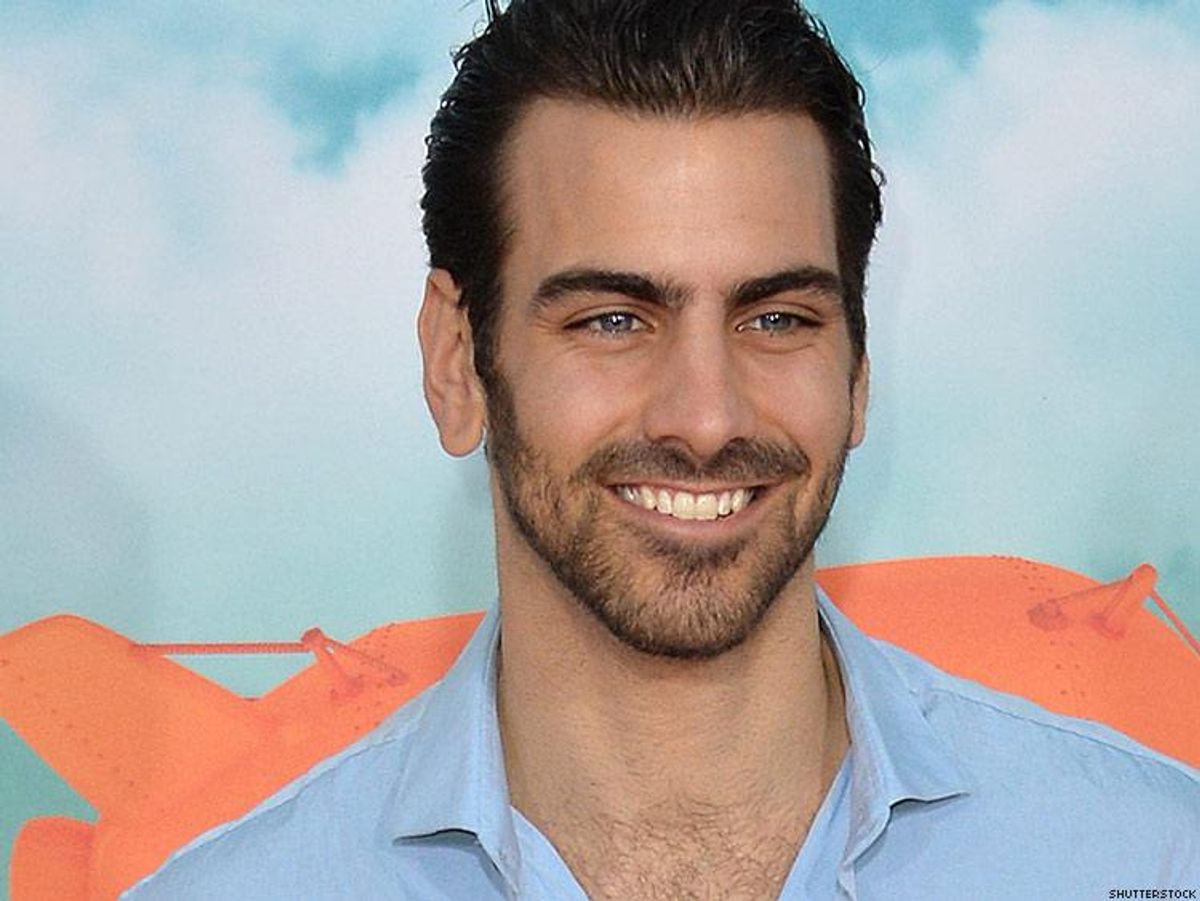

Much of America shed tears of joy last May when hunky, sexually fluid America’s Next Top Model winner Nyle DiMarco—who is deaf—won Dancing with The Stars. How could he dance if he couldn’t hear the music? DiMarco’s personality, tenacity, hard work and determination to overcome seemingly impossible obstacles provided an inspiring symbol of success only a few would have even dared imagine.

But the DWTS contestant went one step further—performing the first-ever, riveting same-sex dance on the popular ABC show, illuminating an intersection between the LGBT and disability communities that is longer and deeper than many realize. Indeed, developing not only a bridge between the two siloed rights movements but a bond based on commonalities could lead to the lessening of societal stigma, greater efforts at suicide prevention and an expansion of workplace possibilities for both during these difficult political times.

