Here’s my favorite childhood memory. I was about 10 years old. My mother and I were in New York City to see The Lion King on Broadway. I’m sure the show was fantastic, but I remember my mother more than the play. She transformed on the streets of New York before my eyes.

It’s remarkable when you realize your parents have separate lives, separate identities. They are not a unit of one. My father was a dogmatic presence. He judged the world by a rigorous ethic: Excess is a sign of liberal, secular decadence. He practiced an uncompromising religiosity, refused to eat at “white tablecloth restaurants,” fixed his own farm equipment, and distrusted people with expensive cars and stylish clothes. He was hot-tempered and rough.

My mother, I always believed, was his sidekick, the softness to balance his hardness, the adjacent bolster to his furor. But over two days in New York City, she became something else. She wore a coat I have never seen her wear before or since. It was wool, calf-length, with a Native American pattern on it, dashes of crimson, brown, and olive running down the back.

I followed her through the glass city. She knew where to go. We walked up escalators and down stone steps, through clothing stores and halls of perfume. Gone was the woman I knew before. She was regal and confident. We went to the Statue of Liberty and took pictures of ourselves at the tip of the ferry, waving back at home with the statue behind us. My mother hailed taxis like she had done it a hundred times. She was a bohemian businesswoman enjoying Central Park with her son. I followed behind her in awe.

For two days, the city was freezing, but it refused to snow. On our last night, as we walked out of the play, a light snowfall started in Times Square. The city went silent. There was no one around. We tiptoed through the snow, past the illuminated billboards, unable to speak. In that moment, it was me and my mother and no one else in the world.

Two days ago, my mother donated $100 to my fundraising efforts for AIDS Walk New York. This will be my first AIDS Walk. I moved to Manhattan one month ago and wanted to show my love to the greatest city in the world. My parents moved me here. On the trip, I watched my father — softened in my years away from home. Where had that gray hair come from?

And my mother, huddled against the cold of the street, near tears as I wave goodbye. I remember when I told her I had HIV. I called her from Los Angeles to tell her I was going public with a secret I had kept from her and everyone else in my family for three years. “I’m fine,” I assured her. “I’m on meds and taking care of myself. I just wanted you to know.”

She called me later that day to tell me she was sorry — sorry that she hadn’t been supportive when she needed to be, sorry I had felt unable to tell her when I first tested positive. I needed to hear it. I was standing in the parking lot of a movie theater hearing my mother tell me that she wished she had been there to help me get through those first years. I wish she had too. “It’s OK, Mom,” I told her. “I made it. It’s OK.”

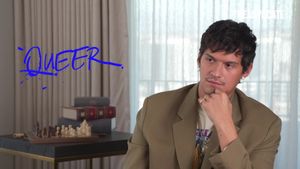

The AIDS Walk is for many people. It's for the queer men and women who’ve fallen to this unimaginable and relentless disease, for the many more who will die before we find a cure, and for the trans, brown, black, undocumented, Latinx, genderqueer, and nonbinary people still under attack, still underserved and unreached in their battle against HIV and AIDS.

It’s for the many mothers whose sons never told them, “I’m going to be fine.” How many more do we need to lose? In a different decade, my mother would have lost me. I live, and I run for her.

Please consider donating to my fundraising page: NY.AIDSWalk.net/alexlovesnewyork.

ALEXANDER CHEVES is a New York-based writer. Follow him on Twitter @BadAlexCheves.