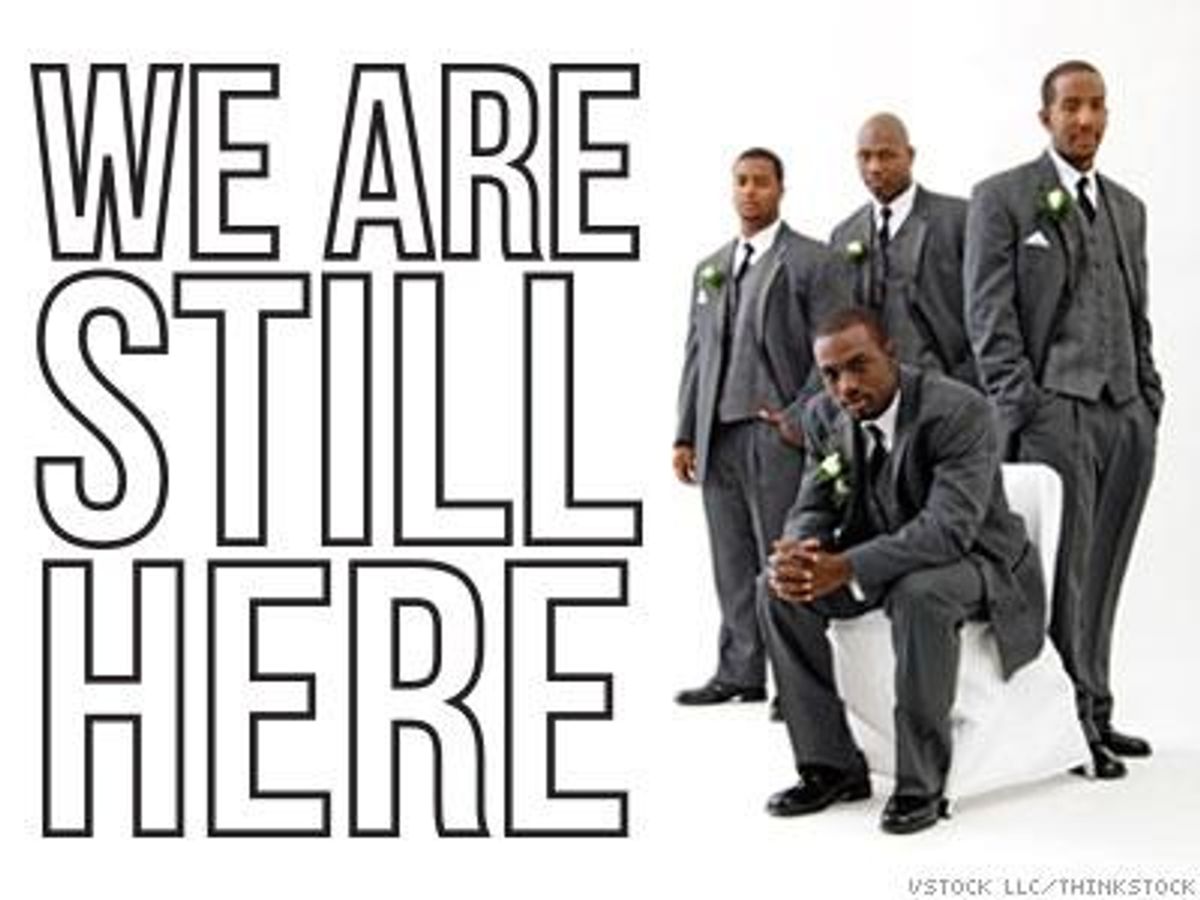

“The black gay male experience is profoundly alienating,” says Charles Stephens in front of a packed audience. The founder of the Counter Narrative Project was at the 18th Annual United States Conference on AIDS and once again trying to explain what it’s truly like — as opposed to how the media portrays it — to be black and gay and HIV-positive.

Later, Stephens elaborates, telling HIV Plus, “As black gay men, more often than not, we are denied a history, denied a culture, and often represented in the most narrow and simplistic forms. We are robbed of our lovely complexity far too often in mainstream culture, and that is in itself a form of violence. To strip someone of their complexity is to strip them of their humanity.”

