The series of sexy, slick videos of Time2PrEP’s educational campaign may be raising eyebrows by tapping a porn star as a role model, but the effort is informed by behavioral science. Not to mention Kenny Shults’ childhood in New Orleans and years of real world efforts doing what Shults calls “getting into people’s heads.”

Shults has always wanted to change the world. A young man who handed out condoms in gay bars, he grew up to become CEO of Connected Health Solutions, a public health media company that creates social marketing campaigns and public service announcements (PSAs) to help at-risk teens, the LGBTQ community, people living with HIV, and other disadvantaged groups.

His latest effort is a collaboration with Gilead Sciences and Public Health Solutions’ “HIV is Still a Big Deal” program. (Check out an interview with an epidemiologist about the campaign, working with J.D. Phoenix and how PrEP is a “gateway drug” here.)

Despite criitic fears that the campaign and PrEP in general could lead to more risky behaviors, Shults is confident his approach will reach gay men and empower them to make healthier sexual choices.

Shults was 22 when he took a job as a community educator at Texas' AIDS Services of Austin.

“At that time HIV/AIDS was the overriding issue impacting our social advancement and acceptance, and there was still so much grave injustice surrounding the epidemic," he says.

In those pre-antiretroviral therapy days, Shults remembers people “dying in droves. I watched the case managers at ASA wither and grow bleary eyed by the sheer number of clients they lost each month.”

It was his job to do preventative HIV education, but Shults said there were mixed feelings about his role at ASA. “There was such a great need to provide support and services to people who had already contracted HIV,” he says. “Ironically, the effort to prevent future infections was unconsciously resented by much of the staff and I think they saw me and my work in the bars as frivolity.”

Shults preserved and launched one of Atlanta’s first support group for HIV- negative men, then conducted a series of retreats and presented workshops.

Activists around the country were beginning to distribute condoms to prevent HIV from devastating the gay community, but Shults says he learned how “jarring” it could be for some of people in the trenches to “hear such a deliberate focus on HIV negative men.” In fact, he says he was stunned at how “volatile” things got.

“I got a few death threats,” he remembers. “The assertion that we should examine how the epidemic might be impacting negative men and structuring efforts to gain insight into how prevention efforts could be tailored to meet their particular needs was seen as an affront to people living with AIDS.”

Shults believes, “This is why the difference between primary and secondary prevention was ignored," and he says, why prevention messages never got past broadly focused attempts to address everyone with the same campaigns. It was really that experience that propelled Shults down a career path helping organizations develop public education messaging that is “ethical, population informed, and highly tailored for a precise target audience.”

Although there can be enormous differences between various demographics, Shults believes that younger gay men have more in common with older gays then people might think.

“I just don’t think you can grow up in a time of AIDS and not be [dramatically impacted], regardless of when you were born into it,” he says. “I hear a lot of folks making comparisons between older and younger gay men, and they say a lot of the things adults love to say about young people in general: ‘they think they’re invulnerable, they have no respect for what their elders endured, they’re entitled.’”

Shults argues that those generalizations are “as dangerous as they are superficial… people cope with unimaginable tribulations in ways that seem strange to us, so we judge them, and make assumptions about the perspectives and feelings that motivate their behavior.”

But, Shults says, when researchers spend the time to really uncover why young gay men still put themselves at risk, “we see many of their behaviors are motivated by fear, shame, and counter-intuitive, unconscious beliefs. The internalization of the trauma associated with the epidemic did not cease at the introduction of ARTs, or PrEP.”

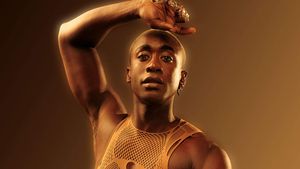

Still Shults admits, he’s disturbed by the rates of new infections among young gay men, and says “it’s even more alarming that black youth account for a hugely disproportionate number of new infections.”

He says it’s critical to understand the “social determinants” that impact increased HIV risk (and negative health outcomes) among gay men of color. “Homelessness, substance use, inadequate education, feelings of isolation — these are all larger social problems that dramatically impact and influence incidence. We need programming and approaches that deal more holistically with the factors that influence HIV infection.”

