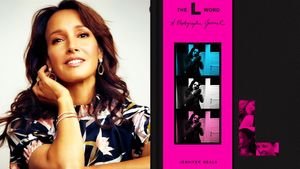

I met Dr. Kopano Mmalane and nurse Nicola Keletso Sarameng at the International Conference on AIDS (#AIDS2018) in Amsterdam in July. The doctor and nurse team work in the Ghanzi (Gantsi is the Batswanan pronunciation) province of Botswana where they primarily treat the San people. It's a remote part of what most people already consider a remote part of the world, but Botswana is actually the seat of commerce between many other African nations—notably South Africa and Zimbabwe—even though it’s landlocked, and as Mmalane notes, “Our one river is the only river that runs inland and dries up in the middle of the [Kalahari] desert.”

There is currently a very high spike in transmission rates among the San people in Ghanzi and they speak an entirely different language than Setswana or English—the two most common languages spoken in Botswana.

A 2017 United Nations’ Fund Report documented Ghanzi as having the highest primary school dropout rate in Botswana. But even for students who stay in school, comprehensive sexuality education is not offered in the classroom. Unlike the rest of the country where Mmalane says they start sexual education in the third grade "we have to, " she says.

As a result, young people are not well equipped to protect themselves against disease and unintended pregnancies. Less than half of young people have comprehensive knowledge about HIV, and less than half of teen girls know at least three methods of contraception, according to a survey published in 2013.

The Weekend Report said earlier this year, “HIV/AIDS which affects poor families in the society,” contributing the article suggests to Botswana having one of the lowest lifespans in the world, “55 years on average.”

This is the backdrop that Dr. Mmalane and Nurse Sarameng work against.

Sarameng describes the process as involving a translator by her side—“I need to get a patient history”—and the only way is by asking them. At the moment Sarameng is the one who tests patients for HIV and then later diagnosis. “After diagnosis you then, you can refer them to the doctor or the nurses who are trained in ARTs.”

Dr. Mmalane was also working in Ghanze when they met— “I was doing the infectious disease counseling, treatment and everything. I was a prescriber for ARTs.”

Mmalane also did the follow up and counseling, Mmalane notes that Sarameng does some of the pretesting and post test counseling. By the time they see Mmalane “I am reinforcing and trying to make sure that they understand and monitor their adherence."

Mmalane says this is difficult among the San as they have some of the lowest literacy rates. Unemployment and alcohol abuse are also very high.

Both women speak about the San with some reverence and note that they are the original people of the southern part of South Africa. "Basarwa is what we Batswana refer to them. And then there was that derogatory term that used to be used which was ‘bushman'."

Mmalane and Sarameng were sent to the region to treat and contain the HIV transmissions—Mmalane says they were embraced by the tribe and that they are a loving people “All these people…they love too much…We’ve got tourist coming through their town, we’ve got people from other tribes coming through their town, and I think that’s how they ended up with the virus now.”

Both women say it’s virtually impossible to have grown up in Botswana and not a had a personal story about HIV—at one point the nation had the highest growing HIV transmissions in the world “When I was young, in Botswana 33 percent of the population had HIV—and this was when I was 13, one out of every 3 people was infected with HIV.”

Mmalane and Sarameng feel they are returning home armed with knowledge and the know-how to help organize in their communities and country “to connect the dots for people—especially women—so they understand what HIV is and how to treat it and more importantly,” Mmalane begins, “Prevent it,” concludes Sarameng.

Photo above from left to right: Nicola Keletso Sarameng and Dr. Kopano Mmalane, Friday, July 27th, 2018, Amsterdam.