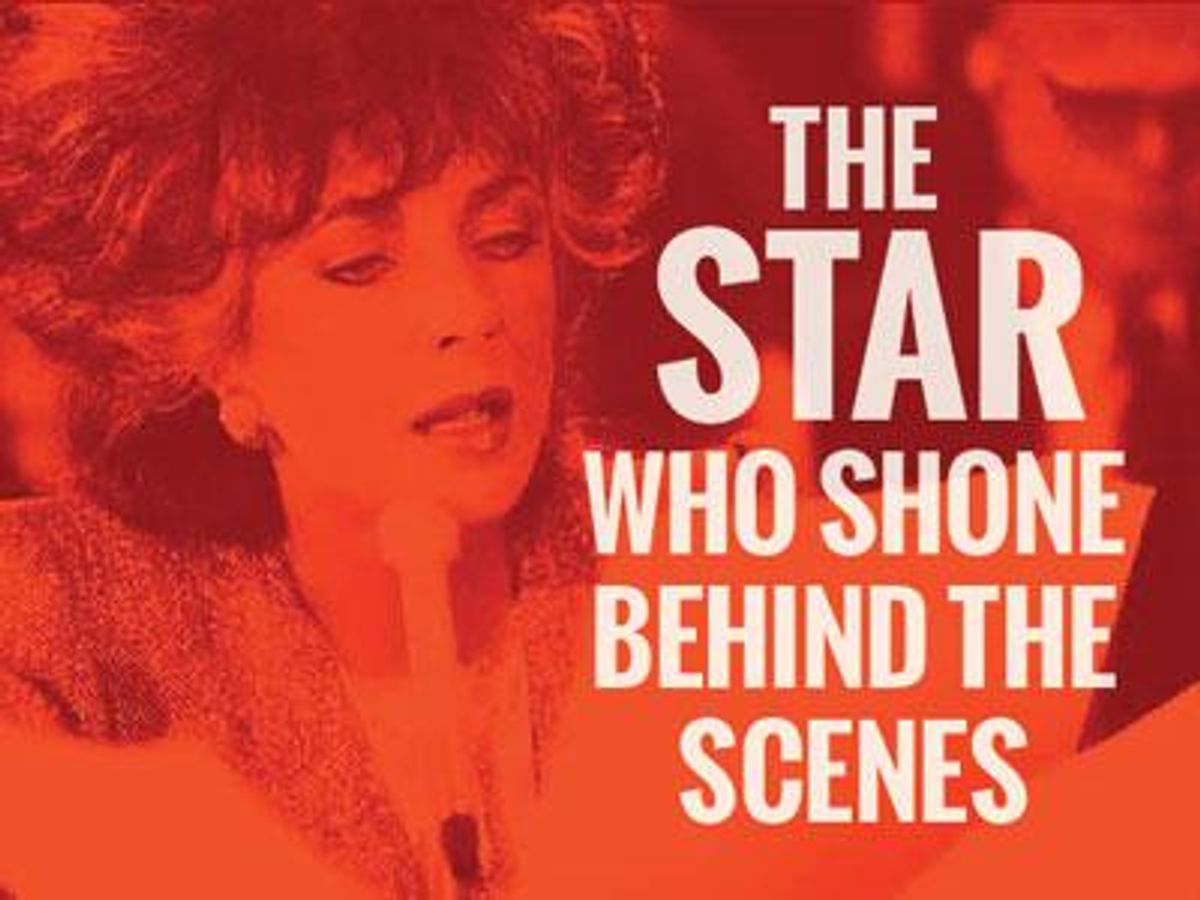

Elizabeth Taylor had a stellar film career, but a new documentary makes clear that her greatest role was that of AIDS activist, and her greatest costar was research scientist Mathilde Krim.

The two women came together from different worlds to create the American Foundation for AIDS Research (now known as amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research), in 1985, early on in the pandemic. Their work and the breakthroughs it enabled form the subject of the HBO doc, The Battle of amfAR. It’s the latest film from Oscar-winning director-producers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman (Lovelace, The Celluloid Closet, Common Threads: Stories From the Quilt).