And, he thinks better marketing is critical in the effort to end AIDS. “We’ve relied too long on prevention efforts that shame, judge, and instill fear.”

Shults says that these approaches rarely work, but they have characterized the majority of prevention messaging, regardless of whether it originated inside or outside of the queer community.

Over the years, Shults has helped numerous organizations and individuals develop messaging that engages and inspires. One way he likes to shake up people’s though processes is to ask what Shults says is a “trick question.”

He asks, “Who’s more afraid of the river flooding? The people who live right on the river, or the people who live uphill?”

“You would think the people who stand to lose their homes would be more afraid, but in fact, they don’t have that luxury,” Shults argues. “When I was a kid growing up in [New Orleans] the weather guys during hurricane season would often tell us to ‘leave town and stay in a hotel.’ We literally laughed. Not only could we not afford to leave town or even afford a single night in a hotel, but because we knew we had no other options we put tape on our windows and made fun of the alarmists.”

People at risk cope with fear, Shults says, by “downplaying the realities that surround them. It’s a very valuable tool, otherwise we would live our lives in terror every moment. Hell, getting into a car would be petrifying if we didn’t believe on some level that we won’t be one of the statistics.”

It’s this same “sophisticated denial mechanisms we are all so adept at maintaining,” that Shults thinks leads people to take unnecessary risks around HIV.

Originally “ambivalent” about PrEP, Shults says he could see the treatment as a “giant pharmaceutical company bent on getting all gay men on their chemicals [or] a method for men who won’t use condoms to remain negative and keep from spreading the virus,” but he also worried, “Is this going to decimate all our work promoting and branding condoms?”

But then Shults thought back on work he did with a needle exchange program the 1990s.

“It was a powerful experience for me,” Shults recalls. “It shaped my understanding of the potential for harm reduction. The people I met and gave needles to were drug users, and rather than trying to tell them that they shouldn’t use drugs, we helped them stay HIV negative until they figured that other stuff out. The people we helped stood a much greater chance of surviving the AIDS epidemic and their substance dependency than those not served by the exchange.”

That’s why Shults says it’s now “very clear to me that PrEP is right for some people…There are some men who are not using condoms. It doesn’t matter if we think they should, they’re just not. It’s not our place to ice them out and abandon them. It’s our job to keep them negative until they can figure that other stuff out.”

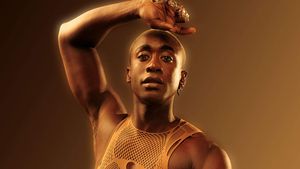

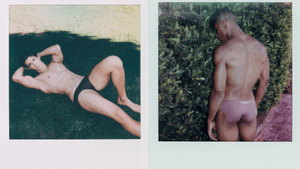

He’s not only thrown his support behind PrEP in the latest educational campaign but he made the controversial choice to devote one of the three videos to adult film star J.D. Phoenix and his, “I like to party, I like to be safe,” message.

Asked if he didn’t think that was an inflammatory choice, Shults is adamant: “Yes, I absolutely do. That’s the plan. There’s a lot of noise online, and when you’re relying on an organic social media distribution of web content you have to get people’s attention.”

In fact, he says, “We also wanted to find the ideal incarnation of Weinstein’s ‘Truvada Whore.’ J.D. is perfect! I say this with all respect, J.D. has been on PrEP long before it was well-known and makes no apologies for his work in porn or love of sex.”

That’s exactly the kind of spokesperson that can reach the younger demographic that Pheonix represents. It’s important, Shults says, that the message isn’t judging their lifestyles or choices. “Yes, using drugs and having unprotected sex is risky – everyone is clear on that. But it is our job to bring those men into the fold and meet them where they are, not kick them off the island and suggest that they get what they deserve.”

Shults reiterates, “No one deserves to get a disease because of the way they experience intimacy. Our job is to supply people with the facts and let them make their own choices. They are much more likely to trust what we tell them when we don’t presuppose they will make what we consider to be the wrong ones.”

Read more about the campaign as well as interviews with Kenny Shults, Mary Ann Chiasson, and Michael Lucas.