While LGBT folks celebrate the newfound acceptance they feel with the progress of marriage equality, others aren’t experiencing the same euphoria. Several of the remaining anti–marriage equality holdouts are states in the Deep South, where many black LGBT people still find themselves ostracized by both their spiritual communities and biological families.

Even when they couldn’t rely on the government or society as a whole, black folks had always been able to count on their churches and their families. Leo Moore, MD, an internal medicine resident at the Yale University School of Medicine, spoke at the conference about the pain black gay men experience when “our families — our biological families — abandon us.”

Then there’s the broader LGBT population: “Imagine being a black gay man and coming ‘home’ into a place where you assume that you will be accepted,” Stephens says, and instead, you’re left “enduring deliberate marginalization, silencing, and dismissal. We think about these spaces — Castro, Chelsea, Midtown Atlanta — as being revolutionary and almost utopian. But we forget, for many black gay men, particularly in the ’70s and early ’80s, the racism they experienced, being denied entry into clubs and bars, for example, [and] the minimization of black gay art and literature.”

Charles Stephens, founder of the Counter Narrative Project (right)

Charles Stephens, founder of the Counter Narrative Project (right)

Although things have gotten better through the years, Stephens acknowledges, “I’m also very aware of the racism that exists today within LGBT institutions. It’s a conversation we must be courageous enough to keep having.”

The alienation many black gay men feel after being rejected by multiple communities often leaves them with only each other to rely on — especially if they also have HIV.

Keith Green, a well-known spoken word artist, HIV activist, and former director of federal affairs for the AIDS Foundation of Chicago, echoes that sentiment: “This is who we are. These are our own lives we are saving.”

That oft-repeated phrase — “saving ourselves” — is used by black gay men involved in HIV work as well as part of a new annual Tennessee-based symposium dedicated to bringing leaders in various disciplines together to address the health and wellness of black LGBT people living in the South.

It is both this need for self-reliance and the feeling of running out of time that leads activists like Stephens to talk about the importance of gay black men remembering “our legacy” around HIV and AIDS.

“Our stories matter,” Stephens explains. “We can’t just leave it up to white gay men to tell the story of the ’80s, we must put forth our own narratives. One of the worst things AIDS took from us, as black gay men, has been our stories. Which is why we must keep telling them and keep remembering them. Where there is memory there is resilience.”

Stephens calls passing down that history to young gay black men critical “proof we existed,” and he sees it as necessary for them to “know that they not only have a community behind them, but a culture and a history.”

Green puts it succinctly: “We are racing against time and AIDS to avoid becoming a people that once was.”

Aquarius Gilmer, National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS (below)

Aquarius Gilmer of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS and Stephens agree that black gay organizations — and those who work in them at any level — need to do succession planning now. “There is often high turnover among frontline staff in HIV/AIDS work,” Stephens says. “And with each new staff transition, we lose access to community members and key partnerships. This, I think, perpetuates the kind of destabilization that happens in our communities.”

Aquarius Gilmer of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS and Stephens agree that black gay organizations — and those who work in them at any level — need to do succession planning now. “There is often high turnover among frontline staff in HIV/AIDS work,” Stephens says. “And with each new staff transition, we lose access to community members and key partnerships. This, I think, perpetuates the kind of destabilization that happens in our communities.”

There was a time when all gay men talked this way, a bit too aware of their own mortality. A time when middle-aged men stepped into community elder roles because the generation ahead of them was just…gone. Back then the entire gay community was haunted by ghosts of hundreds of lost friends and lovers, and individual gay men were torn between living it up while they could and trying to quickly archive their generation’s lives and accomplishments before they too were gone, always with the specter of death around the corner. In the darkest moments it seemed almost possible that all gay men would disappear into that sweet night.

Though gay and bi men are getting HIV at increasing rates still, for thousands of white, middle-class gay men, those dark days are long gone. Pharmaceutical advancements and adoption of some prevention strategies (better access to health care, testing, condoms) has given those gay men a new lease on life. For them, HIV is a manageable chronic condition. But for gay and bi men of color, the epidemic is far from gone — and the specter of death still haunts the lives of far too many black men.