Fashion magnate Kenneth Cole, who chairs amfAR’s board of trustees, brought the idea to the filmmakers. “He called us out of the blue and pitched us this story, and we jumped at the chance,” says Epstein. They were gratified to not only tell the story of these extraordinary women but to also remind audiences that despite advances in treatment, AIDS has not gone away, and there is still much work to be done around the disease.

“I think there is a sense of complacency, not just about supporting the research but about being safe,” Friedman says.

When amfAR was founded, there was no complacency on the part of gay men and injection-drug users, as both groups were being ravaged by AIDS, but the rest of the world considered the disease someone else’s problem, and some even figured people with AIDS deserved it. Taylor and Krim helped to change those attitudes.

The Battle of amfAR depicts Taylor’s devastation at learning her friend and costar Rock Hudson had been diagnosed with AIDS. It also reminds viewers that the epidemic hit close to home for Taylor in another instance: Her former daughter-in-law, Aileen Getty, has been living with the disease since 1985.

Krim, a distinguished scientist with Hollywood connections—her husband, Arthur Krim, was the longtime chairman of United Artists and founder of Orion Pictures—approached Taylor about working together to fight AIDS. The women created a foundation that could make research grants more quickly than any government entity. Among amfAR’s many accomplishments, it has funded studies that were key to the development of protease inhibitors, which have made HIV manageable for many patients; helped convince Congress to pass the Ryan White CARE Act, a primary source of federal money for community-based AIDS service providers; and financed research that may lead to a

cure.

In the service of their cause, Taylor and Krim used their intellect and charisma to reach diverse groups of people. The film shows how Taylor dazzled members of Congress with her star power and even persuaded old Hollywood colleague Ronald Reagan to break the silence on AIDS that characterized his presidency. Yet she was equally at ease counseling injection-drug users.

“I think we were both surprised by how involved Elizabeth Taylor really was,” Friedman says. Adds Epstein: “We of course knew she was passionate, but we never really saw her in action.” Taylor, who died in 2011, is remembered for her activism almost as much as for her film career, but The Battle of amfAR stands to raise awareness of her AIDS-related work even more.

Mathilde Krim, though, is equally the star of the documentary. The film details what led her to a scientific career: As a young woman, having grown up in Switzerland in a largely apolitical family, she was shocked to learn of Nazi Germany’s atrocities, and her parents dismissed the reports as “propaganda.” So she decided “to replace all of this stupidity with facts, with real knowledge,” she says in the film. She earned a Ph.D. from the University of Geneva in 1953, making her one of the few women of the era with an advanced degree in the sciences. She pursued her research career in Israel and, after her marriage to Arthur Krim, in New York City, where she worked in cancer research before becoming amfAR’s founding chair.

Epstein and Friedman describe Krim, now in her 80s, as a “force of nature,” and their movie indicates she’s not only an accomplished scientist and advocate but also a woman comfortable in many environments. Jeffrey Laurence, amfAR’s chief science adviser, tells a story of her being charmed by a Mr. Leather at a gay pride parade, and footage of a dinner party shows her entertaining amfAR colleagues along with longtime showbiz friend Woody Allen, who speaks knowledgeably and eloquently about AIDS.

Another attendee at the party was Regan Hofmann, a journalist, global health consultant, and amfAR board member who was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1996. She “can’t say enough” about the work amfAR has done or the people behind it, she says. “I owe my life to amfAR, literally,” she explains, referring to the drugs, made possible by the foundation’s research, that have kept her alive.

She points out, both in the film and talking with HIV Plus, that she’s one of the lucky ones—she has insurance and access to treatment. But constantly taking pills is no picnic. “You get tired of taking them, and they have side effects,” she says.

So, she says, while there remains a need to assure that all those who require treatment can obtain it, and remind people, as the film does, that AIDS is still a huge global problem, it’s also important to work toward a cure—something that looks more and more like a possibility, even a probability. Hofmann and the filmmakers say they hope the documentary will get viewers thinking about this, as it notes advances toward a cure such as the case of “Berlin patient” Timothy Ray Brown, who has stayed HIV-free after a bone marrow transplant, even after going off antiretroviral drugs.

“There is a legitimate hope for a functional cure in the lifetime of people living with HIV today,” Hofmann says. “This is an exciting time. I hope people who see this film will be inspired to finish the job.”

The Battle of amfAR premieres December 2 at 9 p.m. Eastern/Pacific on HBO.