The intersection and connection between the LGBT and disability rights movements was a key point addressed at a Netroots Nation panel on July 13. LGBT legal icon Chai Feldblum, the first openly lesbian commissioner of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), moderated the panel with Rebecca Cokley, executive director of the National Council on Disability, Shannon Price Minter, transgender legal director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR), and Anupa Iyer, attorney and advocate for people with psychiatric disabilities.

Aside from a vague awareness of the sizable number of LGBT deaf students at Gallaudet University, perhaps most LGBT Americans think of LGBT-related disabilities in terms of the historic and controversial inclusion of HIV-positive people in the 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA)—a comprehensive civil rights law created to protect discrimination in employment and public accommodations based on physical or mental disabilities.

Feldblum served as lead attorney for the team drafting the ADA when she was legislative counsel to the AIDS Project of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1988 to 1990; she had been diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder in 1985 at age 26 after graduating from Harvard Law School. She went on to clerk for First Circuit Appeals Court Judge Frank Coffin and Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun. She later took the lead drafting the original Employment Non-Discrimination Act and the ADA Amendments Act of 2008.

In 1987, the Supreme Court ruled that a person with a contagious disease is protected under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 as a “handicapped individual” and cannot be “denied jobs or other benefits because of the prejudiced attitudes or the ignorance of others.” The decision was used by HIV/AIDS legal advocates arguing for inclusion in the ADA “to shield people from arbitrary exclusion based on fears of infection, including in those cases in which the plaintiff’s HIV is largely asymptomatic.”

“I didn’t realize I was living through cultural change at the time,” Feldblum said of the intersection of the disability and LGBT movements in the 1980s. “It was quite consequential.”

“AIDS changed everything,” said Minter. “It laid the foundation for visibility and overcoming generations of shame.”

And it was during the AIDS crisis—when there were no medications to staunch the horrendous daily dying—that the “power of allies” came to the fore, said Minter. The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and Citizens with Disabilities stuck with HIV/AIDS activists during the fight for the ADA.

“Even at the eleventh hour, after two years of endless work and a Senate and House vote in favor of the act, the disability community held fast with the AIDS community to eliminate an amendment which would have excluded food-handlers with AIDS, running the risk of indefinitely postponing the passage or even losing the bill,” according to the 2009 book Disability: The Social, Political, and Ethical Debate. Passage of the ADA meant that accommodating a person with disabilities was “no longer a matter of charity but instead a basic issue of civil rights.”

Nonetheless, rabidly anti-LGBT Republican conservative Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina succeeded in keeping in a provision that said that “disability” would not include “transvestism, transsexualism, pedophilia, exhibitionism, voyeurism, gender identity disorders not resulting from physical impairments, or other sexual behavior disorders.”

As of 2012, people who are transgender or gender-non-conforming no longer have their identities classified as a mental disorder.

Additionally, the White House, the Department of Justice and the EEOC have declared that transgender people are protected under the Equal Protection Act of the U.S. Constitution, thereby essentially rendering that ADA exclusion moot.

But there is still some question about whether treatment for the anxiety sometimes created by the process of coming out and transitioning, as well as the traumatic stress of having been or always expecting to be bashed or killed—anxiety and trauma that could lead to problems on the job—is available to transgender people through the ADA.

This is no small matter. According to the 2009 National Transgender Discrimination Survey, “transgender people are four times as likely to have a household income under $10,000 and twice as likely to be unemployed as the typical person in the U.S. Ninety percent of those surveyed reported experiencing harassment, mistreatment, or discrimination on the job. Almost one in five reported being homeless at some point in their lives.”

Poverty, joblessness, homelessness, constant discrimination and harassment—as well as persistent food insecurity—produces a type of anxiety known as gender dysphoria (GD) and culturally-induced post-traumatic stress disorder. Could such PTSD be covered by the ADA?

“I was diagnosed with PTSD over a quarter century ago, having been raped and tortured as an adolescent. I never directly related that to being trans, nor did my physicians. It was actually related to my reproductive intersex status,” longtime transgender advocate Dana Beyer, Board Chair of Freedom to Work and Gender Rights Maryland, said in an email. “Regardless, it all comes down to coding. I don’t know of anyone who’s tested GD as a disability, but there is certainly medical reimbursement for it. I also think a critical issue is that PTSD in these cases is not derived from trans status itself, but the abuse that comes from being perceived as trans. I don’t think that’s covered by the ADA exclusion.”