According to a recent study from Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, the incidence of HIV is so high that a black gay man becoming sexually active at the age of 18 today has a 60 percent chance of being HIV-positive by the age of 30. At the current rate of infection, one in four black gay men will become HIV-positive by the time they are 25.

The study cited “lack of health insurance and solely having sexual partners from the black community” as key factors, along with unemployment and incarceration.

Not only are African-American gay men and transgender individuals more likely to have HIV then their white counterparts, they are also less likely to know it (only 54 percent of black gay and bisexual men knew of their infection, compared with 86 percent of white gay and bisexual men). They are less likely to receive appropriate medical care and (partly as a result) are more likely to die from AIDS complications.

Blacks accounted for 56 percent of all deaths due to AIDS-related causes in 2009, and their survival time after diagnosis is lower on average than that of any other racial or ethnic group, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2013 HIV Surveillance Report. What’s behind the high rates for gay black men? Some of it has to do with the same socioeconomic forces that lead to the high rates in the southern United States, but, as HIV Plus reported last year, black gay men are also more likely to have sex with other black gay men. Dating within a smaller subset of any population increases the likelihood of one person’s STI being shared with all members of the intertwined group.

While nearly half of all HIV-positive African-American men who have sex with men are unaware of their infection, Jacory isn’t one of them. The 26-year-old gay man was featured on the Our America With Lisa Ling special “Black America’s Silent Epidemic.” He knew he was positive, but he hadn’t started treatment. He didn’t have health insurance, but he also admitted to having a fatalistic attitude, certain that his status would doom him to a poor health outcome. Why bother having a doctor confirm what he already knew? He imagined he wouldn’t live past 35 and would never reach his goal of becoming a fashion designer.

When he finally made it — on camera — to a medical provider, he was given what seemed to be bad news: His CD4 cell count had dropped significantly. And yet Jacory left the medical clinic smiling. For the first time, he understood that with medication and lifestyle changes he could actually reclaim his life. He finally felt empowered to take control of his health. Jacory isn’t alone, and his story touched a chord with black America — at least those who watched the Ling special.

HIV workers agree it’s that kind of basic HIV education that needs to reach the thousands of Americans who still believe HIV is a death sentence and think treatment involves swallowing 30 pills a day. Including Jacory’s story in Our America was certainly laudable — the whole special was — but it may be part of the problem. Black gay men rarely make the news except as connected to HIV statistics.

“Organizations must be willing to know and imagine black gay men beyond HIV,” Stephens said in a statement issued for National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day in September. “Black gay men are not merely the sum total of a series of horrible health outcomes. Black gay men are not merely a risk group, representative of the pervasive MSM category, but a people, with a history and a culture, a rich legacy of activism that has meant both our survival and secured our future.” Stephens argues that the “black gay identity [is] a unique social location, point of political struggle, and space of joy” and he hopes that Counter Narrative can “amplify the voices of black gay men” by bringing visibility to broader issues affecting the population, including poverty, criminalization, and lack of housing. “We believe that visibility is necessary for cultural change, and cultural change is necessary for social change.”

Rashida Richardson of the Center for HIV Law and Policy agrees that HIV criminalization laws have an inordinately high impact on black gay and bi men. In a recent webinar, “We Are Here: Toward an Advocacy Agenda for Black Gay Men in the South,” Richardson explains this is because HIV criminalization lies at the intersection of forces that affect black gay men disproportionately: incarceration and high rates of HIV infection.

“One in three black men will be incarcerated during the course of their lives,” Richardson says. “Gay and transgender youth who end up in the justice system are at risk of being labeled sex offenders, regardless of what crime they have actually committed. Queer people of color are more likely to be targeted by police for stop-and-frisks, which can lead to HIV criminalization charges” if, for example, the officer comes in contact with an HIV-positive person’s saliva. The complexity of the issues facing gay and bi black men — and how they intersect with HIV rates among African-Americans — may be one of the reasons activists like Stephens and Gilmer see the need for black gay men to collaborate with other disenfranchised populations to stop HIV’s death grip on their communities.

