ways with this epidemic, but it’s like we’re reacting to it emotionally like we did in the ’80s.

We hear a lot of stories about men who become positive while using recreational drugs. What’s the most important link between HIV and drug use?

It’s not just HIV and drug use, I think it’s HIV, drug use, and mental health. I say this all the time to my students: “Show me a drug problem and I’ll show you a mental health problem and I’ll show you sex risk.” They fuel each other.

Tell us your feelings on HIV survivors’ guilt.

Tell us your feelings on HIV survivors’ guilt.

I don’t believe in this notion of survivors’ guilt. I think it is an overstated psychopathology. There is limited research to support that it actually exists. Absolutely, the men in my generation, including myself, have feelings of sorrow. When I was writing the book I thought I had very easily put all of these emotions away, but as I was writing they all came forward. But I don’t feel guilty that I’m alive. I feel happy that I’m alive.

You don’t like the label “men who have sex with men.” Why?

Gay is a sexual orientation, and being gay is associated with a certain community and a way of understanding oneself. MSM is a term the Centers for Disease Control developed in the early ’90s as a way of categorizing people who got HIV transmitted to them through sex with another man. They did that because there were a handful of these men who did not identify as gay. They were closeted; they were married. But the vast proportions of men who have sex with men are gay, and to deny their sexual orientation and to deny our sexual orientation is disrespectful. I want to be labeled as a person whose sexual orientation and sexual identity is that of a gay man. And the way you would provide services for a gay man is very different from the way you provide services for a man who is married to a woman and who has sex with men.

Were there certain men you interviewed whose stories really resonated with you?

Kerry, who I’ve gotten to know a lot better since the book, his life became derailed because of this epidemic. His career became undermined and he struggles so much and speaks so eloquently about his ability to not really remember and think clearly. He sticks out really, really clearly in my mind. And then there’s Richard, the musician, who talks about how he finally went up to the piano and how he felt the energy coming back into his body after he was almost dead.

During the interview process, what was the most surprising thing that you discovered?

How every single one of those men, regardless of when they found out about their status, were convinced they’d be dead in two years. Eventually all of these 15 guys were able to not only tend to their physical health but to their emotional and social well-being. And the role of mental health counseling was so crucial.

Tell us your feelings on HIV survivors’ guilt.

Tell us your feelings on HIV survivors’ guilt.