PTSD, per se, however, “is diagnosable, and the cause is irrelevant. I don’t foresee a problem with it,” Beyer said. “PTSD manifests in a myriad of ways. The manifestations can range from mild to severe. If you were to develop severe symptoms and crash emotionally, you would get treated like any other PTSD patient. And if you were fired as a result, it would be because of a recognized mental illness and that’s illegal. Of course, if you were fired for being trans, that’s discrimination under Title VII [handled by the EEOC]. The PTSD is not relevant.”

To be sure, the ADA has made many visible improvements. But there has been less attention—especially in the LGBT community—to protected non-visible disabilities such as epilepsy, depression, alcoholism, anxiety disorder, dyslexia, attention deficit disorder and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Nearly 50 million American adults aged 18 years and older are affected by disabilities; more than 10 million live with physical or mental disabilities that necessitate ongoing assistance with day-to-day or other instrumental activities. A 2012 study by the American Public Health Association found that “the prevalence of disability is higher among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults compared with their heterosexual counterparts; lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults with disabilities are significantly younger than heterosexual adults with disabilities.” The study concluded the higher rates warranted “major concern.”

The Center for American Progress noted that intersectionality, reporting last year that “nearly one in five adults has a disability or will experience a disability at some point in their life. It’s estimated that between 3 and 5 million Americans with disabilities also identify as LGBT. [CAP] also found that 14 percent of [low- and middle-income] LGBT people had received Social Security Disability Insurance at some point in the past year.”

The Netroots Nation panel also pointed out similarities such as being labeled as “the other” or “different” from “the norm;” societal discomfort leading to institutionalization for physical or mental conditions, with LGBT victims in the 1950s suffering lobotomies and chemical attempts to “cure” or “change” the “perverted” LGBT person.

Another similarity is the constant fear of violence, of being bullied, beaten up, or even murdered on a whim, as if the LGBT or disabled person is somehow less that human and worthy of degradation or violence. This results in constant vigilance and constant negotiation in public spaces, including how to maneuver in school, the workplace, housing, and public accommodations such as hotels or bathrooms. Often the language of the legal and medical systems is inadequate, insensitive and culturally incompetent, especially for people with hidden disabilities such as people living with HIV. And too often the societal response is that the disabled person is seeking “special treatment” or “special rights.”

Such constant pressure can unsurprisingly lead to suicide.

The panel urged people to fight back by coming out.

“The importance of coming out about a hidden disability cannot be overstated,” said Feldblum, who is also the daughter of a Holocaust survivor. “All of us have the responsibility to create a society in which we feel safe to come out.”

“There is so much stigma, fear, and misunderstanding about mental disabilities, no one feels comfortable about coming out,” said Iyer, whose parents initially were upset when she came out as bipolar and a person with a psychiatric disability. There was a “cultural component,” they wanted her to “keep it quiet,” she didn’t need to talk about it.

Iyer was perplexed. “Personally, I didn’t know it was effecting me until I didn’t want to accept it,” she said. “It felt like a sense of weakness. But that’s a process— to accept.” Now, Iyer asserted, her psychiatric disorder “is part of who I am” and her parents are proud of her and how she uses her coming out for her own recovery and to help others.

“Disability disclosure is a political disclosure,” said Cokley.

Cokley also noted that one of the leaders of the progressive post-World War I group the League of the Physically Handicapped, which sought jobs for the disabled under President Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), was a 19-year-old lesbian named Sara Lasoff, a file clerk. Part of the problem, then and now, said Cokley, “is that vets don’t like seeing themselves as part of the disability community.”

The panelists asked: how do we get people to come out and change the culture when physical and mental disability is so stigmatized? Not only stigmatized, but painful to recount.

Minter, who is from a small town in Texas, spoke movingly about his “horrible coming out,” first as a lesbian before transitioning in 1996. He endured “brutal rejection,” feeling “damned,” losing his faith as well as his community. And while much progress has been made for LGBT rights, there are still kids in the South going through the same thing today, which is why there are such high rates of suicide.

“Trauma is so pervasive in the LGBT community,” Minter said, especially among people who are gender non-conforming. “I’ve had guns pulled on me,” among other traumatic experiences that have “deep, lasting consequences. We’ve got to make space in the LGBT community to make room for that.”