At the AIDS conference, Gilmer publicly apologized, on behalf of black gay men, for helping render transgender women and men invisible, insisting “we must include transgender issues in the black gay men agenda.”

Later Gilmer spoke in the “We Are Here” webinar about the need for black gay men to fight for justice alongside other underprivileged groups rather than becoming involved in what he calls “privileged movements.” For example, Gilmer points to the fact that marriage equality has been the primary focus of the larger LGBT community but “gay black youth believe that HIV should be the central issue.” (Presented by the HIV Prevention Justice Alliance and the Counter Narrative Project, the webinar focused on HIV criminalization and incarceration, mental health and trauma, intersectionality, social justice, engaging faith communities, access and barriers to health care, and the role of culture in community engagement, mobilization, and building power. You can watch the entire 90-minute video here.)

Building coalitions can be difficult, even with seemingly natural allies like black women with HIV. As Ling reports, there’s still a widespread belief among African-American women that HIV is contracted via sex with their male partner who has gotten it from another man. This narrative, says Moore, paints black gay and bisexual men as “the enemy” who are “single-handedly responsible for HIV in black women.” Which in turn sets up what Gilmer calls “a fight for who is more devalued — black women or black gay men.”

Although studies indicate the narrative isn’t true, black gay men are frequently forced to “carry the burden of HIV,” Moore adds, because they often become the focus of HIV stigma and fear.

Fear played a role in Gilmer’s own coming-out story. When he was first diagnosed, he was working in Mozambique assessing community-based, in-home HIV care. Although he was working in the HIV field and knew he was likely positive, Gilmer admits he avoided seeking medical attention. Finally he reached out to a friend, but even then he couldn’t admit the advice he sought was for himself. Instead, Gilmer said he had a “friend” who wouldn’t see a doctor because he was afraid. His friend said, “Tell your friend, HIV won’t kill him, but fear will.”

“It is fear,” Gilmer knows now, “that paralyzes many of us.” Whether it is fear of losing your church or family, or of what might come with treating the disease, he says, “it’s the fear that anchors the shame and stigma; [the feeling that] if I speak and admit this, then my world as I knew it will crumble. Now, realizing that the possibility of life is on the other side of taking a pill? The other side of a doctor’s appointment?”

Despite all the hurdles facing black, poz gay men, activists like Gilmer and Stephens remain cautiously optimistic. “Given the opportunity,” Gilmer says, black gay men “could help lead this country…because we are so much more than HIV.”

Stephens happily acknowledges the “great work happening in the scientific and policy realms,” but adds, “I would merely offer that we should continue to work to strengthen our institutions, sustain our culture, and really invest in our communities.”

It is in investing in the “proliferating black gay media, art, community institutions, and other innovative forms of community development” that, Counter Narrative maintains, black gay men will find the care they need to overcome HIV. “Linking black gay men to culture is linking black gay men to care.”

And for a young gay black man reading this article? “I would want him to know that he has a community behind him,” Stephens says. “He has a history, a culture, and a future. As black gay men, as fearlessly as we look back at our past, the joy and the trauma, we have to be just as willing to consider the future.”

Charles Stephens, founder of the Counter Narrative Project (right)

Charles Stephens, founder of the Counter Narrative Project (right) Aquarius Gilmer of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS and Stephens agree that black gay organizations — and those who work in them at any level — need to do succession planning now. “There is often high turnover among frontline staff in HIV/AIDS work,” Stephens says. “And with each new staff transition, we lose access to community members and key partnerships. This, I think, perpetuates the kind of destabilization that happens in our communities.”

Aquarius Gilmer of the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS and Stephens agree that black gay organizations — and those who work in them at any level — need to do succession planning now. “There is often high turnover among frontline staff in HIV/AIDS work,” Stephens says. “And with each new staff transition, we lose access to community members and key partnerships. This, I think, perpetuates the kind of destabilization that happens in our communities.”