“There is no ‘post’ in PTSD,” said Cokley. “People have active traumatic stress. Not just among soldiers. The number of LGBT people suffering from traumatic stress is huge. But they don’t talk about it.”

Or perhaps they don’t know that PTSD is covered by the ADA and that treatment for diagnosed stress, depression, anxiety and other conditions are often covered by insurance. If there are problems on the job, the EEOC handles it.

But there is a quiet urgency to the problem of PTSD in the LGBT community. People with “AIDS survivor’s guilt” are aging and in some cases being forced back into the closet because of homophobic senior facilities. And little attention has been brought to PTSD among LGBT veterans.

In June 2010, six months before President Obama repealed the military’s anti-gay “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, Admiral Mike Mullen, chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, appeared at a town hall at USC appealing to the Los Angeles community to hire veterans returning from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and offer support and jobs to military families. He also implored the community to be sensitive to the fact that the vets might be suffering from PTSD.

Mullen was specifically asked at USC about whether gay service members would receive help for PTSD. After all, LGBT soldiers serving in silence were wounded and saw their friends die in combat, just like straight soldiers. Additionally, because of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT), they were hazed, harassed, sexually assaulted, prohibited from writing home to their partners and couldn’t talk to a pastor or counselor, who were obligated to turn them in for being gay—stresses not faced by their straight comrades.

In fact, a 2013 University of Michigan study reported that LGB soldiers were nearly 15 percent more likely to attempt suicide, compared to 0.0003 percent for the entire veteran community reported in another study. LGB soldiers were also twice as likely to develop alcohol problems and five times as likely to suffer symptoms of PTSD. Moreover, nearly 70 percent of the LGB soldiers surveyed said that constantly trying to conceal their sexual orientation contributed to their current PTSD. Presumably, anxiety has dropped with the repeal of DADT and a new policy allowing transgender service members to serve openly that went into effect July 1.

But suicide is not just a risk for LGBT vets. A 2012 Harvard study found PTSD among LGB youth in their 20s. “We found that differences in PTSD by sexual orientation already exist by age 22. This is a critical point at which young adults are trying to finish college, establish careers, get jobs, maintain relationships, and establish a family,” said lead author Andrea Roberts, research associate in HSPH’s Department of Society, Human Development, and Health.

And a February 2016 study at Northwestern University found it doesn’t "Get Better" for some bullied LGBT youth. “Discrimination, harassment and assault of LGBT youths is still very much a problem for about a third of adolescents,” a press release said. “What’s more, it’s often very severe, ongoing and leads to lasting mental health problems such as major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).”

“With bullying, I think people often assume ‘that’s just kids teasing kids,’ and that’s not true,” said Brian Mustanski, an associate professor in medical social sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and director of the new Northwestern Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. “If these incidents, which might include physical and sexual assaults, weren’t happening in schools, people would be calling the police. These are criminal offenses.”

In California, working to keep kids mentally health is of common interest to LGBT and Disability advocates. Equality California has teamed up with the suicide prevention organization The Trevor Project to sponsor AB 2246: Suicide Prevention Policies in Schools, authored by Assemblymember Patrick O’Donnell (D-Long Beach). The bill cites CDC data saying suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people aged 10-24 and LGBT youth are up to four times more likely to attempt suicide than their non-LGBT peers. The bill is supported by Disability Rights California.

“This bill requires schools to actively work toward preventing youth suicide, and identifies specific high-risk groups of young people to ensure those students are not ignored,” said Jo Michael, legislative manager for Equality California. “Those groups include both LGBT youth and youth with disabilities, so the support from organizations that advocate for people with disabilities reflects a goal of the bill.”

AB 2246 might be a good prevention measure but if it passes and is signed into law, it’s only available in California. LGBT and disability rights advocates must strategize soon on how to fix the ADA to make it stronger and more inclusive, as well as educate LGBT people with PTSD and other disabilities on how to access help before the political climate turns any darker and the ADA is revoked or nibbled away by conservative courts. Work productivity and lives really do count on it.

In fact, Mark Bromley of the Council for Global Equality told a Point Foundation conference in Washington DC Thursday that homophobia was directly responsible for a one-percent drop in GDP in India. That’s $19 billion.

Perhaps they might want to learn how to dance while disabled.

This article was originally posted on EQCA POV at the Equality California blog.